So if I were a credentialed economist, or even had any specialized education in the subject, I’d write this at Forbes. But I’m not/I don’t, so I won’t.

But I have spent the greater part of the weekend working with my teen to catch him up in his AP Econ class, and we’ve been going over the various graphs and concepts and, in particular, the connection between monetary supply and inflation that appears to have vanished in the United States.

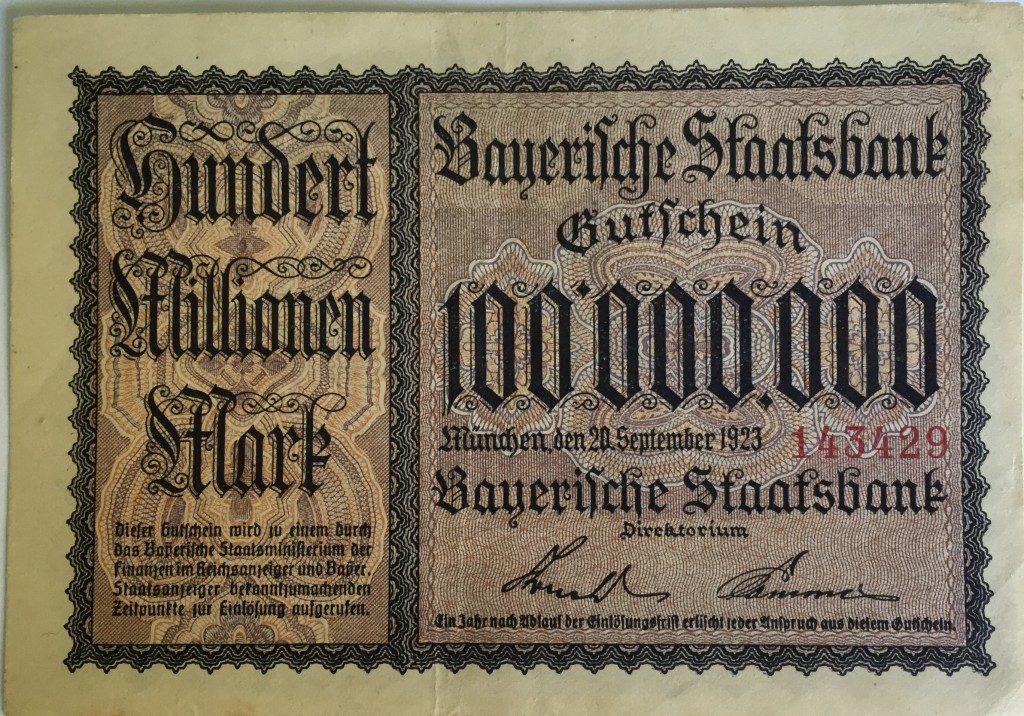

How can the U.S. print so much money, how can we engage in so much monetizing the debt (that is, the various rounds of Quantitative Easing in the past and, now, having the Fed buy T-bills rather than relying on investors to do so, particularly in use with the CARES Act money-spending) without spiking a huge inflation rate? Does this somehow prove that the U.S. is immune to hyperinflation because of the role of the dollar globally? Does Japan’s likewise substantial money-printing show that certain types of economies are exempt from the “rules” that cause trouble in Venezuela and Zimbabwe?

I find myself wondering whether we’re just measuring inflation wrong.

After all, when we measure inflation, we look at the price change in the basket of goods, and it’s assumed that the cause of changes in those price levels are broad macroeconomic effects like money supply, an overheated economy, etc.

But a price of a widget is determined by more than just the macro-economy. Consider that in the past, say, two decades, the cost of widget-making ought to have dropped considerably. For one thing, the widget factory is now likely to be in China, or possibly an even poorer country if the widget executives think China’s wages are too high, rather than in the U.S. And automation and the general increase in computing ought to have vastly reduced the widget-making overhead, too — Excel and Word, e-mail, online processes for order-taking rather than countless paper processes.

