At the heart of Lent lies desire—the desire for unity with God, the desire to serve him even to the point of virtual self-abnegation. Purgation is itself a side-effect of this eros, an erosus, a corroding of ourselves so that we may fall, broken and holy, at the foot of the Cross.

Though I imagine the Greek and the Latin are not actually etymologically related (and I am a medievalist, so faux- or folk-etymology really is my field), there’s a truth embedded in this connection. Lent means letting all our sins corrode and fall away, saturated with the dew of the Lord.

Our medieval brethren were occasionally fond of depicting Jesus as a giant wound, a wound often conflated with the vagina, or sheathe, that is with the vagina as we understand it (exempla may be found here, here, and here). As the late Orthodox priest, Fr. Thomas Hopko puts is in his reflection for the fifth day of the Lenten fast:

The theme of man’s exile from God, his estrangement from the true spiritual reality to which he belongs, is constantly repeated in the lenten [sic] services. We are not home. We are not where we belong. We are alienated and estranged. We are in exile…The things of the world creep up on us to destroy us. We hardly notice it happening. Lust and pride and covetousness begin, little by little, to take over our lives. Their enslaving power always begins with little things…The small temptations, the petty demons, the little sins, so seemingly innocent, insignificant and harmless, must be dashed upon the Rock of Christ. Otherwise they grow big and become strong and destroy the heedless and negligent with their lethal power.

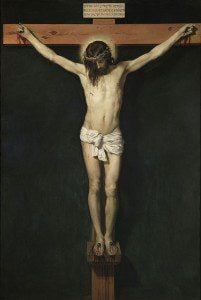

Our sights must remain set on the only goal, the only sensible thing worth striving for—Christ crucified, the rock upon which our little sins may be dashed. Some medieval illuminations depict Jesus birthing us, His Church, from His side; but, with certain Freudians, we might say that we also want to return to His very side, whence we come.

It is this desire that drives Lent, that carries us from the joyous introspection of Ash Wednesday to the foot of the Penitent Thief on Good Friday, for we know that all we can strive to be is penitent, unworthy, yet miraculously recognized by Christ’s tearfully triumphant gaze, drenched in the blood and viscera of the God-Man.

This itself, since we’re in a medieval mood, might remind us of Fulgentius’ allegorical interpretation of “the Fable of the Goddess Psyche and Cupid” from his Mythologies (an immensely popular work in the Middles Ages). Cupid is the Roman form of Eros, the son of Venus, who, sent to spite the beautiful Psyche, falls in love with her. She accidentally burns him with the oil of a lamp and, after doing a series of labors, is allowed to wed him; she thus becomes a goddess:

Venus envies her as lust; to her she sends greed (cupiditatem) to do away with her; but because greed is for good and evil alike, greed is taken with the spirit and links itself to her, as it were, in marriage. It persuades her not to look upon its countenance, that is, not to learn the pleasure of greed (thus Adam, although possessing sight, does not see himself as naked until he eats of the tree of covetousness), nor does she agree with her sisters—that is, flesh and free will—that she should satisfy her curiosity concerning its appearance, until frightened by their insistence she produces a lamp from beneath the bed, that is reveals the flame of desire concealed in her breast and loves and adores it [because] now it is seen to be so delightful.

Greed, since it is for good and ill, is desire. Fulgentius will go on to give a negative reading, but we can imagine the soul, Psyche, finding itself illuminating desire, within us—the desire for Christ, a desire that eventually leads to theosis, or our soul’s deification. Eros, sent by love (Venus, or, in our Christian reading, God), leads our souls to Paradise.

And this, the call to put ourselves aside and to let love guide us to Calvary, constitutes the erotics of Lent.