Yeah, a more conventional blogpost title would be something like, “what you should think about birthright citizenship,” but I think there’s a lot of room for disagreement here, and I’m not going to claim that I have all the right answers. But let’s think about the issue a little bit.

To begin with, there are three separate issues:

- Is citizenship at birth for anyone born in the United States, other than the narrow exception of someone born of two parents present as diplomats with attendant diplomatic immunity, guaranteed by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution?

- Whether or not the above is true, is it appropriate and reasonable to grant citizenship in this manner?

- Are there harms to the country resulting from birthright citizenship, and, if so, are there other remedies besides the removal of this provision?

Let me address these in reverse order:

First, those who oppose birthright citizenship point to two different issues: illegal immigrants and birth tourists. With respect to the former, they cite women who cross to the United States while heavily pregnant, and seem to not simply happen to give birth while living illegally in the United States, just because that’s what happens when young adults migrate and find love, but who aim at having American-born children for the benefits they can confer on parents — especially protection against deportation (which isn’t legally the case, strictly speaking, but de facto this moves them to “not a priority”) and the promise that someday a child can sponsor family members for legal residency. With respect to birth tourists — well, who wouldn’t feel that foreigners coming here on tourist visas and staying to give birth to give those children the benefit of American citizenship are unjustly exploiting loopholes? So far as I’m aware, not even immigration expansionists defend this practice, but only suggest that there is little to no quantifiable actual harm being done, so that it’s not worth attempting to end.

Can we end these practices without actually ending birthright citizenship? The former is part and parcel of the question of whether we can step up our enforcement of illegal immigration: if we increase border enforcement, track visa overstays, mandate E-verify, and enforce prohibitions against under-the-table work, so as to result in fewer illegal immigrants, there will be fewer so-called “anchor babies” in the future. Short of that, Congress could easily enough remove parents as a category of relative which a citizen can sponsor for immigration. As to the latter practice, the problem is narrower but there is no immediately obvious solution, since we can’t pregnancy-test every visa applicant. Maybe there are some solutions around the edges, such as prohibiting the practice of running a birth tourist practice — though I’m not sure how clearly a law could be set out that would prohibit birth tourism without ensnaring, say, an Air B&B host whose customer happens to have been pregnant.

Backing up a bit further: is it right or wrong for a child born while a parent is here on a tourist visa, to receive automatic citizenship? I think most would agree that the answer is “wrong.” Does it do us quantifiable harm? It’s easy to imagine scenarios in which these folks later show up as young adults, with their loyalty elsewhere, but with the aim of, say, studying in the United States without the hassle of a student vias, and with eligibility for student aid, to boot — but since the practice is relatively new, we can hardly quantify it. Does denying such a child, whose ties lie elsewhere, U.S. citizenship, in turn, harm that child? No, not unless you define “harm” especially broadly.

But what about the child born of illegal immigrant parents, who intend to stay and who, in practice, will stay, given the consensus, for better or for worse, that parents of U.S. children are generally not targets for deportation? (Yes, I know, there are periodic reports of such individuals being deported, but the vast majority are not.) On the one hand, in almost all cases, claims that these children would be “stateless” are incorrect, as they would be citizens of their parents’ homeland(s). On the other hand, it’s simply wishful thinking to imagine that if these born-in-America children of illegal immigrants were themselves deemed just as illegally present, they would go away. But if we were developing a policy “from scratch”, we might land on something altogether different, for instance, some sort of conditional citizenship which provides no protection against deportation if a custodial parent is to be deported, but converts to “regular” citizenship at the age of majority if the individual has been more or less continuously resident in the country.

So having said all that, back to the original question: what does the 14th Amendment have to say?

It may not be as simple as that narrow definition in which “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” refers to every circumstance except for diplomats. The Heritage Foundation, among other sources, provides a handy run-down of the relevant historical context.

Based on the legislative history at the time, the 14th Amendment’s framers intended to give citizenship only to those who owed their allegiance to the United States and were subject to its complete jurisdiction, primarily the newly freed slaves, who were lawful permanent residents.

Owing allegiance to the United States and being subject to its complete jurisdiction means being “not subject to any foreign power” and excludes those only temporarily present in the country.

Most legal arguments for universal birthright citizenship point to the Supreme Court’s 1898 decision in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, which challenged the government’s decision to deny re-entry to a U.S.-born child of foreign nationals who were legally present and permanently residing in the United States.

Wong Kim Ark stands only for the narrow proposition that the U.S.-born children of lawful permanent resident aliens are U.S. citizens. It says nothing with respect to the U.S.-born children of illegal or non-permanent resident aliens.

In the famous Slaughter-House cases of 1872, the Supreme Court stated that this qualifying phrase was intended to exclude “children of ministers, consuls, and citizens or subjects of foreign States born within the United States.” This was confirmed in 1884 in another case, Elk vs. Wilkins, when citizenship was denied to an American Indian because he “owed immediate allegiance to” his tribe and not the United States.

