Did Trump win because of the dissatisfaction of the working class? Some say “yea”; some say “nay.” Opinions abound and it’s dizzying. In spite of this vortex of thoughts (also known as the internet), I was struck by a friend’s recent tweet, baldly asking how we (especially those of us who are Christians) can say that workers as such got Trump elected. He wanted to know how, when he knows so many wealthy or middle-class Christians who croon on about Trump’s support by the poor, we can really keep believing this? Is the working class just a justification, ushered by his wealthier supporters?

I confess that, being from a white family of working-class background, I have often found it hard to deny that Trump has some appeal to such people, but I can’t help but feel moved by his challenge. How can we explain Trump’s support by better-off Christians?

For starters, my friend was responding to a piece by First Things’ Matthew Schmitz (whom I also know). Schmitz draws on an existing family model to try and explain religious, working-class support for the president. Red families tend to be hierarchical and prize fertility and rectitude. Blue families tend to prize equality and companionship (but care less about fertility). Both, he says, are unlikely to find Trump palatable because he violates their politics of respectability. To one group he’s objectifying, a misogynist; to the other, he’s unrighteous, even immoral. Schmitz adds a third group, more likely to support Trump: purple families.

A third model can be found among working-class whites, blacks and Hispanics — let’s call it purple. In these families, bonds between mothers and children are prized above those between couples. Unstable relationships are the norm, and fathers quickly end up out of the picture.

The difference among these three family models explains three different reactions to Mr. Trump’s candidacy. Liberal professionals decried his sexism, which violated the prime value of the blue family model: equality. Elite evangelicals decried his infidelity, which ran counter to the red family model’s stress on fidelity.

He goes on to argue that such purple families tend to be Baptist, Evangelical, and/or Pentecostal, hence the president’s support among these groups. This then is supposed to explain his popularity with the “religious working class”—they’re simply more understanding of his family life:

Baffling as it may be to elites, Mr. Trump embodies a real if imperfect model of family values. People familiar with the purple family model tend to view his alienation from his children’s mother as normal and his closeness to his children as exceptional and admirable. I saw this among my acquaintances in Nebraska. Even those from red families were more likely than my acquaintances in New York to know someone who has had a child out of wedlock or is subject to a restraining order.

On the one hand, I’m sympathetic to Schmitz’s point: I know plenty of people who fit the sort of model that he’s talking about—people who are far from doctrinaire conservatives, but who have some (often nostalgic) notion of propriety, tempered by hard lives and a variety of social and individual misfortunes. On the other, I can’t shake Nathan’s: what about this is working class (there is, after all, decent proof that Trump’s support among wealthy whites helped him win)? How can we call this “religious” if it doesn’t care about morality or faith? Can “family models” really be used to explain something this complex?

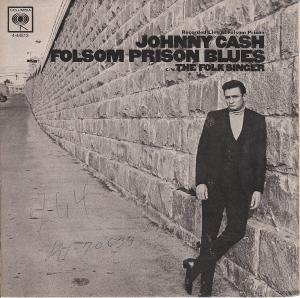

I can’t say I have an answer, but I do have an idea, one I think worth exploring: the history of folk and country music. A little dive into the past may help to explain how the working class gets used by elites to explain things, and how, on occasion, it’s fought back. There may be, as we shall see, a lesson about Trump and religion in all this.