Are you watching the hearings? Here’s a rant. Some of this I’ve likely said before in other contexts, but here you go.

In the first place, Donald Trump has the legal right to appoint Barrett regardless of what McConnell may or may not have done 4 years ago. The fact that early voting has started in some localities, does not make Trump any less the president, and he remains president until Inauguration Day, and gets to do all the things a president is empowered to do. After all, no one is suggesting that stimulus legislation negotiation talks should end because “people are already voting” and “we’re in the middle of an election” so that our current elected officials should no longer be enacting legislation.

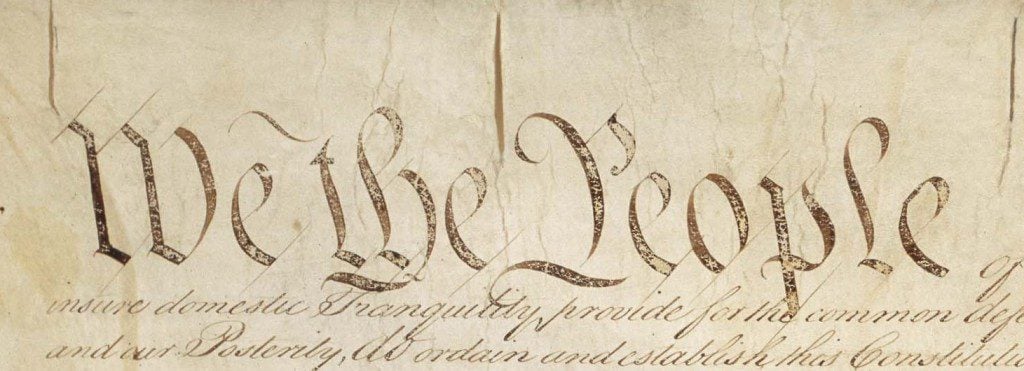

Second annoyance: twitter is chock full of people claiming that “originalism” is bad because it would mean that slavery would still exist. Whether they are being dishonest or just dumb, in rejecting amendments as a part of the constitution and, indeed, the fundamental means of changing the constitution, I don’t know.

Some examples:

An “originalist” reading of the Constitution would disqualify Judge Barrett, or any woman, from serving on the Supreme Court or from owning property or voting.

“Originalism” is a cover for deeply unpopular & un-democratic policies, not some kind of serious judicial philosophy.

— Rep. Barbara Lee (Archived) (@RepBarbaraLee) October 14, 2020

Women couldn’t vote.

Slavery was legal.

AR-15s and the internet and electric lights didn’t exist.But originalism. https://t.co/RpMRHcmKSq

— Chris Murphy

https://twitter.com/AnandWrites/status/1316037610138198018

This is, of course, nonsense.

Third, I am not sure that “originalism” vs. anti-originalism is even the right word to characterize what we’re watching play out here.

That debate exists in issues such as gun control (“the founders didn’t envision that there could be such a thing as a semiautomatic weapon, so the existence of a right to bear arms, in the Constitution as written then, can’t possibly be viewed as providing this right now”) and press freedom (“the technology of the printing press at the time the Constitution was ratified is so different than the internet, Twitter and Facebook today, so the First Amendment couldn’t possibly be viewed as guaranteed unfettered publishing rights now”), but not for most issues, it seems to me.

After all, aside from the “changing technology” issues, above, there are two types of Supreme Court decisions, generally speaking: first, in some cases, the court must assess whether a given legislation exceeds the powers the Constitution grants to Congress, or whether an action by the president/executive branch exceeds its own powers. And in other cases, the Court must determine whether a law (by the state or federal government) violates some right protected by the Constitution. (I suppose there are a third sort of issues, where the Court is called on as a final interpreter of some legislation — for example, the Bostock decision which was not a matter of determining a “right” guaranteed in the constitution but a protection of the Civil Rights Act by taking its text, and the meaning of words, as literally as possible, as I wrote about back in July.)

Of these two types, the Obergefell decision is the latter type: Kennedy determined that the “right” to marry someone of the same sex was protected by the constitution. His reasoning (which I touched on in that prior post) was a stretch, to say the least, defining “liberty” in the Fourteenth Amerdment’s prohibition of the deprivation of “life, liberty, or property,” without due process, not in the common-sense, appropriate-within-the-context meaning in which “deprivation of liberty” means imprisonment/enslavement, but as the ability to make “certain personal choices central to individual dignity and autonomy, including intimate choices that define personal identity and beliefs.”

