Source: Flickr user Jamie

License

When Kubla Khan did his stately pleasure-dome decree, I imagine his court was excited. Dancing? Zithers? Wine? What’s not to like? I have trouble seeing Kubla or one of his Sinicized Mongol courtiers looking dour: “no. I already watched the dancing girls today! I want new dancing girls! And wine from Shanxi, not Hebei! And the goose stinks! Have the chef executed!” Maybe it happened that way, I don’t know. But life in the saddle ain’t easy. Seeing half your family dead from now-treatable illnesses has to do something for the taste of wine and touch of fine silk, right?

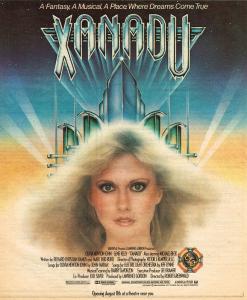

America, especially today, is a bit different. I couldn’t shake the comparison as I watched Xanadu (1980), a movie intended to be lush and stimulating, even as it falls flat on its face. Inured to pleasure by cell-phone stimulation and limitless streaming, was my anhedonia the problem? Was it all the gray drabness in which we all “live”? Did the bright color and early CGI bounce off me like oil poured on a wet fish because I’m a joyless last man? Or was it the culture that produced the movie that went wrong? Had even Gene Kelly lost the pep in his step, standing athwart history yelling “stop”?

Xanadu is an odd duck. Sticking Olivia Newton-John as the Greek Muse, Terpsichore, next to a humdrum commercial painter named Sonny Malone (Michael Beck), the plot is thinner than Kate Moss in the early 90s. Sonny teams up with an old clarinetist to open a fusion 40s-80s nightclub (naturally, called Xanadu). It turns out Newton-John had previously been Kelly’s muse, way back in the day, though now she’s confounded by true love for a mortal (Beck). That doesn’t really go anywhere, though. Xanadu is musical numbers all the way down. Even the bizarre wipe cuts and manic screen fragmentations feel like little more than ways to drag us into the next song-and-dance routine.

And you know what? Many aren’t bad. I admired Xanadu’s gumption. The movie tries to entertain in a way I haven’t seen in a long, long time. It barrages the viewer with costume changes, floating stages, roller-skate whirlwinds, and tap routines. I couldn’t help but smile when a person in full cat make-up crept through the legs of a row of ballerinas in spider-web nylons. It may only hit the ball about 15 feet, but Xanadu shoots for the fences. The film’s utter bizarreness commends it.

It remains, however, a mess. Many of the routines are shot at eye-level and straight on. We rarely see the full scope of the dancing; things often just look crowded and unbalanced. At one point, Newton-John shifts through four or five different song and costume changes within about three minutes (rock, new wave, country, and swing—if I recall correctly). None of this has any obvious relationship to the emotional center of the scene (Xanadu opening? Her love for Beck?). Only Kelly’s zoot-suited moves offer occasional consolation.

Still, the movie tries so hard. It still wants to please in a way that rarely strikes me when watching contemporary blockbusters. You can tell how magical the crew found the early CGI and set work. Xanadu even has a full-on, old-school animation sequence, one that looks worthy of Disney (and I’m talking the good stuff!). At bottom, the film wants the audience to have fun; even if fails, its desire is to entertain, and it will go to whatever lengths necessary to succeed.

Thinking it through, I suspect my own anhedonia may be the issue, though the movie shows signs of the pastiche-driven hyperstimulation that would end up producing people like me. Xanadu was a sign of things to come, but it knew not where life was headed. I’ll take the blame for this one.