Because I finally found out how to access survey data on church attendance! This is the General Social Survey, run at the University of Chicago, funded by the National Science Foundation, with data going back to 1972. It tracks such questions as “do you believe in God?” or “what is your religious preference?”

And it asks about church attendance.

Now, I’ve seen statistics about church attendance before, largely in the form of a Gallup poll that asks, have you attended church in the last seven days. And there’s always the complaint that people who think of themselves as usually going to church, but didn’t go the Sunday prior to the pollster’s call, lie and say they did, so that the “yes” replies are overstated. But the General Social Survey isn’t black-and-white, but offers a fine gradation of responses:

- more than once a week

- every week

- nearly every week

- 2 or 3 times a month

- every month

- a couple times a year

- once a year

- less than once a year

- never,

along with splits by region, age, education, and so on,

and I thought, “awesome! I can finally see if my hunch is right, that the drop-off in religious practice has been that people that, some decades ago, would have considered them Christian, even if they barely go to church and aren’t sure they believe anything other than Jesus Was a Nice Guy and All Dogs Go To Heaven, now have decided that they don’t need to bother with it.”

And I looked at the charts. And I exported the data, and I sliced and I diced, and — well, I didn’t find that perfect insight that’s going to amaze everyone who reads it.

But I’ll share with you what I learned anyway.

Let’s start with some basic tables. It seems to me that the most useful measure of regular religious practice is the percent of respondents who replied that they attend some sort of service on a monthly basis. Yes, within that group, there’s a difference between those who attend weekly and those who don’t, and, for families anyway, there are increasing number of activities conflicting with weekly attendance — sporting events, extracurricular activities, etc. It’s challenging enough for Catholics who typically have Saturday evening masses available, or even Sunday nights, but for a Protestant who has one worship service or maybe two to choose from? Good luck with that one! But monthly attendance seems to be a basic marker of frequent enough attendance to have some connectedness with one’s church, so I put together some charts on this basis.

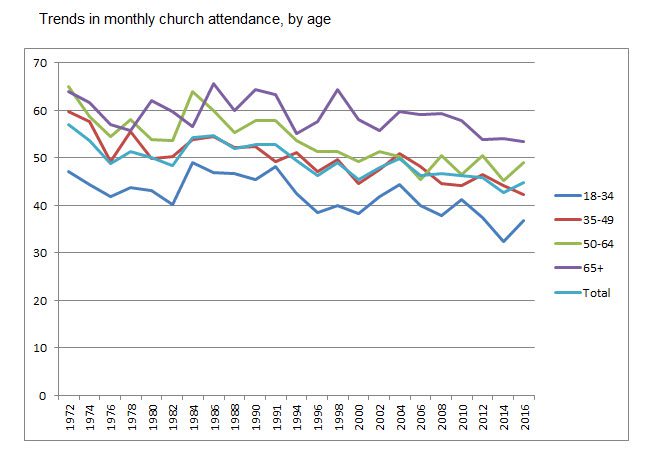

Here’s monthly attendance by age.

Not surprisingly, the 18 – 34s are the least likely to attend, and there’s been a definite drop, although there’s also been some bouncing around, higher in the 80s, then a drop and an early 00s recovery, and now a steeper drop. In fact, there’s a lot of bouncing around, which would seem to suggest that these are small sample sizes, though I couldn’t find details on that. And, by the way, these are simple excel charts, and I really stink at formatting them nicely, but the advantage for you is that I don’t play around with them and the Y axis starts at 0.

Slicing and dicing differently, I took three-period averages because I didn’t like the data, then looked at the relative changes over time.

So what’s interesting here is that, for all that young adults attend church less frequently than their elders, the relative drop-off since 1974 (which is, again, averaged), is pretty nearly the same for all ages except the 65+ group, but the patterns are different, as the 18 – 34s stayed steady in the earlier part of this period, then “caught up” afterwards.

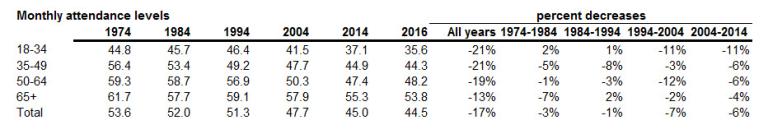

Here’s another chart, monthly attendance by region.

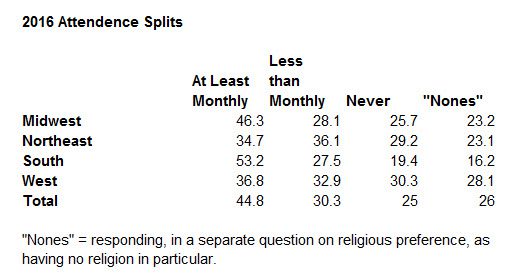

So, yes, the Northeast and the West have always been the least church-attending regions. At present, here’s a split by region of overall patterns:

Some other data points:

Women attend church at consistently higher rates than men; in 2016, these rates were 48.8% of women attending monthly vs. 39.4% of men. That ratio has stayed fairly constant over the time period since 1974. What has changed is that in the past, women were even more likely than men to attend on a weekly or near-weekly basis, as much as 50% more often than men, in the 1980s, and women’s attendance has dropped more than men’s. From 1985 to 2016, women’s weekly attendance dropped by 28% to 27.5% of women, and men’s weekly attendance dropped by 14% to 22.3% of men.

The relatively more educated (some college or more) and the relatively less educated (drop-outs) attend more often than those in the middle, with only a high school diploma, with monthly attendance rates of 46.9%, 41.8%, and 48.3%, respectively, again, on my smoothed basis.

