Silence might be the most Catholic thing I have ever seen. To truly justify that, I’d need to spoil the film. I won’t, but I’ll say what I can, try to express its impact on me without reflecting the content of the images I saw.

I have not read Endo’s novel, though I’ve heard about it many times along my journey to the Faith. The decision of the (at minimum culturally) Catholic Martin Scorsese to direct its film version excited lots of Christians I know—what could go wrong when you combine Catholic sensibility, rich subject matter, and one of the most successful directors in the history of cinema?

Not much. Except perhaps that I found it nearly impossible to watch as a film. I’m typically swift to notice the flaws and triumphs in movies; I’ve developed (at times to my detriment) a certain objective distance from the subject matter at hand, partly because I’m currently working on a movie myself. With Silence, this was utterly impossible. I cannot imagine a Catholic watching the film and not shedding tears. I saw it projected digitally in a New York City mega-theater, hardly the perfect environment for cinematic purity, and yet I was entranced. The film tortures the viewer just the same as the Japanese tortured their island’s secret Christians. Tears abounded in the first half, but simply wouldn’t come after hours of on-screen physical and psychological erosion. By the end, exasperation seemed the only valid reaction. When the credits began rolling, my friend and I could do little but sit in silence.

The only other film I can recall putting me in a similar state is a movie I can only describe as emotionally manipulative, like an atom bomb for the psyche: Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies.

But that lacked the Catholic connection. Silence sounded a call to live, to take up my cross, so much so in fact that I found myself gripping my own crucifix necklace at moments of special temptation and grievousness. It’s that timelessness that really affected me; it’s that timelessness that begs me to put away any cinematic squabbles (and I have a few) to review the film without spoilers.

I know many people know Endo’s work well; others have an investment in locating the story historically, reminding us of the particular horrors faced by Japanese Christians. I understand that. As a youth, I was slightly obsessed with feudal Japan; the cultural issue cannot be ignored.

And yet, at the center of the film are long-lasting historical conflicts. At times, one feels as if Scorsese made the anti-Christian Japanese elites comically evil; their willingness to discriminate, equivocate, and torture (would that such torture were only physical!) without ever giving a real reason cannot help but disturb. In other words, the good guys are never ambiguous. We may not always like the missionary priests; we may not always agree with their actions, but they are clearly (though stained and broken) not the forces of darkness in the film. Morally ambiguous and sinister are two separate categories.

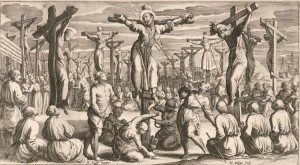

Parts feel like a replay of the battle between late-antique paganism and Christianity. Silence rarely shows us Japanese folk religion; instead what haunts the priests day-in and day-out is the specter of an elite philosophical system, an established, ethnocentric belief in hierarchy, nature, and obedience. We see few altars, few Shinto or Buddhist priests; instead we witness conversations—disputations if you like—between Catholics grasping at transcendence and Japanese elites defending the need to harmonize oneself with this world, this nature, alone. What is nature? What is man? Can god be a human being? For these questions, voices have gone and will go hoarse and bodies have and will bleed.

Although today such discussions are rare, their historical representation in the film has meaning for Catholics today. The torture and death of illiterate peasants reminds us of both our historical suffering as a pilgrim people and our need to be willing to continue to do so. The last thing Scorsese protects is bourgeois individualism and contemporary comfort; the film screams, echoing: eli eli lama sabachthani! The clash of philosophies points backward to past persecutions and forward to the ongoing push to envision transcendence in the world, not to succumb to the “natural” philosophies of the age, but to always remember that our world itself is enchanted with God’s grandeur, a grandeur we help manifest in our works and deeds of Christ-like, bloody, long-suffering love.

Some people will reduce the film to its context or to the question of apostasy-salvation. These are integral to Silence; no one can deny that. And yet, most of the film is not about apostasy, but torture and faith. It all takes place in Japan, but we see different sides of the island: the xenophobic, half-pagan elite and the well-meaning Christian bumpkins. The film is not simply the tale of an island divided, but of a world fractured, a testament to the trans-historical mission of evangelization and suffering, of hope and silence.

See it.