In a truly spectacular case of bizarre reasoning, multiple people have posted on twitter variations of a claim, made, perhaps first, by Nicholas Kristof in his New York Times column:

there was no controversy about the arrival of this eclipse; we all accepted the scientific consensus about its timing and swarmed to the best viewpoints. So why is there such resistance to the similar scientific consensus about other foretold events — such as climate change?

Which is, well, odd.

We have a certain popular mythology that ancient, or more simply non-modern peoples, were terrified at eclipses, worried that these were portents of the apocalypse, of famines and natural disasters. We are better than they are, because we know what causes them and our scientists can predict them, so we enjoy the experience, while they surely, primitive as they were, cowered in fear.

And that may be true for our prehistoric ancestors. But the ancient Chinese, the Babylonians, the Greeks, and so on, had worked this out reasonably reliably. (See NASA’s website, for instance.) And, yes, they knew when eclipses would occur even at a time when they believed that, to cure a disease, one should bleed the patient. Now, did peasants know this? The Vikings? How well was this knowledge preserved in the monasteries of the early Middle Ages? I couldn’t say.

But none of this proves anything about climate change. An eclipse is a specific event, occurring in a cyclic pattern, which can be predicted with precision. Climate change is no such animal — there are models which attempt to estimate future climate within ranges, but there are multiple variables, not a simple, direct, and immediately predictable relationship between the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the temperature.

Now, some people will also claim that climate scientists have predicted the recent series of warmer temperatures, that is, that they have predicted events that have occurred in the past, and that this “proves” that they are right; but what they’ve really done is developed models by fitting their equations to this past data; the broader principles of climate change models as a determination of future climate cannot be proven until we are, well, in the future — and the amount of time that’s passed since climate scientists first developed these models is, so far as I understand, insufficient to claim that they have “proven” anything yet. (Yes, this is, perhaps clumsily stated, a principle from one of my actuarial exams — you cannot “prove” your conclusions simply by using your data to build a model; you then have to go out and gather more data and demonstrate that the model works for the new data.) And, look, I’m not interested, within the confines of these few words, in arguing the broader point of what climate scientists have to say, and that’s completely not the point of this post, but it’s in the nature of climate models and prediction (as is the same with, say, economic models, or any other sort of similar construct) that they can only offer ranges and approximations and estimates, and the precision of a solar eclipse timing calendar offers us no meaningful comparison to climate science.

An eclipse is an interesting event to watch. Here in northern Illinois, we watched for the brief parting of the clouds that occurred just before the time of maximum coverage, then went out and put our glasses on and, sure enough, the sun was just a sliver. (Was the sky demonstratably darker as well? It’s hard to say how much was due to the clouding up vs. the eclipse.) In the path of totality, it sounds like it was great fun to watch, though claims like Bill Nye’s are a bit over the top, when he said,

I hope this brief period reminds us all that we share a common origin among the stars and that we are all citizens of the same planet.

Um, no — I don’t think anyone reported feeling a greater sense of unity. If anything, there was a clear divide, between those within the path of totality, whether they lived there or had the means and interest to travel there, and those who weren’t. (Nye also lauded “modern astronomers” and Galileo and Copernicus, without recognizing that eclipse prediction is not a marvel of modern science but speaks to the scientific inquiries of much earlier ancestors.)

What people did seem to feel is more of an “awe at creation” sort of thing. And, in fact, there is something special about eclipses on earth. As told by EarthSky.org,

