So having given a more-or-less straight summary of $2 a Day in my prior post, here are my observations:

Edin & Shaeffer start off with “$2/day poverty has doubled since welfare reform” but other than that, the book is pretty void of statistics. What were the baseline numbers? When they say that virtually no one gets TANF these days, and the states use their block grants for other purposes, it really requires some hard data. They also breezily say, offhand, that in the pre-welfare reform days, welfare clients faced benefits loss on a $1 to $1 ratio if they started earning a paycheck, but nonetheless, they’re pretty confident that the prior system of benefits indefinitely without any work requirements had no effect on recipients’ willingness to work.

They also didn’t discuss drug use/abuse at all: none of the individuals they profiled, nor any of the other people in their lives, used drugs except for cigarettes. Presumably this was either a choice, to make the individuals more sympathetic, or a result of the drug users being even more in the shadows and less likely to be willing to be interview subjects. But it does matter. It may even have been that, as an Amazon reviewer pointed out, the toothless mother was so not because of faulty dental care as a child but because of drug use that she declined to reveal to the interviewer.

Another thing that’s not mentioned is street-corner begging. Certainly not effective in the Delta, but what portion of the poorest make their way to downtowns, intersections, etc., asking for cash, and how much to they take in?

With respect to the single mothers (though not all of the interviewees are single mothers), child support is virtually nonexistent. Perhaps the fathers are just as unemployed, but they ought to at least be more employable, without children to care for, and there’s a big gap if the state makes no effort to pursue child support in these cases.

About the Delta? Well, this is where Kevin D. Williamson’s case for giving them a U-Haul is pretty strong. Edin and Shaeffer describe that region as almost wholly lacking in jobs, and similarly lacking any reason for any employer to set up shop there, with a level of poverty that’s so entrenched that it’s practically another world. And its isolation makes life even more difficult for the poor there, since there isn’t the same charitiable infrastructure; there are no food banks or school supply distributions, nor any mass transit for those without cars. But why should the government just permanently support these people solely so they can hold on to places because that’s where their mothers and grandmothers lived? (After all, large portions of their neighbors have left already.) Yes, there is no longer any specific region with a “pull” in the way that Northern cities pulled ex-sharecroppers in the 1960s, but there is still no point in trying to support these people “in place.”

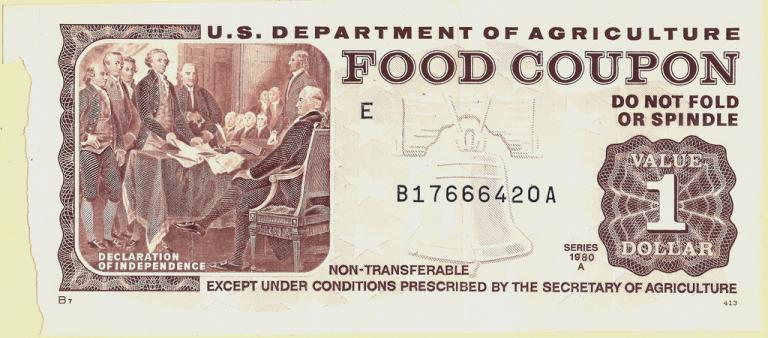

And Alva Mae, the woman with thirteen children who go hungry because she sells the food stamps at 50 cents on the dollar to pay bills? I just can’t comprehend that. The authors excuse her because her second husband/partner was abusive, but this says that, in 8 visits to the hospital in as many years, as well as trips to get food stamps (and presumably WIC), no one did anything, said anything, offered any kind of contraception, let alone help leaving an abusive situation — or she rejected the offer. The answer for the Alva Maes of the Delta, or elsewhere, is not more cash. The answer is intervention far before they reach this point — and, no, I’m not saying that they should have been sterilized, or required to accept a contraceptive implant as a condition of receiving government benefits, but that they need services from a social worker, a restraining order against the abusive boyfriend, and, I don’t know, perhaps the whole family, mom included, needs to be in a “foster home” of sorts, or a shelter-with-services, even if they’re not technically homeless, and they need to get the h*** out of their small town.