While I am sure I had read this when it was decided back in 2015, I had forgotten about it and was floored to read this justification, this past summer, because it simply seemed so utterly preposterous. This is not “society has evolved.” This is, “I know the decision I want to make, quite apart from what the Constitution says, and the only challenge is finding some way to justify it.”

And, of course, the various court challenges on the ACA are fundamentally based on the premise that it is not within Congress’s powers to mandate that Americans purchase insurance. Quite apart from whether it is “fair” or “unfair” for Congress to do so, or whether the mandate is a “compromise” from an alternative of universal healthcare provision since that would be an expansion of Medicare that no one objects to, it is simply not among Congress’s enumerated powers (and, no, you can’t subsume this under “regulating commerce” because there is a difference between “regulate” and “mandate”). Roberts, in his 2015 decision (which, surprisingly, I didn’t really address at the time), attempted to square the circle by saying, “it’s not a mandate, it’s a tax.” Now, the decision before the Court is whether that original justification can still stand since the tax has been removed, and it’s become a “pure mandate,” but, at the same time, one without any enforcement mechanism; secondarily, and more crucially, the question is whether a finding that the mandate is unconstitutional must send the entire law toppling, that is, the question of severability. (I wrote about this at Forbes.)

But look at what’s going on at Barrett’s confirmation hearings: Democrats are spending a small fraction of their time questioning Barrett, and much more of their time lamenting the effects of the loss of health insurance if the law is deemed unconstitutional and its provisions non-severable. Here, for instance, is a clip of Sen. Kamala Harris: she spends 10 minutes lamenting the suffering Americans would experience without the ACA. She then asks a series of questions the point of which was to make the claim that Trump nominated her exclusively for the objective of getting the ACA overturned (Barrett of course said she was not aware of any such intent and had made no promises to anyone).

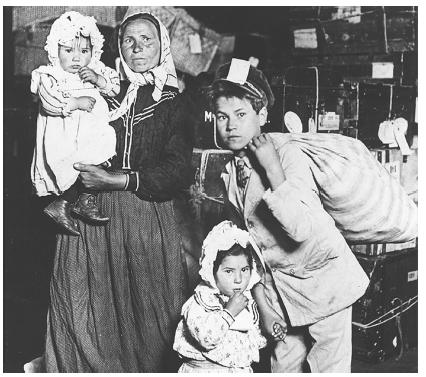

Then Harris raised the example of DACA (that is, the legislation providing renewable legal status to immigrants who arrived as children), and the impact that a ruling against its recipients would have on their lives, asking (rough transcriptions) “Do you consider the consequences of your rulings on people’s lives?”

Barrett replied, “Every case has consequences on people’s lives, so of course I do. . . . [that’s] a part of the decision-making process.”

Harris then launched into a litany of the people who would be affected by the ACA being struck down, and Barrett said that “the question would be figuring out whether [keeping the ACA] would be consistent with [their] intent” and “whether the flawed portion could be excised out.” Harris pushes here to assign a weight she would give to these impacts and Barrett replies:

“Stare decisis takes into account reliance interests. I can’t say how they would play in or weigh in this case. I can’t commit to how I would weigh specific factors.”

This line of questioning (if you can call it that, when there weren’t really much in the way of questions) repeated itself with others: “people rely on Obamacare, and its importance means it would be wrong to take into account the question of whether it is actually constitutional or not.”

All that being said, a couple weeks ago, Ryan Cooper, writing at The Week, made a proposal that was intended to be an alternative to court-packing: if the Supreme Court determines that legislation enacted by a Democratic President and Congress violates the Constitution, that President/Congress should just shrug it off and say, “whatever, thanks but no thanks,” and continue with its implementation. (I suspect he would be less happy with Republicans doing the same.)

Which gets to why I question the label “originalism”: what we’re really talking about is “constitutionalism” — that is, using the Constitution as a basis for decision-making, allowing Congress and state legislatures to legislate within their powers as defined in the Constitution and restricting them as the Constitution so restricts — in contrast a method which uses a sense of what decision would best promote fairness or justice based on one’s own principles, which would, if justices are chosen based as exemplars of justice and ethics, as individuals who always strive for the common good, be a force for good. There is, so far as I can tell, no easy label, no “ism” that fits this viewpoint, and, no, the phrase “living constitution” doesn’t do it, because the point is that proponents essentially believe that the constitution does not bind decision-making, however much they must work within the framework of “the constitution” to state their case.