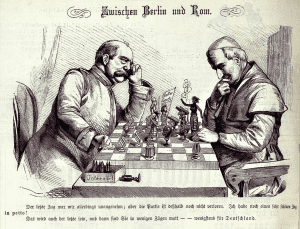

A piece online today at the Washington Post links “liberal” theology to declines in church membership while observing the opposite trend in “conservative” congregations. In it, the author, David Millard Haskell, presents his research as overturning older theories that “getting with the times” might revivify religious life in the 21st century:

For example, we found 93 percent of clergy members and 83 percent of worshipers from growing churches agreed with the statement “Jesus rose from the dead with a real flesh-and-blood body leaving behind an empty tomb.” This compared with 67 percent of worshipers and 56 percent of clergy members from declining churches. Furthermore, all growing church clergy members and 90 percent of their worshipers agreed that “God performs miracles in answer to prayers,” compared with 80 percent of worshipers and a mere 44 percent of clergy members from declining churches.

In other words, clergy who believe in the traditional dogmas of Christian faith are likely to build more orthodox (and larger) congregations while those who reject the basics of Christianity are more likely to build smaller, less orthodox ones. Many have made similar points before, though some liberal Christians have disputed their conclusions. What this research suggests is that mitigating factors like lower birth rates and a lack of church planting are not the primary causes of decline: theological liberalism is.

The study only seems to deal with Protestant groups. Many Catholics, however, are likely to see Haskell’s work as vindication of American, conservative Catholicism, that is, for a return to a more conservative (in the American political sense) liturgy and theology. This view is not, per se, wrong, but it might move to judge too quickly. We must ask ourselves what “liberal” here really means and see how that maps onto Catholic belief and practice (I will not address the question of liturgy here, since that does not seem to have been an aspect of the research).

Liberal Protestantism does not just mean all post-Vatican II theology, bad liturgy, or women priests. The term is much older and predates the contemporary decline. Its development occurred in stages from the hermeneutical analyses of Schleiermacher through the early-20th-century works of John Oman. The key term uniting these different historical instantiations is “liberal.” “Liberal” here does not mean pro-government or pro-choice. No, it means—as I have argued before—rooted in the Enlightenment with a particular emphasis (and this is a generalization) on individualism and private experience. Liberal theology—whether pietistic or rigorously historical and critical—finds its roots in post-Enlightenment philosophies of the person, time, and society.

This distinction is important, because it implies that social justice is not the problem, concentrating on the suffering of others is not the problem, believing in the power of the Church to transform the world is not the problem. In fact, based on this definition, one could argue that the theologies and politics of “conservative” American figures like John Courtney Murray are far more “liberal” than the Leftists political theologies of Herbert McCabe and Gustavo Gutiérrez. One can have tradition-rich theology without reverting to what we term “conservative” (though actually quite liberal in the original sense) thought. To put it simply: the option for the poor is more likely to find deep resources within the Tradition than atomized theories of charity or individual freedom, both center-Right and center-Left.

The difference, then, and what “liberal” really means here is “failure to hold orthodox beliefs about Christian dogma.” Haskell says as much:

For example, because of their conservative outlook, the growing church clergy members in our study took Jesus’ command to “Go make disciples” literally. Thus, they all held the conviction it’s “very important to encourage non-Christians to become Christians,” and thus likely put effort into converting non-Christians. Conversely, because of their liberal leanings, half the clergy members at the declining churches held the opposite conviction, believing it is not desirable to convert non-Christians. Some of them felt, for instance, that peddling their religion outside of their immediate faith community is culturally insensitive.

Put simply: is your desire to transform the world rooted in a deep and rich theological tradition or is that tradition merely a veneer or justification for doing what you would otherwise do (feed the poor, clothe the homeless, etc.)? Going to a school attached to a liberal seminary, I have seen some of this. The seminarians around me are often very intelligent people, well trained in how to read the Bible, and aware of every historical contingency in its development (and these things are important!), but it is sometimes unclear exactly how Christianity relates to their desires to help God’s people. One student’s slippage during class was indicative. When speaking about what churches ought to do post-Trump (and I’m paraphrasing), he commented that he was happy to have been told that people are finding meaning in activism, seeing activism as their religion; it creates a sense of purpose and belonging in a time of marginalization. This is not the impulse to evangelize, nor is to likely to set the world on fire. Rather, it seems to put philosophical and political commitments over and above theological ones (he is, I should add, clearly a deeply-concerned and smart guy).

Fittingly, his story was followed by that of another classmate, a liberal Protestant, who praised the actions of a Catholic bishop she had seen while attending a Mass, commemorating the closing of the recent Jubilee Year. What had he done? He had used his role as bishop to commemorate those currently in prison—an effective unity of socio-political concern and traditional authority.

Such is the crux of the thing: do we do good because we feel formed in Christ or does Christ merely stand behind a tradition (one of many) that might justify our desire to act on others’ behalves? Catholics would do best—conservative and liberal in the American sense—to ask themselves this. Haskell’s research is not necessarily a vindication of American conservatism, but a cry to root ourselves deeply in Tradition, the joyous Tradition that sees the poor and the broken, that transforms the world, because of and through the God-man, Jesus Christ.