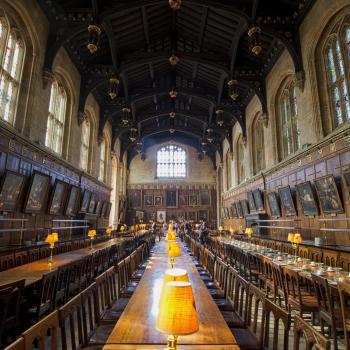

In the Atlantic the other day (well, actually two weeks ago or thereabouts), “Five Ways to Make the Outdoors More Inclusive.”

As a disclaimer, yes, the article is clearly identified as “marketing,” and it’s sponsored by REI, and their objective is not really to “make the outdoors more inclusive” but to market themselves to outdoors enthusiasts as the socially conscious choice for purchasing outdoor gear.

But the author/marketer cites that statistic that 78% of those who visit federal parks are white, though their link is bad, so it’s not possible to determine whether this refers to national parks specifically or all National Parks Service-administered properties, whether it distinguishes between Americans and white European tourists, or whether it includes Hispanic-ethnicity-folk in its definition of “white.” In addition, they report,

African Americans, Latinos, women, and members of the LGBTQ community often report feeling unwelcome or unsafe in outdoor spaces. Moreover, the outdoors industry workforce—which includes everyone from park rangers to retail sales associates—has minimal representation from these groups.

In order to think about these issues, REI / The Atlantic / the marketing group convened a panel for a “brainstorming group” and came up with recommendations, some of which might well be useful, others of which are silly, and yet others could do more harm than good, in furthering the cause of encouraging greater engagement with nature by non-white, non-male non-straight non-native born non-etc. Americans.

Among these:

Increase the degree to which the history of minority groups is documented and memorialized within the park system, both by means of “telling the stories” (e.g., creating museum gallery spaces) of those groups at existing parks as well as creating new “storytelling-driven memorials”. This may or may not be a worthy cause, and might increase the budget of the National Parks Service, but isn’t going to increase the amount of time these groups spend in the outdoors. Consider that the Cesar Chavez National Memorial cited as an example in the article is located on the property of the United Farm Workers headquarters, and only a visitor center and the gravesite are open to the public for this reason. Likewise the new Pullman National Monument was celebrated by civic boosters in Chicago, who even initially hoped it would be declared a National Park, an outcome that would have perhaps boosted “national park attendance” but without actually increasing Americans’ experiences with the outdoors.

Change park rangers’ uniforms to be more “modern” and “welcoming” resembling a hiker or jogger, so as to avoid intimidating groups fearful of law enforcement. However well-intentioned this might be, being easily recognized helps park rangers serve the public.

Allow larger groups at backcountry campsites and allow dogs, to welcome those who feel unsafe unless they’re a part of larger groups or with a dog for protection. It might indeed be reasonable to evaluate whether in any given location, campsite numbers can be increased or dogs can be permitted rather than following blanket rules, but rules shouldn’t be abandoned if there were valid reasons for instituting them in the first place.

Make outdoor recreation more affordable, for instance, by organizing subsidized transportation for poor families to get to nearby outdoor spaces, by offering free admission to state parks for first-timers, or by creating more affordable lodging at state or national parks. Some of this is obvious. (California charges $195 for its state parks’ annual pass? For a Blue State, that’s surprising, given that Illinois charges nothing, and my neighboring states a fairly moderate fee even for nonresidents.) Some of this is less so — after all, high costs for national park lodging isn’t (only) because providers wish to cater to luxury markets, but because of concerns about environmental protection, and there are ongoing disputes in some parks about how much lodging should be permitted anyway.

Make parks “cool” with music or cultural festivals. Which is all well and good until the battle royale begins over whether said music festivals are damaging the property.

and finally,

“Expand the definition of the outdoors to include smaller urban parks.” In other words, if we can’t change the underlying circumstances, we’ll just change the way we measure them, and call our actions a success.

(Yes, that’s more than five – these and other items are all sub-items of their List of Five.)

