The title is, of course, a play on Jesus’s statement, “the poor you will always have with you,” made when a woman anoints him with costly oil and one of the disciples flips out and says, “that money could have been spent on the poor.” Jesus then follows that up with, “you will not always have me” (Matthew 26:11), and praises the woman’s deed as anticipating his coming death. I’m reminded of that not just because of the passage itself, but because of some reading I did in grad school; medieval theologians analyzed this passage and concluded that it was not just a throwaway line but had great meaning. Why were the poor to always be with us? So that everyone else had recipients for their charity, for one thing, as I recall.

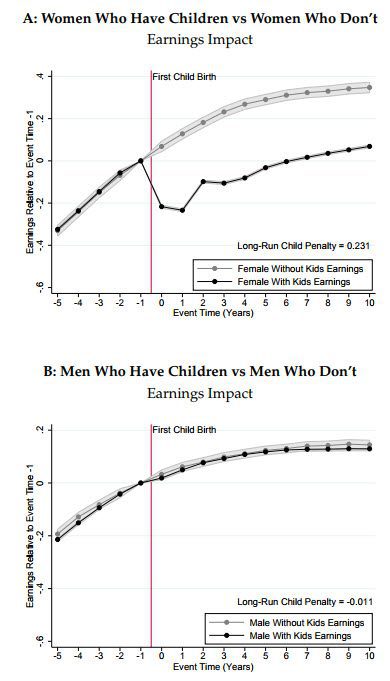

That particular passage, and the discussion it inspired, came to mind with respect to an article that came across my twitter feed the other day, “Children and Gender Inequality: Evidence from Denmark.” The first time it was shared, I didn’t really notice it much: the basic argument is that it is not being female that is the cause of a pay gap, but specifically being a mother, as 80% of the pay differences between men and women are explained by “child penalties” (though the authors also comment in a footnote that they use the label “penalty” consistent with current usage in the field and not to express a belief that these are objectively penalties). The authors note that sex-based pay inequality stands at 15 – 20% in both the US and Denmark “and appears to have plateaued at that level.” The article is very dense and I’ll admit that I only skimmed the methodology section, but here are the key graphs (page 42).

Which are pretty dramatic differences, but something that makes sense intuitively. After all, mothers are disadvantaged by the lack of paid leave, the high cost of child care, and so on.

But, as I said, this is Denmark, and that’s the surprise in the report.

In total, parents in Denmark get 52 weeks of paid parental leave. The general rule is that the mother has the right to four weeks of leave directly before the planned birth and then to a further 14 weeks of leave after birth.

The baby’s father is entitled to take two weeks of leave during the first fourteen weeks after the birth of the child. Then 32 weeks follow where the mother and father can freely share leave between them. They can choose to be on parental leave at the same time or in periods one after the other

according to Oresunddirekt.com.

And

Denmark is a pretty good place to raise children.

Working hours are short, and it’s perfectly OK to leave work at 3 or 4 o’clock to pick up your kids. There’s a good system for early childhood health. A nurse visits your home when your child is a baby. Later, there are regular checkups with a doctor.If your child has the sniffles, you can take off work and stay home with her. The first two days are paid time off.

And, of course, there’s the day care system. It’s not free, but it’s reasonably priced, and it’s nice to be able to drop off your kid in a safe place with trained people while you go to work.

In some countries, there’s a lot of controversy about whether very young children should be in day care or at home with their parents. Not in Denmark. 97% of kids go to day care, even the children of the Royal Family. Even the future king, currently known as ten-year-old Prince Christian, went to day care.

Everyone goes to day care partly because the Danish tax structure means both parents have to go to work.

But Danish day care is also social engineering. It’s about creating that equality and community spirit that everyone prizes in Denmark. Day care is the first step in making your child more Danish than wherever you come from.

According to How to Live in Denmark.

Now, it’s true that there are suggestions that the issue is that even in Denmark, the level of social engineering is insufficient. An article at Bloomberg earlier this year by Leonid Bershidsky suggested that the remedy is mandatory parental leave of equal length for mothers and fathers, with no transferability, so that fathers are obliged to spend the same amount of time caring for their infant children as mothers.

A country mandating equal, completely non-transferable family leave for both men and women would begin to degrade the stereotype propping up the pay gap. If men and women must both take time off to take care of a child, and if they are actively encouraged to put equal effort into child-rearing — something that can only be good for children — employers will cease to regard men as the more committed workers.

Now, the article in question refers throughout to “mandatory” leave, and I’m not entirely certain whether the author simply refers to the system of government benefits-in-lieu-of-pay and permitted time off as “mandatory” or whether he envisions employees being absolutely required to leave the workplace for the specified length of time. But whether or not men take time off while their children are infants, says nothing about the expectations and preferences of mothers and fathers over their careers, in terms of hours worked, dedication to career advancement vs. parenting and other non-work activities, and so on.

Which means that, if the extensive social engineering of a Scandinavian country like Denmark hasn’t “fixed” the gap, it raises the question of whether it’s “fixable” or whether trying to “fix” it is even a goal we should attempt to achieve.

Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AUS_Navy_050114-N-3659B-050_he_Morale_Welfare_and_Recreation_Child_Development_Center_on_board_Naval_Support_Activity_Mid-South_in_Millington%2C_Tenn.%2C_provides_daycare_services.jpg; By U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 3rd Class Joseph M. Buliavac [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons