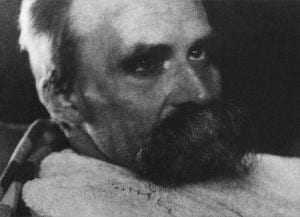

A student followed me out of class the other day; he couldn’t believe that I, a Christian, could find Nietzsche edifying, let alone that I kept a painting of him catty-corner from my icons. Around the same time, a Twitter friend asked me much the same question: why look to Nietzsche for faith?

My answer is necessarily a personal one—that’s all it can be. What has Friedrich Nietzsche to do with Jesus Christ? The pairing seems impossible, and yet, for me, it has been fundamental—dare I say, essential.

Ironically enough, the best place to start might be The Antichrist:

Nihilist and Christ: They rhyme; they do not merely rhyme.

This is shocking. Is the Christian not the opposite of a nihilist? Does he or she not believe in something, perhaps the grandest something to ever give meaning to life: a god-man, a sacrificial victim who saw greater purpose in death and resurrection, in suffering and abjection, than in comfort and aimless hedonism? How much odder, then, to say that Jesus Himself was a nihilist. Not just the fruit but the root itself signifies a denial of meaning, of the possibility of significance.

Nietzsche knew this would be shocking; that’s one of his primary ways to, as the crunchy Leftists of the 90s might have put it “wake people up.” He believed this to be true, because he believed Christianity to be too pie in the sky. We need only look at the lines immediately preceding the ones cited above:

This was his [Paul’s] revelation at Damascus: he grasped the fact that he needed the belief in immortality in order to rob “the world” of its value, that the concept of “hell” would master Rome—that the notion of a “beyond” is the death of life. (The Antichrist)

Christianity asks us to live up to “ideals,” to abstract principles greater than ourselves, beyond ourselves, things we must necessarily fall short of. He’s not wrong: we imply this with our treasured word “grace.” For Nietzsche, this makes the Christian a hypocrite, one who denies life its vitality by imagining that the truth of life lies outside its finite bounds. Christianity glorifies self-effacement, poverty, and sacrifice—notions that gut life of its—for him—intrinsic verve. Christ is thus the most nihilistic of all. He voluntarily hands Himself over to die in the name of life-giving death. In doing so, He become the paradigm for Christian belief and practice. Essentially, Jesus stands as the hypocrite who teaches all others to fall short, to hope in the unseen, to destroy life in the name of a supposed life-beyond-life.

Nietzsche’s alternative is the embrace of life itself, the doing-away-with of all such idealistic pretensions, the, as he puts it, “revaluation of all values.” Rather than assuming some inherent morality to the universe, one that we must discern and, by grace, try to live up to, he prefers that we embrace life itself in a constant process of overcoming, always destroying what we have been only a moment earlier to become something greater, something stronger. If Christianity leads to hypocrisy, this, at least, leads to a kind of sincerity, a full embrace of the vicissitudes of lived experience, refusing to cave in, to do anything but live.

There is an honesty here. If one’s true fulfillment comes in—to choose an extreme example—murdering children, then so be it. There can be no intrinsic prohibition on such a thing. We other people might argue that such a drive is unhealthy, that it couldn’t possibly be based in anything but resentment, but we can’t in principle rule it out. Each person is different; each person’s process of self-overcoming will thus be different. Embracing life qua life means constant self-destruction, which is a kind of giving birth. All things are permitted, at least in theory. Hence, Nietzsche writes:

I am, for instance, in no wise a bogey man, or moral monster. On the contrary, I am the very opposite in nature to the kind of man that has been honoured hitherto as virtuous. Between ourselves, it seems to me that this is precisely a matter on which I may feel proud. I am a disciple of the philosopher Dionysus, and I would prefer to be even a satyr than a saint. (Ecce Homo)