Did widgets get any cheaper? Not insofar as inflation as a whole has been increasing year after year; gradually, to be sure, but still an increase.

Why didn’t widgets get cheaper? Is it because they plowed all their excess revenue into pay hikes for workers? Not based on the stagnation of wage levels. Is it because they simply hoarded their excess profits? Basic microeconomics would say no, that in a competitive market all the widget-makers would reduce their prices so as to gain/not lose a competitive advantage. I suppose it’s possible that added costs for medical benefits — which are generally considered to be the explanation for why cash wages have stagnated — offset the cost savings for offshoring, automation, and general cost reductions due to technology, or that, in terms of the overall costs/margins for producing consumer products which feed into the CPI, the actual cost reductions due to offshoring, automation and technology in general are not as substantial as I imagine them to be. After all, in Shark Tank, entrepreneurs who are having their items manufactured in China cite costs for their products that are a fraction of what the items actually retail for.

What about productivity?

Yes, microeconomics is next semester.

But my understanding is that the standard assumption is this: prices stay stable or increase moderately due to macroeconomic factors. When there is increased productivity, that produces the historical pattern of wage increases that exceed the rate of inflation. (It seems wrong for “productivity” to include offshoring but presumably it does.) But, again, was all of the cost-savings due to automation, technology generally-speaking, and offshoring (and re-off-shoring to cheaper and cheaper locales), truly reflected in the paltry wage gains?

Or, is what really happened something like this:

Widget cost in 2000: $100.

Widget cost in 2020 (based on 2% annual inflation): $150.

Widget cost reductions in past 20 years: $100.

What widgets would cost if cost reductions were fully reflected: $50.

“Real” inflation: 5.6% per year.

Of course, this is just a hypothetical example. I have no idea how much tech/globalization have reduced the cost of products that feed into CPI.

Consider, too, quality changes. I had wanted to start this blogpost with a picture of two sweaters I had had — but I couldn’t find the second of these. You’ll just have to imagine them, instead: two “twin sets” purchased at Target a couple years ago, with pretty much the identical style. But the older one has pearlized buttons and a bit of merino wool; the newer other (though neither is particularly new; the “twin set” is fairly dated by now, anyway) is just acrylic with plastic buttons. Was there a price reduction? I don’t know. It’s hard to say, especially now that the norm at retailers such as Kohl’s is, “everything’s always on sale!” and you have to judge whether the 25% off sale is “enough” of a sale or whether you should train your eyes on the racks offering a 50% off sale. At the same time, I look at the pieces of furniture in our home — the dining room table set that’s now 20 years old, we paid considerably more for, even without adjusting for inflation, than what’s for sale at, say, Ashley Furniture — is there a drop in quality, or did prices just crater because of imports from China? And it’s my understanding that CPI calculations are supposed to take into account the sale prices and changes in quality, though whether there method truly does so is not entirely clear to me. For example, when I dug into this at Forbes, I learned that a specific item at a specific store, such as an 8 oz bag of shredded cheddar cheese, is randomly chosen and the price monitored over time, which would seem to be able to reflect sales but not whether people change their buying behavior in response to sales. At the same time, when the quality of an item changes, they’re supposed to find a different item to replace it with the quality of which has not changed during the measurement period. How precisely can they measure that? I presume the shift from jeans to yoga pants was reflected in a shift in the basket of goods, rather than taking each as a representative of “pants,” but is it universally possible to do that, to reflect moves from tailored dresses to more shapeless choices with lower-quality fabrics, for example?

In any event, again, I’m not an economist, but I’d sure like to see some inflation measure that separates out the macroeconomic factors (monetary policy, economic cycles) and the impact of wage increases, from the changes due to “productivity” (including offshoring impacts), rather than seeing the repeated assurance that the old rules about money-printing don’t apply any longer and that we are forever protected from high inflation.

Image: own photo