Source: Flickr user jon rubin

License

Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (1981) begins where it ends. On its surface, there’s nothing all that remarkable about this fact. You might even call it “effective leveraging of form” or simply “good writing.” In more heavily declined languages like German, the first position in a sentence is emphatic. Wir gehen jetzt. Jetzt gehen wir. The latter emphasizes the “now.” It might better be translated “get your ass in gear” or “I’m offended. We’re out.” In Latin, both the alpha and the omega positions draw the reader’s eye.

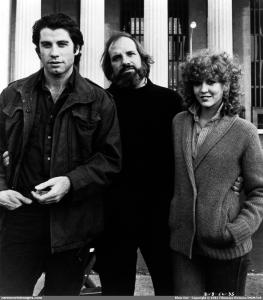

What might make Blow Out’s chiasmatic structure even less noteworthy (though who can say with how cinema is going today—ask Martin Scorsese): its beginning sets up its end. The film opens with footage of a killer breathily lurking outside a sorority house as a heartbeat and synth score underwrite the tension. Bits of Slasher-esque comedy pepper the scene. A nerdy girl complains of neighbors discoing in their undies, and a girl masturbates about as brazenly as is possible. The sloppy camerawork is not typical of De Palma. Sensible enough since we crescendo to a co-ed in the shower who lets out the wimpiest scream ever recorded. This is not a De Palma at all, but a low-budget Slasher under review in a theater. Jack Terry (John Travolta) sits and smirks as his producer Sam (Peter Boyden) berates him for the crappy yelp. Looks like Co-Ed Frenzy needs some new sound effects. Sam, unconcerned that he brought on the girl, notes that he “hired her for her tits, not her scream.”

Jack heads out into the dark Philadelphia night to record new sounds only to record a horrific accident. He saves a girl, Sally Bedina (Nancy Allen), from drowning alongside her gentleman caller. But was it an accident? Unlike in Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), which clearly inspired this movie, we will soon know that this was murder and only Jack can grope his way to truth. A former army communications man and police-sting wire operator, the now-sound guy has to save the girl, defeat the maleficent forces behind the assassination, and win the day.

But this is a De Palma film, and his Hitchcockian protagonists never have an easy road to peace. Here, the movie’s structure becomes more remarkable. Jack is, like Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window (1954), a troubled and powerless voyeur. He begins the movie in a theater, shares his experience of accidentally causing a an anti-corruption mole’s death, and ends up tailing his new love as she flirts with doom. Blow Out works by repetition. In nearly every scene involving Jack, he’s walking, using recording equipment, or watching something or someone uneasily. De Palma underlines this repetition with split screens and split diopters.

The credits, for instance, play over a split shot of Jack preparing sound effects as a TV news anchor discusses the upcoming Liberty Day Parade. Sounds pile up as the voice drones on. We cut to a park at night where Jack points his microphone taking in a variety of new sounds, dislocating the old loops, even as he stays within the same fundamental logic: sound puncturing, moving around, still air. These repetitions are not exact (as no repetition can truly be), but by splitting the screen, De Palma plants the crumbs of one moment in the next. One of the reporters from the credits will be back, as will the politician from the footage. The sounds he initially plays (broken glass, for example) will return in the accident, even as he accrues new ones (like an owl hooting). The movie is linked by these constant displacements. Always new, always the same—Jack Terry, despite the adventure he has in store, will remain the same powerless viewer.

Sure, this builds tension. But its purpose is dual here. By repeating elements so often and linking them through the use of splits, De Palma mirrors Jack’s own paranoia, the nightmare that weighs on his ragged brain, beginning before the film even begins, carrying through his attempt at heroism all the way down to the conclusion.

Forgive the medievalist in me, but I couldn’t help but note that this is an old device, a way to sever order and suture disorder at the same time. Perhaps better known for Gawain and the Green Knight, the same poet has handed down another gem, Pearl, a poem in which a father laments the untimely passing of his young daughter. He too is powerless and sets off on an adventure (in this case, a dream) to see if he can save his daughter or at least understand where and what she is now. Pearl is an alliterative poem and therefore bound by constant consonantal repetition. The poet does now cease there, however. He ties sets of stanzas into sections by beginning and ending each one with a specific word somewhere in the lines. Better yet, he ends and begins the poem with variations of a phrase: “Perle, plesaunte” (1) and “precious perles” (1212). Both lines end in the same word, “pay[e]. His grief, whatever resolution it comes to, is contained in these repetitions. And yet, his language is the same. He is stuck like his pearl in the mud. In the poet’s rigorous knitting and unknitting, we feel the abysmal sadness of powerlessness in the face of loss. And yet, we see that there is hope, even if such hope is delimited by language itself, by the turns of phrases, the diction, with which we began.

With De Palma, there is rarely such hope. Nonetheless, the device works the same. Order is disordered and chaos is brought to a semblance of peace (catatonia being a kind of quietude). We end where we began: powerless in the face of forces we can but dimly know and poorly grasp.