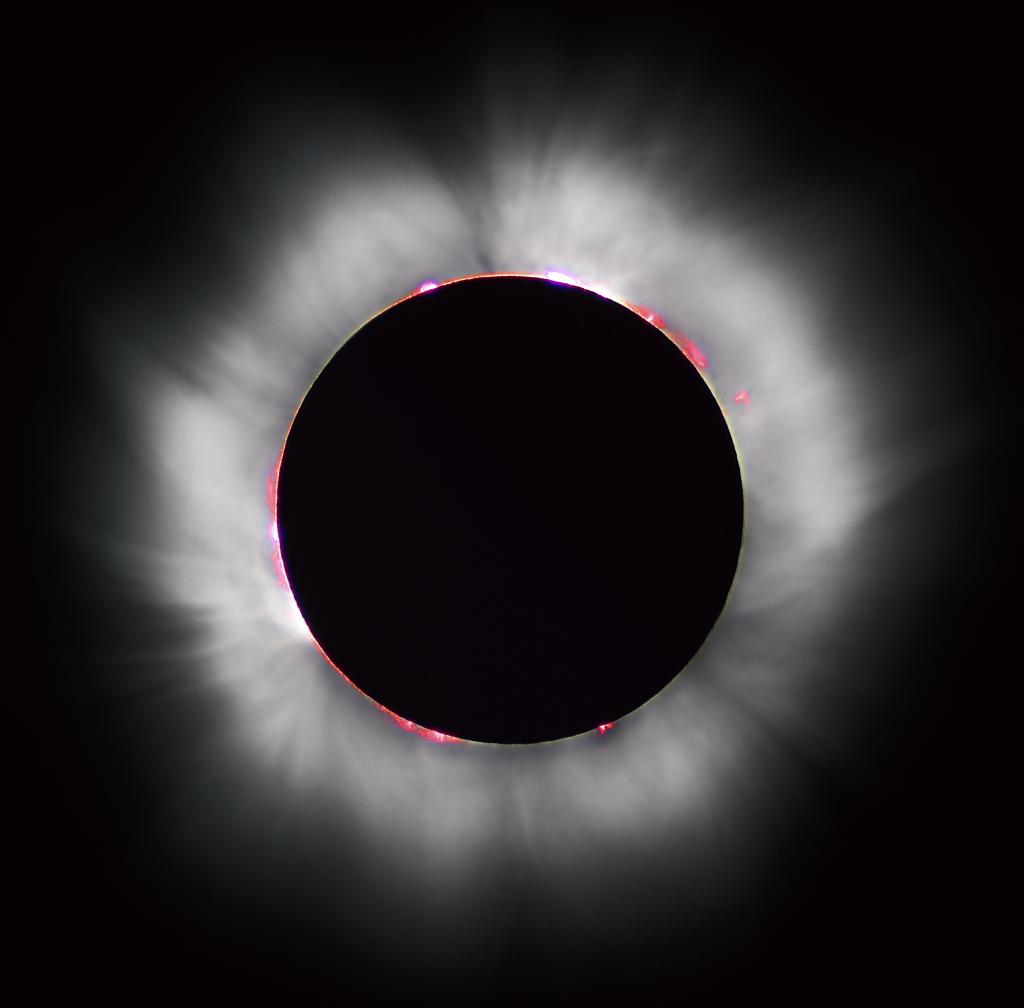

the main reason [why our eclipses are so special, even though eclipses in general occur elsewhere in the solar system] is that the sun and moon appear roughly the same size in the sky, allowing particularly impressive total solar eclipses. During totality of a solar eclipse, the silhouette of the moon leaves a gaping “black hole” in the sky, surrounded by the ghostly glow of the sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona.

This fortuitous circumstance happens because although the moon’s diameter is about 400 times smaller than the sun’s, it also is about 400 times closer. That makes the sun and moon to appear roughly the same size in the sky, about a half-degree. If the moon were 10% closer, as it was about a billion years ago, it would always appear appreciatively larger than the sun, and some of the magic of today’s total solar eclipses would be lost.

If the moon were 10% farther away, as it will be roughly a billion years in the future, it would appear too small to completely cover the sun’s disk, and we would never experience a total solar eclipse.

Which isn’t a matter of marveling at the power of scientists, so much as the extraordinariness of life on earth.

So, bottom line: does the eclipse “prove” climate change directly? No.

Does it prove climate change indirectly, by establishing the collective wisdom of science and scientists, as a single unified group? also no.

And, as always, readers, I invite you to share your experiences, especially if you were in the path of totality.

Image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eclipse#/media/File:Solar_eclipse_1999_4_NR.jpg; By I, Luc Viatour, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1107408