Forgive me, reader, for I have sinned—I’m reviewing another Kevin Smith movie, the one that, last week, I said a paragraph or two couldn’t explain. Turns out I still think what I thought almost seven days ago (crazy, right?) and I figure it’s about time to lay out why Chasing Amy (1997) is up there with Something Wild (1986) and Boys and Girls (2000) among my favorite of the post-Golden Age romantic comedies (that last one really, really requires some explanation—but another time. I can only justify myself so many times in one paragraph). But before I commence with summarizing the action, I implore you to stop reading if you haven’t watched it. I’m not exactly Captain Padusniak of the Spoiler Defense Squadron, but this is one that I think hits extra hard after an early twist.

Don’t say you haven’t been warned.

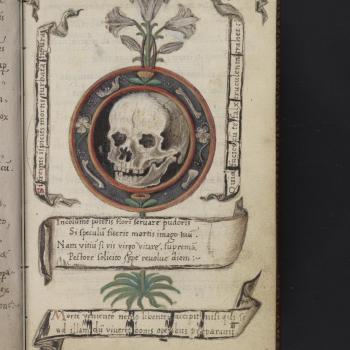

Abandon hope all ye who enter here without having seen the movie.

No trespassing.

Chasing Amy is about identity and the ways in which it’s projected, refracted, accepted, and rejected. We start off simply enough with comic book artists (or should I say “writer and inker”) Holden McNeil (Ben Affleck) and Banky Edwards (Jason Lee) at a convention in New York City where they participate in a staged publicity stunt for their friend and fellow author Hooper X (Dwight Ewell), a very gay man masquerading as a straight Black nationalist on the verge of a homicidal breakdown (complete with a pin reading “the Black Man is God”). Hooper introduces the pair to women’s comic artist, Alyssa Jones (Joey Lauren Adams). The group heads to a bar where Banky and Hooper soon duck out to buy Archie comics after getting into a fight about whether the titular character is gay. This leaves Holden and Alyssa some time to get to know each other; our young man is quickly smitten. Despite cutting the night short because he has to get back to New Jersey, our man is in luck—Hooper is tending bar the next night and asks him to stop by (“Alyssa will be there.” – Hooper “Alyssa from last night, Alyssa?” – Holden “How do you begin and end a sentence with the same word?”).

It’s all going well until, mid-serenade, it turns out Alyssa is a lesbian. Holden’s world is destroyed and he scampers off at the first opportunity. Reluctant at first, he begins a friendship with Alyssa (complete with lots of naïve questions about gay sex). Banky, feeling discarded by this increasingly close friendship, intimates that Holden is wasting his time (she’s a lesbian, after all—and he’s clearly still in love). Because this is a movie made by a guy from Jersey for (presumably) those of us from Jersey, matters climax at a diner, where, after Alyssa buys him a painting off the wall, Holden confess his love. She’s scandalized and angry, feels put on the spot by his needs and feelings. Alyssa sums it up pretty well by screaming at him mid-breakdown: “I’m gay, Holden!” To accept and return his love would be to betray who she is, the way in which she has made her own life legible to herself. And yet, she caves. They kiss. They have sex. Banky finds them the next morning and, of course, all hell breaks loose.

Banky needs his friend back (Hooper suggests that Banky isn’t ready to accept that he wants Holden as more than a friend, hence his penchant for penis jokes) and digs up some dirt on Alyssa. It turns out she’s quite sexually experienced (with men!). There goes Holden’s fantasy of lesbian conversion. At the same time, Alyssa is spurned by her friends in New York for dating a guy—she’s welcome as a lesbian, but not as a bisexual. I needn’t give the ending away, except to say that Holden can’t handle that she might be more sexually experienced than he is and so offers a threesome between the two of them and Banky as a way of resolving all the problems (Banky gets to see he’s gay; Holden gets to be a little freaky and achieve parity with Alyssa, etc.). Catastrophe ensues.

The menage is, I know now, a terrible idea, and, of course, one that our heroine rejects out of hand. She loves Holden and know what she wants; those were her choices then, this is hers now. His immaturity about her agency (and regrets, if that be the case) is his problem, and, indeed, it is his self-sabotage that he will have to learn to accept.

But that’s precisely why I love Chasing Amy so much. You see, when I first saw this movie at the tender age of 19 or so, I totally thought Holden had a point. My young reactionary male brain came with all sorts of assumptions that were, in their way, really cloaks for my own sense of inadequacy. Now I know this. But back then, my thinking was—um—simpler. I saw Holden’s fears as reasonable, as an outgrowth of a desire for equity within the relationship. Hell, I recall predicting that he would suggest a threesome—not because I could forecast his stupidity, but because his desire to set everything straight in comically cinematic fashion made sense to a mind defined by thoughts of less-than-ness manifesting as machismo.

Chasing Amy is a movie about complex psychological dynamics, including queer identity, yet it’s accessible to the sort of person I was nearly a decade ago when I first saw it. The movie queries the limits of the young male consciousness, but within the very framework in which such a mind operates (like most early Smith outings this movie is full of sex jokes and comic book characters). It takes love seriously as an ecstatic, joyous, destructive, tormenting force that tears apart self-understanding and forces us to rigorously interrogate (and discard) who we are.

Above all, it acts as a kind of introduction to queer and gender theory for the unenlightened layman (and yes, here I am thinking “man,” or perhaps better, “knave”). Hooper X complains that he can’t be public with his sexual orientation because, while the market eats up lesbian comics, there’s no audience for gay male comics (and especially, he underscores, Black gay male comics—at least in his understanding then). And so, he pretends to his machismo. Alyssa is (so we glean) a bisexual who began identifying as a lesbian a as a way of breaking with certain early decisions (and perhaps even traumas). Meeting Holden allows her to question that subtle shift for the first time in years. But her friends don’t understand—they are held together by their lesbian-ness. It is, ultimately, the identity that binds them as a community (and all the more so in, say, the New York of the 1990s). Banky I go back and forth on. But whether he’s gay for Holden or not, his primary identity as best friend leads to his destructive behavior, a decision that ends up blowing up the very thing he loves and thus his entire sense of who he is. Holden comes to realize his paranoid inadequacy too late; he learns the lesson of loss because he could not give ground to his love soon enough. Each of our characters is a confused bundle of drives and masks, united and/or destroyed by the mystical force we call love.

Is that new ground? Not exactly. But it’s new ground for a movie for 90s comic book guys from Jersey. It’s new ground for a film with a ska soundtrack and side characters with lines like, “I love the dick jokes; love ‘em.” And that? That’s amore.