Source: Wikimedia

License

Elmer Gantry (1960) is an easy movie to reduce to one of its elements. You could fairly easily see it as a straightforward critique of organized religion, some avant-garde assault not just on today’s blatant televangelists and cult leaders but on the whole of faith as such. You could just as simply call it a saccharine bit of old-fashioned wisdom literature, a film only a step or two removed from shlock like Reefer Madness (1936). It is indeed moralistic and critical of “revivalism.” It features literal miracles and obvious Marjoes. Yet, neither of these facts says much about the movie.

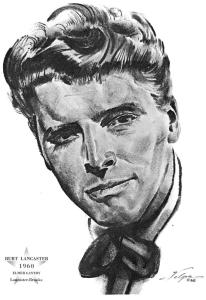

We follow drinker, smoker, and salesman Elmer Gantry (Burt Lancaster) as he hops trains, fails to visit his mother, and gives impromptu sermons at bars on Christmas out of the good of his heart. He shacks up with Sister Sharon Stone (Jean Simmons), a traveling evangelist whose tent revivals whip the farmers of the Midwest into frenzies. Will he corrupt her? Will she save him? Or—as you might guess—is the reality substantially more complicated?

Elmer Gantry draws us in with its compelling sets. Director Richard Brooks establishes a world of windy roadsides, smoky bars, and torch-lit riots, the sort of places in which early automobiles run up against farmers who look to subsist on nothing but dust and resentment. Men in suits pontificate before typewriters and deny the divinity of Jesus Christ while self-important sheriffs smash up bars and brothels in the name of temperance and Christian morality.

Lancaster steals the show as the titular character, his wide grin and easy manner are reminiscent of Cosmo Kramer. But that’s just it: his sly smirk is that of a conman but not merely so. His love affair with Sister Sharon drives the film—and he’s got to at least con us into believing he can change for the movie to work (and it does!). Sister Sharon is not all she seems either. We learn that this is a chosen name, a reinvention to allow herself full devotion to God (and to build a great, big church of course).

These ambiguities make for a number of topical scenes and moments: a fascist, torch-lit rally, sexual blackmail, urban-rural conflict, accusations of fake news, and battles over social mores. It makes one feel as if the US never changes (something the filmmakers must have believed themselves when they looked back to the 1920s from 1960). What makes Elmer Gantry feel fresh is that it confronts these difficulties without becoming polemical. It may be sentimental, but that’s a cheap price to pay for a kind of humanism. It imparts a strange hope—something I haven’t felt in a long while.