But all of this ultimately just begs the question by assuming that it’s important to “make the outdoors more inclusive” in the first place, if, indeed, the younger generation has other interests and priorities, and in particular if camping and hiking simply isn’t a part of the cultural traditions of the cultures that immigrants bring with them. REI/The Atlantic addresses this briefly in its introduction:

contact with nature leads to improved mental health, lower stress levels, and enhanced cognitive skills, for one. Plus, if more of an effort isn’t made to engage current and future generations (and this may be an especially relevant concern, as the country continues to diversify, with the U.S. Census Bureau forecasting that the U.S. will become a minority white nation by 2045), potential support for the parks “might go away” altogether, according to Michael Woo, dean of the College of Environmental Design at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

But, based on my quick check on the availability of accommodations for Yellowstone in summer 2019 (spoiler alert: pretty much all sold out), there’ll be no harm done if the national parks are a wee bit less popular. One could even make a case that we could do with fewer hikers and campers, if this leaves more of the wilderness areas truly left reserved for wildlife. And the “nature deficit disorder” referenced in the article really has more to do with having green spaces in our everyday lives than with increasing the prevalence of hiking or camping vacations.

Are we upset that immigrants and/or young adults aren’t interested in square dancing? Model-building? Hunting? Fishing? Sailing, or boating more generally? Golfing? The accordion? Isn’t it deemed a violation of multicultural sensitivity to expect that immigrants should adapt to white America’s interests? Isn’t the burden on those hobbyist-communities to share their hobby with the next generation, regardless of what skin color they are? And if they can’t make the case that that activity is attractive without appealing to cultural traditions, then tough luck, and those hobby shop or slot car racing storefronts can be used for Mariachi band instruments and quinceanera dresses instead.

It comes down to this: how do you distinguish between “hobbies” and crucial pieces of the fabric of American life (churches, community institutions) which benefit society as a whole rather than just providing fun and relaxation for those who choose to participate in them? Our current conversation has been so suffused with “tolerance” and “multiculturalism” and honoring everyone’s individual identity groups that we don’t have the space to discuss this, and to make the case that a society which engages in the outdoors is better than one that doesn’t, in the same way as is the case of a society with healthy community institutions.

What’s more, the blinders worn by those immeshed in the ethos of diversity (as well as the need to virtue-signal to their target audience) meant that this panel missed the most obvious way to reach out to prospective outdoorsmen and -women: Scouting. After all, one of the reasons (or the explanation offered by the BSA, in any case) for opening BSA-scouting up to girls, in (yes, this point is generally missed) single-sex dens (for Cub Scouts) or troops (for Scouting), was as an outreach to immigrant families, who expressed the desire for scouting to be something they did as a family, even if that took the form of a single meeting time with “break-out groups” for each age/sex den/troop. And scouting — for middle and high schoolers — includes monthly outings, usually outdoors, so that boys (and, yes, now girls) can learn camping, hiking, and general outdoor skills in a structured way, and encourages parents to accompany their children and the Scout leaders, so that they, too, can gain experience with camping even if they didn’t grow up with it. And scout camping is an affordable way for a young person or a family to begin to experience the outdoors, since the troop purchases equipment such as tents and cooking equipment, leaving for individual scouts only such items as sleeping bags, warm clothing, and mess kits, and scouts learn to be thrifty (a part of the Scout Law, after all) in camping as well. But instead of supporting Scouting (or, alternatively, alternative scouting-style organizations), those who fancy themselves socially-aware have mocked them.

And finally, even though they seek to encourage groups with the mission of encouraging specific underrepresented groups (highlighting groups supporting blacks or black women specifically and gay people in the outdoors) to hike and camp, they completely miss the role that strenghtened churches and community organizations could play. The authors propose that corporations might provide transportation to state or national parks as a charitable deed. Wouldn’t this make more sense as something that’s done as a church outing instead?

So, yes, again, this is marketing. This is virtue-signaling. But this is also another illustration of a divide that means they miss the point.

Image: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/camping/frontcountry-camping.htm