Those who describe themselves as middle class are more likely to attend than those who consider themselves as working class — 47.1% vs. 42.8% based on the smoothed monthly rates. (They also have classifications of “lower class” and “upper class” but these rates bounce around a great deal and I don’t trust the data, since it’s a matter of self-identification, and I imagine that these two groups are very small and the portion of the population willing to identify themselves as such changes over time.)

And here are two more data items from other sources:

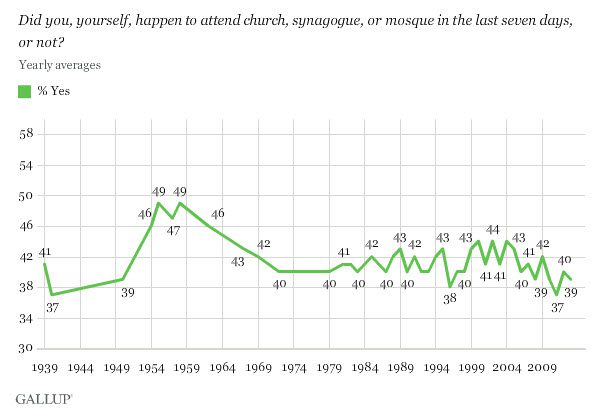

First, a Gallup poll on church attendance, showing that the 50s were an unusually religious time period, and the 40s weren’t, despite the image of everyone praying on D-Day. Again, this poll likely includes semi-regular attenders, but it still captures general trends, though it could artificially sink at some point if the semi-regulars no longer see a need to feel better about themselves or look better to the pollster.

See also an article about postwar religion in America, “Why 1940s America wasn’t as religious as you think — the rise and fall of American religion,” which reports that the 50s were a boom period for religion, sometimes called the “Third Great Awakening.”

And, in today’s twitter feed, a report from Pew on Christmas practices, which reports that only 51% of Americans plan to attend services on Christmas or Christmas Eve. This is a surprisingly small number to me, given that 75% of Americans report that they attend religious services to at least some degree (that is, not “never”). To be sure, “religious services” can take the form of the temple or mosque, but the percent of Jews, Muslims, and “other” don’t account for this gap; according to the GSS, it’s 6%. Which must mean that a fair number of the sporadic churchgoers are counting Great-Aunt Mary’s funeral, or their niece’s baptism, but aren’t observing the traditional “Christmas and Easter.”

So what’s next? To begin with, should we reasonably expect church attendance patterns to stay the same when society itself has changed?

Society in 2017 is not a replica of the society of 1974. And by that I don’t mean that there have been social changes in the meantime, but simply that demographically the people of America in 2017 are not simply the next generation taking the place of their elders. 14% of the population is foreign-born; a further 12% are the children of immigrants. Of the native-born population, Mormons, black Protestants, Evangelical Protestants, and Catholics have the highest family size; mainline Protestants, atheists and agnostics have the smallest families. (This is based on “completed fertility,” that is, by polling women ages 40 – 59, past their prime childbearing years, so it won’t capture trends in recent years.) This latter difference would suggest that church attendance should rise over time; that it’s not is because a fair portion of those raised with a faith, leave that faith — and, beside that, I couldn’t fine any statistics on fertility correlated with degree of religiosity vs. simple religious identification.

So we can’t simply expect that levels of religious practice, or particular religions being practiced, will stay constant by being passed on from parents to children. What matters instead is what’s going on in society as a whole, to the extent that there is such a thing as “society as a whole.”

Which means that I’m asking myself, is there a tipping point?

The infrequent attenders are, if you will, a swing group. If the overall culture is a “Christian” culture in which religion is the norm, they’ll see themselves as part of that group. If irreligiosity becomes the new norm, one would expect that they’ll swing in that direction. And American culture has unmistakably shifted. The “civic religion” that was once a loose version of Christianity, has now taken the form of celebration of “diversity” and “multiculturalism” which is, if not in conflict with a Christian culture, than certainly nothing that reinforces it. The whole Roy Moore spectacle certainly creates an image of Christianity in conflict with non-Christians. To the extent that “diversity” has now become acceptance and even celebration of same-sex relationships, and a rejection of anything that hints at “intolerance” (except, of course, that one may be as intolerant of traditional Christianity and Republicans as one likes), it pulls this group further away. It might be a trivial example, but it seems to me that not long ago, comics used church attendance as a set-up for a joke; now the “shared cultural activity” that takes place on Sunday morning is brunch.

And people’s perceptions of what the culture at large says, matter. Yes, Christians like to say they’re “countercultural,” but in reality it is no fun to be in the minority, and to feel that minority status, and a perception that church-goers are in the minority will serve to encourage on-the-fence adults to identify otherwise.

And none of this has to do with the claims that it is our society’s wealth and education that means that we don’t “need” religion as a source of comfort in times of hardship. After all, again, it is the more educated, better off, who are more likely to be churchgoing. And one reads plenty often that we in America are taking the same path to secularism as Europe did, just a bit later — but, even if the end result may be the same (and we don’t know that yet), their path doesn’t seem to have been our path. Their secularism is paired with, in most countries, an official or semi-official State or societal observance of Christianity. In Bavaria, schools have crucifixes, and children go to church at the beginning and end of the school year. They have, for the most part, not had our insistent culture of “diversity.” The reasons for their rejection of or disinterest in Christianity surely lie elsewhere, say, in the disillusionment of the World Wars, or the impact of the State church becoming watered-down, or the legacy of secularism politically — e.g., in France.

And, again, one would like to say that we’ll lose the “cultural Christians” and it’s no big deal because our core of churchgoers will stick around. But it seems likely that there’s a tipping point in which we lose those churchgoers, too.

Image: Church of St. Luke and the Epiphany, Philadelphia (public domain via Wikipedia)