This book is not a polemic. It largely busies itself with simply explaining the lives of those in deep, deep poverty, both in general and by means of a small number of case studies, with some context to begin with and prescriptions at the end. The book doesn’t assign villians, or launch into partisan rants, and it doesn’t portray the people it follows as either paragons of virtue or deserving of their fate. And the name of the first co-author seemed familiar, and, turns out, she co-authored another book I read a while back, Promises I Can Keep, Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage, which I summarized in an early blog post.

Is the book perfect? No, of course not. Through the negative reviews on Amazon, among other comments, point out that the authors take the stories their subjects relate as entirely truthful, when it’s just as likely that the woman with no teeth came to that fate not by lacking dental care but by drug abuse (and drugs are wholly absent from the case studies), and the women fired for $10 missing in the cash register might will have been stealing, rather than being terminated out of the blue. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s start with description before getting into opinions.

The fundamental data point of the book is this: based on analysis of the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), an estimated 1.5 million households with 3 million children had cash income of no more than $2 per person, per day, in any given month. Maybe this figure is inaccurate, and overstated due to individuals working under the table and not reporting the income to the survey-taker, but, regardless, what is noteworthy, and cause for concern, is that this figure “more than doubled” (though this isn’t quantified) since welfare reform was implemented in 1996.

To some degree, this shouldn’t be a surprise, what with TANF’s limits on lifetime benefits. And Edin & Schaeffer don’t simply rage against the reform: they acknowledge that it directed significant benefits to the working poor, especially those with children, via the Earned Income Tax Credit, and that has improved the wellbeing of a great many families, and, indeed, there was a major shift off the welfare rolls and a significant reduction in child poverty on an overall basis (p. 30). What’s more, welfare reform has produced a cultural shift among the poor:

[W]elfare reform coincided with a fundamental shift in the way low-income single mothers thought about parenting. In the years prior to welfare reform, in-depth conversations with hundreds of single mothers on welfare illuminated their belief that taking a full-time job would greatly detract from their ability to be a good parent, especially if they had young children. Then came the roaring 1990s, when an unprecedented number of these single mothers found themselves going to work, “pushed” by the changes in the welfare rules and “pulled” by the EITC expansions, minimum-wage increase, and unprecendented strength of the economy.

Years after welfare reform, when researches engaged in a further series of in-depth conversations with former welfare recipients, the typical single mom talked about work in a very different way from those interviewed just a few years before. Now she was telling researchers that to be a good parent, she had to model the value of education by getting a job (p. 32).

This is clearly striking. Yet, the authors report, for those who can’t get a job, times are tougher than ever. Even for TANF, the conventional wisdom among the poor has become “don’t bother applying; the lines are too long and you’ll just get rejected in the end” — and they further quote poor women who are convinced it doesn’t even exist any longer at all.

And the long-term unemployed have additional strikes against them: convincing an employer to hire a homeless shelter resident, or someone dependent on mass transit, or someone without a proper work wardrobe or a means of showering daily and keeping clothes clean, or a toothless applicant, is all the more difficult, especially in a weak market when that employer has other choices.

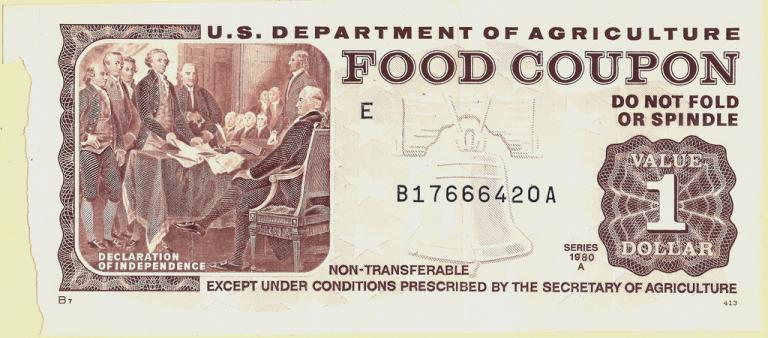

How, then, do they survive? They write of various efforts to acquire cash: one woman they profile donates plasma as many times as the donation center will allow. They collect recyclables (though they’re limited by their ability to store and transport them). Another operated a small store selling snacks in her tiny Delta town, using food stamps to buy inventory at the grocery store in a town further away, then selling it in her living room, marked up. They sell food stamps; the authors say that the USDA’s recent audit determined that food stamp fraud occurs at a level of 1.3% of overall benefits, but among the cashless poor, this seems more routine. (In one case the authors cite, a mother-of-13 in the Deep South, she sells so much of the food stamp benefit that the kids are seriously undernourished.) They sell access to the kids’ Social Security numbers for others to use to claim the EITC, splitting the proceeds. And the women sell their bodies, not necessarily in the form of prostitution per se, though this happens as well, but in the form of a “friend” with whom there’s an understanding that they have sex and he covers some of her expenses. In other cases, households fall below $2 per day because a member of the household collects Social Security disability benefits, but that case must stretch for larger numbers of dependents; in the family they profiled, a man supported his wife and several grown children and their children, 22 in all, in a three-bedroom house, on his Social Security disability benefits.

These individuals also learn the ins and outs of every charitable benefit: the soup kitchens or food giveaways, the backpacks when school starts, the winter coats, the free clinics, and so on.

And, as far as housing is concerned, they double-up, they triple-up, they bounce from one shelter to another, they stay with any relatives who’ll take them.

The people she profiles, though lacking jobs now, have worked in the past — several who were cashiers, another cleaning foreclosed houses, another as part of a hotel housekeeping staff, and other such unskilled work. One (the disabled grandfather) even owned several pizza restaurants, but lost everything. And they continue to look for work, pounding the pavement without success. Why did they lose their jobs? In one case, a transportation failure. In another, an accusation of theft from the register. The housecleaner quit because the fumes and chemicals from these houses were making her sick. In others, it’s simply blamed on the economy — but there’s also an acknowledgement (though excused by poverty) that these people are not entirely mentally stable, and prone to making bad decisions.

What do the authors prescribe as solutions?

- Job creation: both in government subsidies to private employers and large-scale expansion of government jobs.

- Supports for workers, such as emergency transportation or child care and advocacy in helping workers keep their jobs.

- Boosts in the minimum wage.

- Pursuit of wage-theft violators.

- Require employers to schedule work with enough advance notice that workers can plan, and can succeed in holding onto their jobs.

- Revive cash assistance for those without work.

So that’s my summary. Commentary coming next.

Image: By Raysonho @ Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

![By Raysonho @ Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/533/2015/02/library.jpg)