(Incidentally, that’s the trouble with dreams of a “minimum income” as a replacement for welfare: cash alone isn’t enough to remedy the poor decision-making, drug abuse, domestic violence, etc.)

One thing that was a surprise: the lack of phone service. What about the whole scandal of the readily-available “Obamaphone”? From all reports, this required no long wait in a welfare office, and, even though the program has been tightened, it still exists — and you’d think that the homeless shelters would have been able to provide the relevant information to their guests without phones.

Other elements of the book that were troubling: families having trouble finding a homeless shelter that would take them in, and three-month limits on stays in those shelters. The lack of dental care for adults; charities are happy to help children but not their parents. And, yes, you’d want people to take care of their teeth in the first place, but some level of access is important if that’s not happened.

About housing cost, Edin & Shaeffer acknowledge that a part of the reason for its growth is that there’s an increase in living standards: from indoor plumbing to hot water to air conditioning, these items all have costs. They further claim that a reason why housing appears less affordable is that wages have stagnated, but they use a mistaken metric, assessing whether an individual earning minimum wage could afford a two-bedroom apartment “at the fair market rent” — which they don’t source but is likely taken from the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s Out of Reach report, which takes as its metric the 40th percentile rent for a “typical non-substandard” apartment, including utilities, and which doesn’t reflect the fact that, in reality, it’s reasonable to expect that the very poor will live in the cheapest available, not the 40th percentile, apartments. But be that as it may, there’s a whole issue around the fact that policymakers have simultaneously cheered (and encouraged) growth in home values, as a marker of economic prosperity and asset growth for homeowners, and simultaneously been shocked at housing cost. And regardless of all of this, no one can afford a place to live without an income of some kind.

Edin & Shaeffer also write near-simultaneously of the need to raise the minimum wage, and the fact that, at the bottom, the very poor have a exceedingly difficult time finding a job. They propose to remedy the latter problem through government jobs, but the list they give is not exactly filled with the sort of jobs that a person with no skills can do — infrastructure/construction work (how many flaggers do you need?), day care teachers, elder care, staffing libraries, pools, homeless shelters.

It strikes me that, as a result, what we need, for the poorest and least skilled, and those who will not be able to get their lives together enough to develop those skills, is a combination of a subminimum wage together with a souped-up EITC, paid out directly in the paycheck, so that employers who are able to offer the sorts of jobs that are suitable for such individuals, would be willing to do so. (The authors discuss a program called the TANF Emergency Fund which provided temporarily employers with incentives to hire TANF recipients or other long-term unemployed people, which would have had a similar impact but not as wide-ranging.) Yes, this would be similar to the subminimum wage paid to disabled individuals, except that it would be based on the simple issue of for how long the individual had been out of the workforce, rather than some kind of test of work skills, which wouldn’t really be feasible if what your measuring are intangibles like ability to show up on time, and interact appropriately with colleagues and customers, and potentially basic educational pieces like literacy and numeracy, and an overall reliability question that prevents them from getting the job in the first place. I toyed around with this idea a while back in the context of minimum wage hike debates, but even absent a minimum wage hike, perhaps a subminimum would get employers to give these long-term unemployed, unskilled people some consideration.

At the same time, I like the author’s endorsement of job supports, and, let’s face it, if TANF is MIA even for those families for whom it’s designed in the first place, well, this should be remedied.

What would you do?

Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AHelping_the_homeless.jpg; By Ed Yourdon from New York City, USA (Helping the homeless Uploaded by Gary Dee) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

![https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AHelping_the_homeless.jpg; By Ed Yourdon from New York City, USA (Helping the homeless Uploaded by Gary Dee) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/533/2016/04/Helping_the_homeless.jpg)