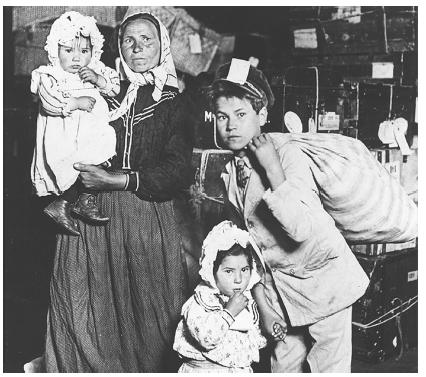

The conventional wisdom on immigration from a place like El Salvador is clear: the country is dependent on those immigrants because they both relieved the pressure of needing to support these people, at home, and because they provide remittances, to the tune of billions of dollars, from the countries in which they now live and work.

And at the same time, we’re told, these people benefit the receiving countries. They’re ambitious and work hard, and are better able to put their talents, such as they are, to good use in these healthier economies. It’s a win-win.

Here are some numbers:

According to a 2013 UNICEF profile of the country, El Salvador, with a total population of 6,340,000, there are 1,463,000 migrants to other countries, nearly all, 1,372,000 to the United States. Pew reports that this figure increased to 1,420,000 by 2015. This means that about 20% of all Salvadorans live outside the country. And the country has come to depend on the money they send to their families back home, about $4.5 billion annually, or 17.1% of their economy.

That doesn’t mean that the population of the country has declined by 20%, to be sure, as the fertility rate has only in the last several years dropped to below-replacement levels, after being much higher than replacement-level until the 2000s. So, all other things being equal, it’s a net positive for the country, right? No loss in population but extra cash coming in from outside.

But consider that we Americans like to think of ourselves as special because our ancestors were, among those in their Old Country cities and villages, the risk-takers, the bold, ambitious, energetic ones, who brought that energy to the United States. Has El Salvador lost the top 20% of its people, measured by the level of ambition, determination, ability to take risks and try new things and succeed?

That’s probably not quantifiable, but in trying to find an answer to that question, I did find a blog post that reported that what has been happening is a true brain drain. This is from the Center for Immigration Studies, which is fairly restrictionist on immigration but diligent about marshalling statistics to document its claims, and it cites a report from the Central Bank of El Salvador to say

based on a survey of immigrants in the U.S., 4 out of 10 emigrants were professionals who met the academic requirements for the majority of companies in El Salvador.

The report shows Salvadoran immigrants send 15 percent of their income back to their home country as remittances for their family. Most of these immigrants, while considered professionals in their home country, work in the service industry in the United States.

Further citing a link which now redirects to ElSalvador.com, the post says

The president of the bank, Oscar Cabrera, noted the Salvadoran economy is not producing enough jobs to absorb the thousands of youth that enter the labor force each year. Cabrera added, “Remittances received from 1980 to 2012 represent 11 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP), but the cost of this migration is 11.8 percent, so that our society is losing with this outflow of professionals.” The bank’s president explained the country could not continue with the loss of skilled workers. There is an opportunity cost, he said – the brain drain reduces productivity, it causes a shortage of skilled labor, and hinders innovation.

As far as Haiti, here’s a dramatic statistic: a webpage dated 2016 reports that 81% of Haiti’s university graduates have left the country. The Nation reports that this is the most severe brain drain in the world. And they’re generally not trying their luck in the United States, but moving to Chile; previously Brazil was popular until its recent economic troubles.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. In Europe, there are ongoing concerns about a brain drain from Eastern European countries, and from the former East Germany. Not long ago, the Economist had an article that, at least in the case of Poland, their overall labor shortage caused by its workers leaving for Germany, the UK, and the like, has been partially mitigated by immigration into Poland from the Ukraine. While these are largely manual workers, perhaps the high level of education in Poland means that loss of university graduates isn’t as worrying; it’s not clear.

So we can pat ourselves on the back for how welcoming we are to sh**hole-originating immigrants, or we can block them, but that’s missing a significant part of the picture of how their departure impacts happening at home.

Image: https://pixabay.com/en/brain-human-anatomy-anatomy-human-1787622/