The story is necessarily—like this season—one filled with sadness and joy. In 1549, St. Francis Xavier arrived in Japan. Two years later he and his associates departed, leaving behind quite a few converts. Their point of arrival—the Japanese island of Kyushu—has remained the hub of Japanese Christianity ever since. Whatever their successes (and it should be noted that Kyushu is not the main island in Japan—one might compare it to England’s place in Europe), the Japan they found was in a state of turmoil, and a need for national unity would soon turn the Faith into an easy (and, from the perspective of the land’s leaders, understandable) scapegoat.

This period in Japanese history is known as Sengoku Jidai, or “the Age of Warring States.” In essence, there was a crisis of authority. For much of medieval Japanese history, there was a shogun, that is, something like a generalissimo. The title has military roots, and initially meant a specially-selected commander, whose role was fighting barbarians (while Japan is fairly ethnically homogeneous, it is home to minority groups). Over time, it came to refer to the ruler of Japan, the one who handled the day-to-day affairs of state while the emperor came to take on a more ceremonial function. By way of comparison, one might (though this is not a perfect analogy), think of the emperor and the shogun as the contemporary queen and prime minister of the UK. By the beginning of the period in question, the centralized authority of the shogunate had begun to falter; civil war ravaged the land.

To abridge a long and fascinating history, several figures rose up and consolidated power just as Christianity became more influential in Japan. First Oda Nobunaga, then Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and finally Tokugawa Ieyasu took the reigns of state. Only the last of these—who gives his name to the famous Tokugawa Shogunate—fully managed to secure control over the entirety of the country. Ailing Japan needed unity and the Tokugawa were ruthless about enforcing it. Many local warlords were stripped of their power (either for opposing the new regime or under various pretexts. As a total side note, check out Kobayashi’s phenomenal 1962 film Harakiri on just this topic). The class system was solidified as peasants were kept from doing anything besides agricultural labor (a nice irony, since Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of Japan’s unifiers, was born a peasant).

To the Shogunate, Christianity was an obstacle to unity, a foreign virus with nothing to offer Japan but destabilizing colonial influence. This fear was reinforced by the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-1638, in which Japanese Catholics rose up against unjust social conditions. In a weird twist of fate, the Shogunate called in the Dutch to help quell the rebellion:

The revolt began as a result of dissatisfaction with the heavy taxation and abuses of local officials on the Shimabara Peninsula and the Amakusa-rettō Islands. Most of the peasants in the Shimabara vicinity had been converted to Catholicism by Portuguese and Spanish missionaries, and the rebellion soon took on Christian overtones. With the support of large numbers of rōnin, samurai whose lords had been dispossessed, the rebels fought so zealously that an army of 100,000 troops was unable to quell them, and the Japanese government had to call in a Dutch gunboat to blast the rebel stronghold. Following this incident the government vigorously enforced its proscription of all Christian beliefs and activities. (Encyclopædia Britannica)

This put the final nail in the coffin for Christians in Japan. Starting in 1633 (and enforced more stringently after the rebellion), Japanese subjects were forbidden to travel abroad or to return home, and trade was limited to a few Dutch and Chinese merchants in Nagasaki. The country entered a state of near-total seclusion and Christians began to be persecuted mercilessly.

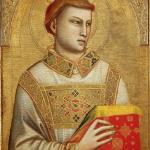

It is this turn of events that Silence witnesses; it is the Tokugawa Shogunate’s totalizing desire for stable authority that led to the deaths of thousands of Japanese Catholics and missionary priests. Not too long before there had been quite a few Christian or Christian-friendly daimyo (perhaps think of them as medieval European counts or dukes), samurai (more-or-less knights), and other nobles in Japan: Otomo Sorin, Mancio Ito, Chijiwa Migeru, Nakaura Jurian, Hara Maruchino, Omura Sumitada, Arima Harunobu, Date Masamune, Blessed Justo Takayama, Hasekura Tsunenaga, Hosokawa Gracia, and Kuroda Yoshitaka, to name but a few. These were now all gone, and the common people suffered for it. Anyone who has seen or read Silence knows something of their travails:

By the 1640s, not a single priest was left in the whole of Japan. Christians in Nagasaki realized that if they, too, were to die as martyrs, the Japanese church would die with them. As persecution raged and the prospect of the Christian faith’s complete eradication from Japan became imminent, these Christians made a decision that was to have dramatic consequences over two centuries later: to continue their faith in secret.

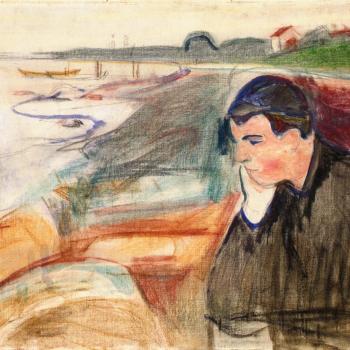

The story of the underground church is one of suffering. Throughout the ban on Christianity in Japan, people in Nagasaki were required at an annual ceremony to trample on an image of Christ or the Virgin Mary, known as a fumie, to prove they were not Christian. These ceremonies haunted the imaginations of the secret Christians, who were without priests to absolve them. Every year they would creep home and utter penitential prayers, begging God to forgive them for what one scholar has called “this most necessary of sins.” (The Japan Times)

Their immense suffering should not—cannot—be forgotten.