They’re everywhere — proposals for a Universal Basic Income, that is.

Here’s a proposal for a “basic income” in Latvia. Here’s one for Finland, which seems to be moving forward (though The Guardian says, without further details, that it’s much more limited that various news reports claim). The Swiss will vote on this in June, though it’s not expected to pass.

My initial reaction is simply, “there’s no way we, as a country, can afford this” – but such a program would effectively be clawed back as income grows, either directly, or indirectly through tax rate increases.

And a UBI would solve two challenges with our social welfare system:

First, in the existing system, there are, to greater or lesser degrees, penalties built in for welfare recipients moving into the workforce. Not in every program — programs like food stamps are intended to meet the needs of the working poor by tapering off gradually as income grows. A basic income, with a simple clawback only after the recipient is well out of poverty, would eliminate this.

And, second, advocates of high mimimum wages expect that this alone will serve the function of getting everyone out of poverty — even though it’s blind to the circumstances of a person’s life, and, especially, family status. The wage necessary to keep a single person out of poverty is much lower than the wage necessary for a single mother with multiple kids, and it simply isn’t possible to raise the minimum wage high enough to cover the latter case.

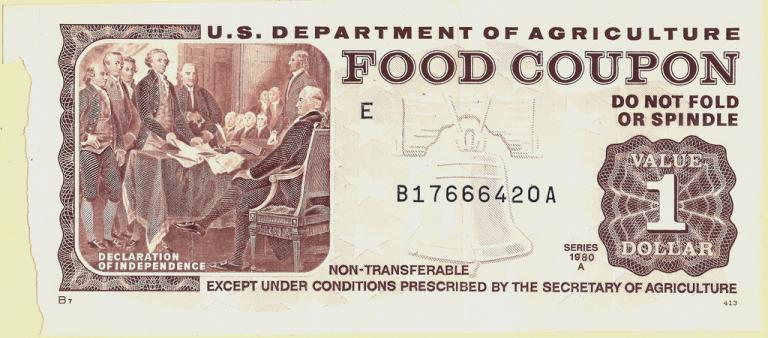

But at the same time, here’s one fundamental difference between a UBI and existing social welfare programs: the UBI is conceived of as, simply, cash handed out, per person, rather than our existing system of vouchers and allowances for food, housing, heating, phone service, mass transit, child care, healthcare, etc., with actual cash benefits going to a small number of TANF recipients. What happens when the money is lost at the casino the first week, and there’s not enough left to cover the rest of the month? Sure, everyone says, “tough luck,” but will we really be that hard-hearted? Will soup kitchens and homeless shelters still exist for the population that cannot make their UBI last all month? If so, the promise of “one and done” welfare won’t come to pass. And even if we’re willing to shrug off the adults, we won’t be able to ignore the needs of kids.

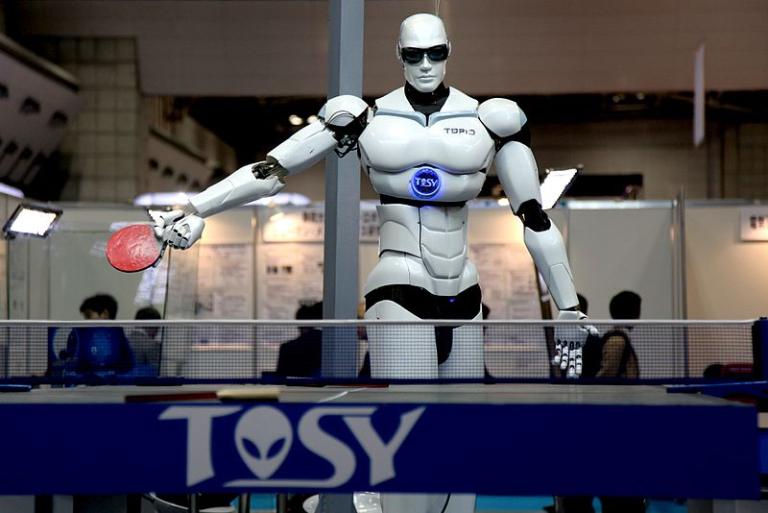

Besides which, there seem to be two types of Basic Income supporters. The futurists imagine that robots will eventually do all our work for us, and work will more or less disappear, so that the bulk of the population will live off their Basic Income. These supporters expect that the Basic Income will be sufficient to provide a middle-class standard of living, and envision that some recipients will work, and others will be great artists, or authors, or do other socially productive things. But this is really more fantasy than anything, isn’t it?

The alternate approach comes out of welfare reform plans. Provide a basic sum of money, enough to provide the necessities of life. No, a single recipient won’t be able to afford an apartment, complete with cable and internet and an Xbox One. That person’d have to get roommates, or find an SRO (which, in my view, ought to be easier to do than it is — though the funds should be enough to enable something better than Hong Kong-style cage homes). And restaurant meals would be out of the question — a crock pot and plenty of bean and rice recipes would have to be good enough. (Should the basic income be higher in high-cost areas? Probably not – they’ll just have to move.)

The assumption is that this would be paired with a very low minimum wage (or even none at all). Educated, middle-class workers wouldn’t even question the need to continue to work, and the unskilled and uneducated would also work, to supplement their basic income, even if their productivity, and their wages, are low, just because the living standard would be so low otherwise. Would it work? Would it be possible to strike that balance — a basic income low enough to motivate its recipients to work to supplement it, but not so low as to produce human suffering for those who can’t find jobs at any wage, or are unable to work? This is the core difficulty, and I think not possible to resolve and the key reason that UBI isn’t implementable. As soon as the UBI is high enough to meet the necessities as we would define them, so that a jobless person doesn’t genuinely suffer, there will be far more people than we, as a society, would like, content to live off it, jobless, like the “welfare queens” of old, or as is the case in European countries with generous supports for the long-term unemployed/nonworking population. Add to that the fact that a fixed UBI can’t be one-size-fits-all because people aren’t one-size-fits-all, in ways as simple as regional cost of housing or having a paid-for house or a stable roommate pairing, to the complexities of kids of different ages and spending needs (is your three year old still in diapers, or not?).

(Of course, there’s a third variant, another sort of fantasy that imagines that a basic income would be paired with a high minimum wage. The basic income would be, in this scenario, a fallback so that people who are no longer able to find work, are taken care of.)

The bottom line is that a UBI is great in theory, but not in practice, which means that it’s not so great in theory, either.