Why? Folk and country have always been “popular” music, though not in the way contemporary “pop music” is. Their origins lie in the people, as expressions of discontent, culture, tradition, and unrest. Martha Bayles has the following to say about the ultimately and continuingly political purposes of this “music of the people”:

The appropriation of folk music for political purposes dates back to mid-nineteenth-century Europe, where folk songs became a means to express nationalist sentiment. During the twentieth century, European ideologues across the political spectrum laid claim to the music of the folk. In Germany the left created many highly political songs based on folk music, and so did the right. Indeed, when the Nazis came to power in 1933 they put the folk song, or Volkslied, at the center of their public spectacles celebrating the superiority of the “Aryan” race. They also, in process, poisoned the well for future generations of German folkies. (As one young Berliner said to me a few years ago, “Around the campfire we sing mostly American songs.”)

Communist regimes took similar advantage. From the 1930s forward, folk music was exploited as a way of defining—and controlling—the various “republics” making up the Soviet Union. In the 1970s the American ethnomusicologist Theodore Levin traveled in Central Asia to observe this ongoing process. While Levin found a subterranean musical life that was “complex, alive, and intimately linked to the innermost lives of people,” he also measured the gap between that and “the glitzy professional folk troupes that became the official cultural ambassadors of the Central Asian republics.” One aspect of the gap was the elimination from official folk music of all religious references.

No one on the American left ever manipulated folk music on such a grand scale. But most labor and other activists believed that music was very important. As Mike Gold of the Daily Worker wrote in the early 1930s, “Songs are as necessary to the fighting movement as bread.” The only question was, which songs?

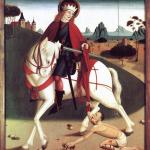

As far back as the Middle Ages, folk music was used to political purposes, because wherever there is the expression of their poor there is necessarily something social, some cry—call it conservative, liberal, progressive, or whatever else. The Tale of Gamelyn, for example, dates from the late-medieval period and tells the tale of an outlaw named Gamelyn, who fights a corrupt system by retreating into the forest. There is, of course, also Robin Hood, also Adam Bell. Slave songs in the Americas are, of course, a familiar, and important, addition to the point. Outlaws, resistance, and—if I may call it this—popular spirit have always pervaded folk, from early ballads to bluegrass.

In fact, a recent piece in Current Affairs, traces the evolution of the trucking song (and of trucking more generally) from something dominated by union people and avowed workers to something substantially more conservative, opposed to the norms for which it once stood:

The nature of the American workplace is such that you’re unlikely to get paid a living wage to do something pleasant and engaging for eight hours a day. In trucking, the reality is a bit more extreme. The once-popular trucker music vividly described truckers’ long hours and exhausting lifestyle long before it was national news. A driver in Joe Maphis’ “Ten Days Out, Two Days In” complains that:

“I’ve had to drive ‘em every night and day just to make enough to pay my bills / Lately I’ve been seein’ two of everything and I ache from my head to my toes.”

A long-haul trucker in the 1970s could expect to work over 60 hours a week (exact numbers are hard to come by, since drivers rarely record their hours accurately), including time spent driving, loading, unloading, making repairs, and filling out paperwork. He’d usually end his 10-, 12-, or 16-hour day far from home and crawl into bed in a sleeper cab. Hence Maphis’ complaint that “I kiss my baby and I’m gone again…. My old dog bites me every time I come home…. I came home today, heard my little boy say, ‘well mama, who is that man?’”

Grueling hours and strained relationships aren’t unique to trucking. What’s most remarkable about “Awful Lot to Learn” and its ilk is hearing these realities depicted in a mass-market radio hit. Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, popular music has studiously ignored the time its listeners spend working for a paycheck. Even the rawest of country music typically takes place in homes, hollers and honky-tonks. The trucker subgenre stands out as unique for being set in a workplace—the cab of a truck. During the decade and a half that trucker music made its mark on the country-western airwaves, it offered listeners a portrait, albeit romanticized, of the perils, frustrations, and petty triumphs of life on the job.