Pope Francis mystifies—and aggravates—many Catholics; his talk of mercy, of suspending judgment has a tendency to attract charges of ambiguity, to draw ire from those who prefer the steady hand of a John Paul or the theological acumen of a Benedict.

In short, Francis is a true servus servorum Dei—clearly more comfortable advising than, well, pontificating. This has its obvious drawbacks—drawbacks which have been both rightly clarified and examined and which have also elicited scrutiny so intense that one is reminded of Jesus and the Pharisees. His emphasis on the pastoral belies a man less comfortable as a teacher and more as an adviser: slow to speak categorically, quick to suspend judgment.

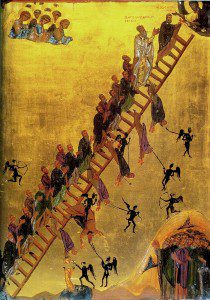

In reflecting on his pontificate I am reminded of a little known saint: an “Uncondemning Monk,” commemorated by both certain Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Christians. Notoriously remiss when it came to his duties, this monastic had but one redeeming quality: his absolute faith in the path of non-judgment, his commitment to listening before speaking. His story is found in the Prologue of Ohrid:

This monk was lazy, careless, and lacking in his prayer life; but throughout all of his life, he did not judge anyone. While dying, he was happy. When the brethren asked him how is it that with so many sins, you die happy? He replied, “I now see angels who are showing me a letter with my numerous sins. I said to them, Our Lord said: `stop judging and you will not be judged’ (St. Luke 6:37). I have never judged anyone, and I hope in the mercy of God that He will not judge me.” And the angels tore up the paper. Upon hearing this, the monks were astonished and learned from it.

Some might say this sounds like presumption. To me, it is reminiscent of St. Paul:

Love is patient, love is kind. It is not jealous, [love] is not pompous, it is not inflated, it is not rude, it does not seek its own interests, it is not quick-tempered, it does not brood over injury, it does not rejoice over wrongdoing but rejoices with the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. (1 Corinthians 13:4-7)

“I have never judged anyone, and I hope in the mercy of God that He will not judge me.” This is love, if I have ever seen it. Note that the story does not say that the monk never advised others, nor that he never spoke negatively of another. It merely says that above all he placed his hope in the infinite mercy of God.

Pope Francis feels similarly:

[The penitent] ought to reflect on the truth of his life, of what he feels and what he thinks before God. He ought to be able to look earnestly at himself and his sin. He ought to feel like a sinner, so that he can be amazed by God. In order to be filled with his gift of infinite mercy, we need to recognize our need, our emptiness, our wretchedness. We cannot be arrogant.

The path of this pope may not be for all; it may even cause discomfort to many. I merely contend this: Francis’ vision of the teacher as the listener, of the Christian as he who hopes in love, might be a timely corrective to our vision of the faith. The animosity his very lifestyle elicits is, perhaps, the clearest argument for this hypothesis.

Our pope is not perfect; for some, his way might even present itself as a challenge, a corrective too far in one direction. Perhaps.

But let no one say that his conception of the faithful Christian lacks anything in ancient authority. Let no one harden his heart so that he cannot, like the monks in the story, be “astonished and learn[…] from it.”