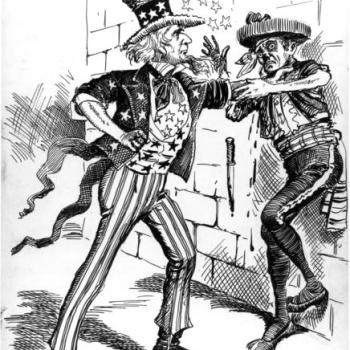

There is good reason to fear the nation’s becoming an idol. In fact, the idol of the American nation was often used against Catholics, who it was thought would hand the country over to the pope. We were also suspect on racial grounds:

It was never easy to separate the racial and religious components of anti-Catholic sentiment. Until the 1920s, America’s doors were open to European immigrants, as long as they qualified under a statute passed in 1790 that reserved naturalized citizenship for “free white persons.” Whether Southern and Eastern Europeans of darker hue—or all Catholics, whose presumed loyalty to Rome rendered them suspect candidates for democratic citizenship—qualified under the statute, seemed very much an open question.

As the immigrant landscape grew more complicated in the late 19th century, social scientists and politicians began attempting to classify Americans with greater precision. Whit[e]ness, it now seemed, was a matter of degree, and Europeans fell into categories like “Anglo Saxon,” “Celtic,” “Hebrew” and “Asiatic.” Importantly, this move toward racial classification drew heavily on the emerging fields of modern biology and chemistry. In this sense, modern science and social science were contemporaries—and close cousins—of modern racism.

In 1911 the famous Dillingham Commission on Immigration attempted to reduce the mass of new immigrant groups to a simple five-tier racial scheme (Caucasian, Mongolian, Ethiopian, Malay and American). But it wasn’t always so simple. In Volume 9 of its lengthy report, otherwise entitled A Dictionary of Races or Peoples, the commission backtracked and acknowledged that the U.S. Bureau of Immigration “recognizes 45 races or peoples among immigrants coming to the United States, and of these 36 are indigenous to Europe.”

Critically, many scientists and social scientists (the Dillingham Commission experts among them) agreed that race was determinative of behavior, intelligence and physical endowment, and that racial groups could be arranged in a hierarchical fashion. The Dictionary of Races or Peoples, for instance, characterized Bohemians as “the most advanced of all” Slavic race groups. The Southern Italian, on the other hand, it deemed “an individualist having little adaptability to highly organized society.” (Politico)

The thing is we do owe loyalty to God (and the successors of His Apostles, the bishops) before we owe anything to our country. This does not, of course, mean there is no room to serve one’s country under any circumstances, but it does mean that, on the non-racial level, there is a sense in which we were subversives. Perhaps we could learn from this: American nationalism was turned against us, ought we not be suspicious of it? Ought we not be reticent to turn it against anyone else?

Some might say: “so what? We helped to expand the definition of religious freedom. That’s a good thing! We should appreciate the struggle and its fruits!” This may seem a convincing argument. It, however, relies on the idea that “religious freedom” is what we were striving for. On the one hand, one might cite Pope Pius IX’s “error has no rights” from his Syllabus of Errors (he did not use quite those words, but they have caught on regardless). We may put this aside, however, for it is complicated, perhaps too much so for this blog post. More importantly, there is a pragmatic sense in which “religious freedom” presents a problem.

This term implies a mediated pluralism: we live in a liberal democracy where the state must carve out the niches in which religion is free to act. The problem is the woeful inadequacy with which the concept has acquitted itself. Never mind the famous baker case: there is the issue of circumcision among Haredi Jews in Brooklyn, the banning of circumcision in Iceland, and the bevvy of problems religion has faced in places like Kemalist Turkey. Has the difficulty of negotiating along these lines not played some role in the recent Ahmari-French debate? Admittedly, not all of the issues I note took place in the US; many did not. That said, it is clear that the concept of “religious freedom” is far from a guarantee of Catholic survival in the US. I do not, of course, mean that I think we will face persecutions (nothing of the sort); I do, however, believe that too many too easily wave away the tension between our faith and our country with this magic formula.