Without opining on whether “jurisdiction” means “complete jurisdiction” in the manner in which they interpret it, it seems to me that there is not really a good answer on the question of “did those who wrote, voted on, and initially interpreted the amendment intend to include illegal immigrants and tourists?” because those categories simply did not exist at the time.

There was no concept of an illegal immigrant in 1868. if you wanted to come to the United States, you came. The first restriction of any kind was enacted in 1875, the Page Act which prohibited “individual from Asia who was coming to the United States to be a forced laborer, any Asian woman who would engage in prostitution, and all people considered to be convicts in their own country”; the law had the effect of severely limiting the entry of Chinese women because they were viewed as potential prostitutes. The Immigration Act of 1882 forbade convicts, the insane, and those “likely to become a public charge” from entering the country, but it took quite some time beyond that before there would have been people who would have fit the modern category of “illegal alien.” (Though one wonders what would have happened in the event of a woman, newly arrived on Ellis Island and judged unfit to remain, who gave birth before being sent back. Would mother and child have been sent back? Would no one have even given any thought to fighting for the right of the child to remain because it would have seemed preposterous, and no attention was given to any “citizenship rights” because when there were no immigration restrictions applicable to a (non-Chinese) healthy young adult, there would have been no need to argue over status at birth?)

Likewise, the concept of a “birth tourist” — of someone seeking to take advantage of citizenship rights due to birth — would hardly have been comprehensible at the time.

What would the Supreme Court have meant in 1872 when referencing “citizens or subjects of foreign States born within the United States”? Immigration was plentiful, so there were plenty of individuals who were “citizens or subjects of foreign States,” and it seems unlikely that they meant to encompass everyone who had not renounced their foreign citizenship in this exclusion. To my nonexpert eye, it seems more likely that they might have intended to encompass temporary residents as a general class, but that all manner of temporary residents/visitors in 2018 — expats on business assignments, scholars, students — either wouldn’t have existed, or would have consisted of men who would either be unmarried or would have left their wives at home for years at a time. (Fun fact: in the early 1900s, my great-grandfather came from Greece to seek his fortune, and it took 10 years before he was settled and sent for his wife and children.) Looking at the context that the Heritage Foundation (and, again, similar sources) provides, it seems likely that “birth tourists” and others who are clearly here temporarily would fit into this exception — while they might be “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States in that, had they committed a crime while on our territory, we’d prosecute them, the whole clause is vague enough to suggest that a Supreme Court decision could go either way.

Plus, the amendment is vague as far as timing is concerned: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” “Born” is in the past, but “are” is in the present tense, and tends to suggest that the “subject-ness” has to be more ongoing than would be the case if the amendment stated “all persons who are subject to the jurisdiction of the United States at the time of birth, are citizens.” In fact, the construction suggests that in either the case of citizenship by birth or naturalization, one can lose that citizenship by no longer being “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” — or at least that such citizenship is no longer guaranteed in that case.

But, as much as the Amendment seems to me to have envisioned a distinction between temporary and permanent residents, I don’t see such a distinction between those who are here legally or illegally. Imagine that someone had time-travelled, and said, “hey, what if someday in the future, the country decides to restrict immigration and people cross over illegally anyway? Do you want your amendment to say that their children are citizens, or not?” The amendment drafters may or may not have said, “oh, that’s a good idea, we should be more specific.” But they weren’t.

And ironically, this is where anti-illegal immigration folk who want to wish away this problem become like gun control folk who want to wish away the Second Amendment. “Surely if the drafters had known that someday there would be immigration restrictions, they would have taken that into account” sounds a lot like “surely if the Founding Fathers had known that we’d have not just muskets but semiautomatic rifles, they wouldn’t have permitted them.”

So that’s where I’m at.

If I haven’t lost you already by my overly-long post, what do you think?

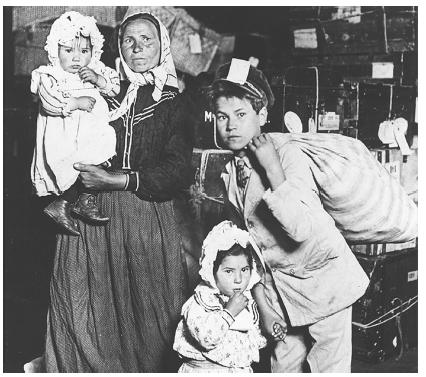

Image: By Lewis W. Hine(Life time: 1874-1940) – Original publication: Photo-studyImmediate source: Brooklyn Museum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51292180. The text which is cropped off says that the worried looks are due to lost luggage, a detail I found interesting since this picture seems to be a standard one exemplifying hardships of new arrival.

We want to know what you think about the upcoming midterm elections. Vote in our poll below!