Christianity has always been radical. That sound trite, but it is indeed true. Love your enemy? Pray for your persecutors? Give away everything and follow a 1st-century Jewish God-Man? Nothing in that is either easy or normal. Christianity not only draws the outsider in but also pushes the insider out. Just ask St. Peter, bumpkin-fisherman, and Abba Moses the Ethiopian, former bandit turned desert hermit, how they feel about the “normal.”

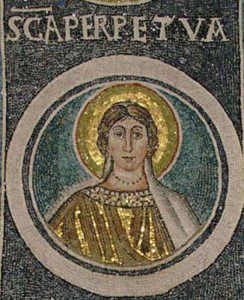

And so, in this “post-Christian” age, we actually have an enhanced opportunity to do the Lord’s work. We are invited to return to a cognizance of our own oddity. Though different, there exist parallels between our own time and that of pre-Constantinian Rome. Among many early saints, there was little excuse for violence. Because such force reigned in the community-at-large, non-violence made sense. It was actually easier to take the Sermon on the Mount literally when one was so readily confronted by the norms of a pagan culture. Here, I have in mind St. Perpetua, whose partially-autobiographical martyr-story declares just this.

In a vision, she finds herself in an arena, turns into a man, and mercilessly beats up her opponent. For her, this dream signifies, in part, that she is not to use force to fight man, but to use good works to fight the Devil:

When I walked up to the trainer and took the branch…He kissed me and said to me: “Peace be with you, my daughter!” I began to walk in triumph towards the Gate of Life. Then I awoke. I realized that it was not with wild animals that I would fight but with the Devil, but I knew that I would win the victory. So much for what I did up until the eve of the contest. About what happened at the contest itself, let him write of it who will.

When the time comes for her actual martyrdom, Perpetua is so absorbed in mystical ecstasy that she doesn’t even notice she’s been assaulted by a wild animal:

There Perpetua was held up by a man named Rusticus who was at the time a catechumen and kept close to her. She awoke from a kind of sleep (so absorbed had she been in ecstasy in the Spirit) and she began to look about her. Then to the amazement of all she said: “When are we going to be thrown to that heifer or whatever it is?”

When told that this had already happened, she refused to believe it until she noticed the marks of her rough experience on her person and her dress. Then she called for her brother and spoke to him together with the catechumens and said: “You must all stand fast in the faith and love one another, and do not be weakened by what we have gone through.”

This is weird, and it’s supposed to be. Perpetua, in the course of her narrative, mystically turns into a man, absorbs the blows of gladiatorial beasts, and experiences religious ecstasy, all without actually fighting back.

With the union of the Church and Roman state, things get more complicated; one can see Augustine, at the beginnings of this period, wrestling with new political questions. In fact, he reverses his position on whether state force can be used to coerce the Donatists multiple times.

But my point here is not politics, it’s merely that the actions and circumstances validated by the Church have experienced pressure from the outside. Early martyrs saw resistance to (otherwise legitimate) authority as sanctifying, while newly-constituted Christian authorities had to explain how Christians could use such forceful means at all. This work continued straight through the medieval period when debates over whether or not the Church could even hold property caused treatise after treatise to be written (a few examples, representing multiple positions, here, here, and here).

Now, however, we’ve lost the state (and to some extent, the culture) all over again. In my mind, this Death of God, is an invitation to dialogue with just these sorts of stories, a suggestion to re-cognize just how non-normative the faith is.

Slavoj Žižek has recognized this potency time and time again:

What I like is to see the emancipatory potential in institutionalized Christianity. Of course, I don’t mean state religion, but I mean the moment of St. Paul. I find a couple of things in it. The idea of the Gospel, or good news, was a totally different logic of emancipation, of justice, of freedom… [T]he message that the Gospel sends is precisely the radical abandonment of this idea of some kind of natural balance; the idea of Gospels and the part of sins is that freedom is zero. We begin from the zero point, which is at least originally the point of radical equality.

This is the man who has also claimed that monogamy, and marriage in particular, is among our most radical acts.

Here, in a not un-Žižek move, I’d like to turn to our popular culture, specifically to the up-and-coming rapper, Young Thug. His whole identity is critique; his name is so direct as to be a parody of rap’s machismo, an attack on this culture, a signifier that turns its expected signification back onto the reader. He wears mostly women’s clothing (though not in an overtly feminine way. Examples here and here); one of his most popular songs has the name “Best Friend,” and he even calls his male friends by pet names like “boo” and “bae.”

Some see a critique of homophobic rap culture here, but I see something quite different. Young Thug represents rap culture’s confusion, and, in a sense, its capitulation; under the weight of its own popularity, rap’s masculine posturing has been forced to introduce elements from the prevailing culture. Whether consciously or not, Young Thug is bringing these contradictions to the fore; he’s living the question of how one raps in the age of queer theory. Insofar as rap represents an ideology all its own, his approach has met forceful critique.

What we can learn here has nothing to do with Young Thug the man and everything to do with what he symbolizes. In our own age, we are asked to work out how one lives as a Christian in a post-Christian age; we are responsible for re-articulating what precisely makes a relationship, inside a community, with Jesus Christ so radically different from living as a secular human being. That synthesis has never been a question of running away, but it has always involved oddity, play, and affirmation of our very difference. That, it seems to me, is our way forward; our road is critique, not capitulation, re-readings of Perpetua, not defenses of normative authority.