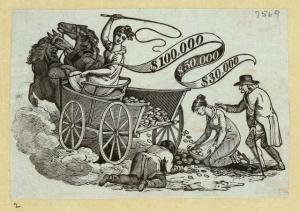

An engraving (c. 187–1880) of Lady Lottery and her patrons. Source: NYPL.

R.W. Fassbinder’s Faustrecht der Freiheit (1975) is usually translated Fox and His Friends. That title is coy and ironic, since our man Fox is a walking “with friends like these…” bit. It does, however, capture the alliteration of the German original and something of Fassbinder’s unhinged and biting sense of humor [most prominently displayed in Satan’s Brew (1976)]. A more literal rendering might be Fistfight for Freedom or Freedom’s Law of the Jungle; these distill things down. Fox comes from nothing; he wins the lottery; his boyfriend slowly saps him of every penny he’s got; his buddies down at the gay bar warn and mourn him. Fox dies; evil wins.

Move over Aeschylus, the barbarians are writing tragedies now…

What Fassbinder does differently, however, is take this melodramatic skeleton and beef it up with the, uh, hearty meat of social critique. There is, of course, a facile way of doing this, shoehorning in issues of the day like an afterschool special (or most of what’s playing now) and then running the plot on autopilot. But the master is too quick for that, and, in Fox, has what, 50 years on, makes our “intersectional cinema” look thinner than a well-sliced cold cut.

In a nod to Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, our main character’s name is Franz Biberkopf (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who lost 40 pounds for the role), though everyone calls him “Fox,” the moniker bedazzled on the back of his denim jacket. We open with a carnival show promising, “Fox, the Talking Head,” a disembodied medium the audience can interrogate as they wish. The barker and carnival owner, Klaus (Karl Scheydt), only gets halfway through his spiel before being arrested on charges of tax fraud. The fully in-tact Fox rushes out; they kiss. While the camera holds on them for a second, the whole thing is treated more as tragedy than exploitation. Fox, we see, is gay—he is also a carnie who just lost his crappy job and his boyfriend.

Faithful to the habitus of poor people everywhere, Fox decides to go play the lottery. He just knows he’s going to win. Leaving behind his roommate and sister, Hedwig (Christiane Maybach), who does nothing but drink since her boyfriend got locked up, Fox, trying to make a quick buck, cruises on foot and is picked up by Max [Karlheinz Böhm, of Peeping Tom (1960) fame]. Max wants to get back to his place, but Fox won’t go anywhere until he’s bought his ticket. Of course, he’s got no money and the clearly rich Max won’t spot him, but that’s no trouble. He’s a carnie, after all. Thinking on his feet, Fox scams a portly florist (and fellow queer dive bar patron) out of enough for one ticket. They drive away.

We don’t see Fox win. But we know he has from the way he’s now hanging out with Max and his effete, bourgeois friends (all gay men). These characters keep commenting on the rough-and-tumble nature of our ex-carnie, never leaving a faux-pas unremarked upon (he wears denim and a wifebeater! Later he won’t know anything about Tchaikovsky—quelle horreur!). One of these cultured acquaintances is Eugen (Peter Chatel), the scion of a wealthy, but down on their luck, family with a printing business. Without even a moment’s thought, Eugen leaves his old boyfriend, Philip (Harry Baer), and shacks up with Fox. It’s all downhill from there.

Summarizing the rest of the film would be cruel. There’s enough wrong with the world without me detailing every awful, depressing thing that Eugen (and really life) does to poor, proletarian (as his “friends” keep calling him) Fox. Thrown out of his apartment for immorality, Eugen convinces Fox to purchase them a new flat and fill it with antique furniture from Max’s shop. Fox discards his trademark denim jacket for a new, stylish wardrobe, purchased entirely from Philip’s store. Fox (as they say) injects liquidity into Eugen’s family business, only to be berated for not knowing which fork is for which course when he goes to dinner at the family’s place. He can’t order at Eugen’s favorite restaurant because he doesn’t know French (in his acerbic way, Fassbinder later undercuts this by showing us that Eugen’s French is itself quite limited). They take a vacation to Morocco where the Arab prostitute they try to bring back to their hotel is turned away by the Arab staff (“we don’t allow Arabs in here”—go figure). The clerk reassures them, however, that the hotel has “boys” they can send up if they wish; they don’t and end up fighting over how Fox can’t communicate with the locals. All this on his dime. When he tries to pick up a couple American GIs, they ask him how much he pays. A bitter irony for Fox, the man who prostituted himself for a lottery ticket, and is now little more than a piggybank for his bourgeois boyfriend.

At the first opportunity, Eugen cuts him loose. He’s fired from the business; the apartment, which he signed over to give Eugen more money-on-hand for the firm, is taken out from under him. His friends at the gay bar say I told you so (but only after he’s hit on by the florist he once scammed). His brand-new sports car is worth nothing to a used car dealer—who wants something so fancy from such a dealership? When he tries to go back to his apartment, he finds Philip living in it with Eugen. Back to square one.

Fox commits suicide with the Valium he’d been prescribed to handle the stress. Eugen and Klaus (his original boyfriend!) find his body, and, first mistaking him for a drunk, comment on how someone needs to clean up the streets. Realizing their error and seeing that he’s dead, they decide not to become involved (“nothing we can do!”). The credits roll as Fox’s body, including his beloved jacket, is picked clean by a couple young kids.

In the end, the low-class scammer gets conned by his social betters. It’s Nightmare Alley (1947) meets Douglas Sirk, an object lesson in the ways love can be exploited, in the Faustrecht of life on the margins. At the same time, Fassbinder edges in all sorts of other critique. Class is at the center; there’s no question about that. But in Morocco we see how casual sex tourism takes advantage of postcolonial peoples (while excluding them from even the brief respite of an air-conditioned hotel room). Then there’s the horror of these “boys” in Morocco. In Hedwig we see how incarceration destroys families. Eugen loses his apartment for being gay. Nearly every woman in the film, from Fox’s sister to Max’s wife is trapped at home, drinking (and probably taking the same Valium doled out to Fox himself).

Despite this relentlessness, the film is never moralizing or objectifying. It’s not about being gay or being a man or even being poor. Fox and His Friends is about the cold logic of chicanery that rules our world, where the craftiest and those who start with the most have the best shot, a world where even winning the lottery can’t save you.