Like most people I woke up today to horrific news: the murder of more than 50 people at a queer nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Perhaps unlike most people, I was not particularly interested in the biography of the perpetrator, his story, his motivations. Evil had become an anonymous force, a faceless god of chaos, not one man, a shooter driven to hellish deeds.

Instead, I felt desolate—a sense of total misery, an acute awareness of my own sins, and of the precariousness of life itself. I felt fully awakened to the perpetuity of evil in our world, in acts big and small.

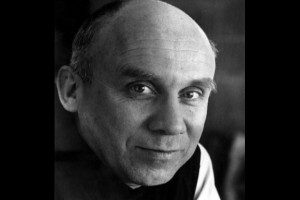

After sitting, paralyzed, for a bit, I slunk out of bed, went downstairs, and picked up one of the books I am reading at the moment: Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain. Fittingly (providentially), I came across the author’s thoughts on evil, his reflections on the decadence and putridity of the interwar world. Though nothing can provide permanence of comfort, his words resonate with the depravity of our moment:

It is only the infinite mercy and love of God that has prevented us from tearing ourselves to pieces and destroying His entire creation long ago. People seem to think that it is in some way a proof that no merciful God exists, if we have so many wars. On the contrary, consider how in spite of centuries of sin and greed and lust and cruelty and hatred and avarice and oppression and injustice, spawned and bred by the free wills of men, the human race can still recover, each time, and can still produce men and women who overcome evil with good, hatred with love, greed with charity, lust and cruelty with sanctity. How could all this be possible without the merciful love of God, pouring out His grace upon us? Can there be any doubt where wars come from and where peace comes from, when the children of this world, excluding God from their peace conferences, only manage to bring about greater and greater wars the more they talk about peace?

We have only to open our eyes and look about us to see what our sins are doing to the world, and have done. But we cannot see. We are the ones to whom it is said by the prophets of God: “Hearing hear, and understand not; and see the vision, and know it not.”

There is no flower that opens, not a seed that falls into the ground, and not an ear of wheat that nods on the end of its stalk in the wind that does not preach and proclaim the greatness and mercy of God to the whole world.

There is not an act of kindness or generosity, not an act of sacrifice done, or a word of peace and gentleness spoken, not a child’s prayer uttered, that does not sing hymns to God before His throne, and in the eyes of men, and before their faces.

How does it happen that in the thousands of generations of murderers since Cain, our dark bloodthirsty ancestor, that some of us can still be saints? The quietness and hiddenness and placidity of the truly good people in the world all proclaim the glory of God.

All these things, all creatures, every graceful movement, every ordered act of the human will, all are sent to us as prophets from God. But because of our stubbornness they come to us only to blind us further.

“Blind the heart of this people and make their ears heavy, and shut their eyes; lest they see with their eyes, and hear with their ears and understand with their heart and be converted, and I heal them.”

We refuse to hear the million different voices through which God speaks to us, and every refusal hardens us more and more against His grace—and yet He continues to speak to us: and we say He is without mercy!

“But the Lord dealeth patiently for your sake, not willing that any should perish, but that all should return to penance.”

Merton’s words struck me; they are apt. The knowledge of God’s love does not immediately fill the desolate void such violence kindles in the soul; and yet, the slow salve of their comfort provides a chilling reminder: every evil deed resounds loudly, but the good sing before the throne of Heaven.