Source: Wikimedia

If you’re looking for a great documentary, look no further than Vice’s YouTube showcase of Valerie Blankenbyl’s The Bubble (2021). Put aside the true crime. Think about cults some other time. It’s free, folks. It comes complete with an interview with the director. You’ve got no excuse.

If you read the comments on the video, you’ll see that many are praising its balanced take on a situation so emblematic of the time in which we live that it feels foolish to even point it out. The Villages is an ever-expanding retirement community 50 miles out from Orlando, Florida, where Northern snow birds can make the migration complete, exist within, well, a bubble. They’ve got cul-de-sac on cul-de-sac, modern ranch homes, and well-manicured lawns winding around “town squares,” replete with all manner of shops nightclubs, pools, restaurants, and every other sort of amenity. They have their own newspaper, radio station (constantly blaring over speakers throughout the gigantic development), and even (illegally) have the public roads through the area gated. Time and again we meet residents who say it’s their time—they gave everything to their families and children and now it’s their chance to relax and enjoy life. These Boomers, in their own words, want nothing more than the freedom to exercise or not exercise, to drink all day, attend yoga ball drumming classes, golf, and sing karaoke by moonlight.

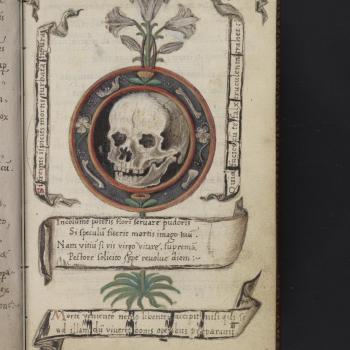

We also meet the residents of the surrounding rural area, at least those who are left. Some, like the owner of a combined gun and jewelry shop, like the Villages—it’s been great for her business (the old folks like to go to the range). Others, like an ex-fire fighter and tree nursery worker, resent the destruction of local wildlife, the sapping of the water table, and the destruction of the way of life so many have known for so long. One local woman exits her church to show us the gravestones of several relatives, doomed, should the Villages succeed, to meet the bulldozer, unless their skeletons are rescued and reinterred.

It is, in that sense, a balanced film. The director-interviewer is never hostile and hears everyone out. She lets the subjects speak for themselves, and never shies away from showing the old folks having fun, truly getting what it is they claim to want. That, compared to, say, a Michael Moore film, hints at a consciously “fair” doc, so just and weighted, in fact, that some commentators who live in the Villages call it well done!

But such a view ignores the astonishing cinematography and editing The Bubble has to offer. It takes the thing to be nothing more than its dialogue, mistakes the director’s (let’s call it) European manners for a lack of commitment to criticism. Take the opening scene. We’re in an evangelical church, swathed almost entirely in shadows, with some highlights on what’s more or less the apse (not that evangelical churches really have apses, but whatever, this reviewer has the background and vocabulary he does). The preacher winds back and forth, voice modulating up and down, captivating his audience of retirees. We cut to their faces over and over, fixed with rapt attention. He jokes about their finally getting away from the snow, the stress, the fast-paced way of life up North, the old house and troublesome family, how now they can drink margaritas all day. But, he adds, “you can only down so many drinks. Maybe your relationship with God has suffered; now you have a chance to fix that!” Inspiring! But if we look closely (the camera is fixed behind him as he wanders up and down the aisle) we see a board, high up, behind the audience. This board has the pastor’s notes, down to the “AND THAT’S GREAT!!” in reference to their taking on the slower, Floridian life. It suggests that the entire experience is manufactured, that this is really a bubble, a constructed experience meant to hide the world, infinitely duplicable until the world itself blazes out or old people decide they’d like to retire in some other way. Of course, the denizens of the Villages don’t care—that’s what they want. But the camera is insistent: you cannot escape the artifice of this place. What seems genuine, what may be truly emotionally affecting, is ultimately an act.

This perspective is clearest in the many, many shots of the houses in the privately-owned and -operated development. The cinematographer makes sure the green pops against the grey of the streets and homes, there like little splotches. The shots are almost always symmetrical, calling to mind the 50s ads for Levittowns. At one point, we get an impressively stark shot (also symmetrical, of course) of where a plot of grass meets a driveway. It looks like a Rothko painting, these bare rectangles of color clashing, evenly matched and always manicured. Blankenbyl constructs the suburbia of The Stepford Wives (1972) or Pleasantville (1998) without ever having to say it. The place feels like a fantasy, a reconstruction of the idealized childhood neighborhoods of the residents, updated with modern amenities and more contemporary activities. It equates these Boomers’ desires for fun and relaxation with a nostalgia, a desire to retreat into childhood.

Startling juxtapositions underline the point further. We see shots of butterflies and other bugs flying and landing on various leaves and flowers, all on or around the property of one of the Villages’ opponents. What do we cut to but a resident of the development asking why they even have window screens. There are no bugs in the Villages. “What’s a mosquito?” she asks sarcastically.

The Villages gets away with what it does because, as it turns out, the developers are major GOP donors and the residents (who vote as a bloc) are staunch Republicans (we see a Trump golf cart parade protested by one, lone Biden voter). They alone can elect representatives, independent of the rest of the county, at least in one local’s estimation. They have clout and the others don’t. The water table will collapse. Sink holes will keep on popping up (or sinking down). The 150,000+ population of the Villages will grow and grow. No one seems able to stop it. And the movie makes no attempt to assure us that anyone will, though we meet noble opponents of this future during its 92-minute runtime.

Above all, that’s the key to The Bubble—a willingness to rediscover the anti-developer movie. We got these all the time in the 90s. My own memories of childhood are replete with the image, not least because of Hey Arnold! The Movie (2002), in which the titular character and a multiethnic coalition of neighbors find a way to stop a Robert Moses stand-in. These days, developers are more popular “on the Left,” with anyone suspicious of them labelled a “NIMBY.” But, in my eyes, there’s a difference between simply fearing change or being xenophobic and watching your community get torn apart by speculation. Anyone living in a post-industrial town or city knows the phenomenon of luxury apartment buildings, cookie cutter boxes assembled with Legos (seriously, see how they’re made), with maybe (if you’re lucky) a few (still pricy) “low income” apartments on offer.

Of course, these edifices are not the Villages, and it’s not exactly the same problem. But just to see a documentary in which the wisdom of development is called into question, and to do so with style—that means the world to me (even if the world is getting destroyed in the process).