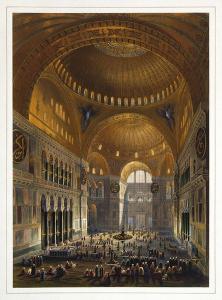

The Hagia Sophia is back in the news—this time because Turkey’s Supreme Court ruled that the church, turned mosque, turned museum, could once again be used as a mosque. This is—ostensibly anyway—a religion blog, or at least one mostly concerned with religion. The takes of the religious though, in my opinion, have missed the significance of this decision. The Russian Orthodox Church has expressed dismay. Many Christians I know see it as a victory for Islam over a beleaguered and disfavored Christianity. Turkish nationalists are, to put it mildly, pleased.

These are predictable and understandable reactions from all sides. But to lose the thread there, at the question of cultural or even aesthetic significance is to miss what’s really going on. The Turkey of today is not the Turkey of a century ago, nor is Erdogan a typical NATO ally. The Islam of modern Turkey is not the Islam that conquered Constantinople so many centuries back. To see only the cultural victory or loss is to miss what made such a thing possible; it is to surrender politics to the realm of the symbolic, missing the forest through the trees (as the saying goes).

Modern Turkey was born from the ashes of the once-ascendant Ottoman Empire. In fact, Constantinople was not renamed Istanbul until 1930; this was, contrary to popular belief, less about Islamifying the city than about Turkifying it. This new state was Wilsonian doctrine about national determination taken to its extreme. The country would officially be secular, banning, for example, head-coverings from places of public prominence. It, however, also exchanged basically its entire Christian population with Greece (taking in Greece’s Muslims as it sent away its Christians). The new Turkey would be secular in its government, yes, but it would also define a “Turk” as, in effect, a “Turkish-speaking Muslim.” Hence the need to call Kurds “Mountain Turks,” since their use of Kurdish set them apart from the broader population.

This may seem odd: why get rid of the Christians if you’re dedicated to secularism? We must remember, however, that sectarianism is never so simple as religion or ethnicity—it’s some combination of both, with questions of language and broader acculturation thrown in. Members of the IRA were not necessarily pious Catholics, nor were members of the UDA always committed Presbyterians. These identities are formed over generations, often having far more to do with how society sorts you, rather than how you would like to sort yourself. Thus the new Turkish nation could be officially—even at time viciously—secular, while ensuring that its population was Muslim (since here “Muslim” means “Turk” as much as anything else).

This brings us to Erdogan, Turkey’s current president. His headship has meant many things, but most of all it has meant the slow re-Islamification of the country, an attempt to strip away the official secularism of the its founding. “Muslim” should now mean “Muslim,” not something more ambiguous. He found a willing base in Turkey’ more rural population. As Gary Brecher has hinted, Turkey is the country with perhaps the most demographic similarity to the United States. Decades of dominance by the cosmopolitan coastal cities like Istanbul and Izmir (this might be analogous to the broad liberal consensus in America across the mid-twentieth century) had left the generally more religious, “red state” in-landers in search of a leader. They found one in Erdogan. The deal was really quite simple: he would make Turkey more economically and religious significant, build a sort of pan-Turkish coalition, and make the country, well, great again. They, in turn, would vote for him and end the cycle of military coups and coastal dominance that had obtained since the country’s founding. Some people call this ideology “Neo-Ottoman.” Maybe it is. Maybe it’s not. The most important thing is that, without understanding this deal, we cannot understand what is happening with the Hagia Sophia.