Source: Flickr user Mahesh Sridharan

License

Empire Records (1995) is a cult hit. Having been born in 1993, I missed out on the phenomenon. In preparation for seeing the stage-musical adaptation of the Allan Moyle film, I decided to check it out. It’s fun in its way. Teen comedies are, well, for teens. And I can imagine enjoying this movie in a right-place-right-time sort of way. I’d wager the musical would be better (the movie never leans into its song choices). But I had to miss the show at the last second. C’est la vie.

What I couldn’t shake, however, is just how Gen X the movie is. Hold your horses. I don’t mean that as a compliment. Like a black light in a hotel room, it does an excellent job of highlighting just what the implicated want hidden. Empire Records, like Eliot’s shadow, exists between the motion and the act; it gives us Gen X denuded, somewhere between the self-conception and the reality (it is a film after all, not the real thing).

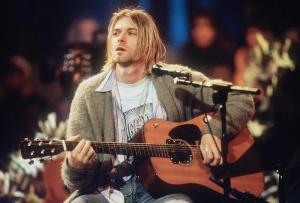

Gen X’s self-conception now has to do with forgetfulness. Sandwiched between the ever-to-be-remembered Boomers and the culturally dominant Millennials, they take to the realm of generational memory-holing like a hairy elderly gentleman to a sauna. Smugness comes along, typically. This inability to care is supposed to be their trademark: no one remembers me. And why should they (all the while enjoying reminding people they are forgotten)? Vide Kurt Cobain, Gen X’s mascot, the king of cool disaffection, the harbinger of 90s slacker culture.

Empire Records puts all this on display. The employees of the store are slackers; they love playing little practical jokes and ragging on one another. They stand up for their little record store over and against “the man” (does anyone remember “selling out”? Adbusters?). But that’s not all. There’s what I would term a purity, a naivete at the heart of the film.

It’s not just that the characters get along with their older manager (who is cool and not square like their boss’s boss). It’s not just the obsession with coolness for its own sake. No. These characters are earnest. At bottom, each of them has a heartfelt problem or desire that the movie seeks to resolve—with no irony or complexity or any other word ending in “y” you can call to mind. Each is a very special episode all their own; each has a kind of 50s purity dressed up in grungy plaid.

One has a drug problem, which, though barely touched on, marks her: otherwise, she is perfect, academically, socially, and in terms of appearance. Her best friend says as much. The best friend’s issue is that she’s jealous of her own friend’s perfection and so sleeps around. One of the boys, with whom we begin the movie, reeks of disaffection. At first, I thought the character was supposed to be well meaning and simple, rather than a kind of bohemian sage. Of course, his ironic distance disappears when his confreres need him. Everyone, excepting perhaps the owner of the store, has puppy-dog eyes and a heart of gold.

Yes, yes—this is a teen movie. I was not expecting complex characters or multifaceted motivations. But that’s not the point. What struck me, really cut deep into my sense of generational consciousness, was how much this reminds me of Gen X’s self-presentation now: cool, wise, detached, Cobain-like, though ultimately and unconsciously goofy and naïve—even cringe to the younger age cohorts. They lack Gen Z’s utter and complete disaffection, its total comfort in a world of depravity, in which no one can expect anything. Get the bag; stay alive.

Not so for Gen X. There’s something softer, more genial buried underneath all the flannel cosplay and disaffection. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course. I guess it’s been with them from the very beginning.