Source: Flickr User Tony Hoffarth

License: Creative Commons

It’s not giving much away to say that 500 Days of Summer (2009) is about a break-up. The movie takes a nonlinear tack in exploring the year and a half Tom Hansen (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) needs to date and then get over Summer Finn (Zooey Deschanel). The two meet at the greeting card company where they both work, enjoy a tempestuous romance, and then split. The constant cutting between the present and past, ostensibly a way to show us the sunny development of affection from the perspective of a doomed pairing, gets old pretty quickly—or at least did for me. If Annie Hall (1977) is the story of two people growing apart and The War of the Roses (1989) traces the rise and fall of a marriage, this Marc Webb-directed effort is a science-class dissection. From the first scene, it loudly declares that Tom is unhappy, a rejected lover whose story will be told largely to investigate how (and if) one can get over investing in romantic folly. I’ll save you the watch: one can, though only by accepting cruel truths about the human condition. Love is provisional; there is no wyrd governing the fickle hearts of men. One could imagine Tom as a distant, less-eloquent cousin of the speaker in Thomas Hardy’s “Hap”:

If but some vengeful god would call to me

From up the sky, and laugh: “Thou suffering thing,

Know that thy sorrow is my ecstasy,

That thy love’s loss is my hate’s profiting!”Then would I bear it, clench myself, and die,

Steeled by the sense of ire unmerited;

Half-eased in that a Powerfuller than I

Had willed and meted me the tears I shed.But not so. How arrives it joy lies slain,

And why unblooms the best hope ever sown?

—Crass Casualty obstructs the sun and rain,

And dicing Time for gladness casts a moan…

These purblind Doomsters had as readily strown

Blisses about my pilgrimage as pain.

This reading, however, upsets the standard line on 500 Days of Summer. A more enlightened interpretation goes something like this: a first viewing should lead one to sympathize primarily with Tom, from whose perspective we experience the action and whose emotions we share throughout the relationship. Later sessions should inculcate some sympathy for Summer, who constantly reiterates that she doesn’t want anything serious. Finally, in a sort of pseudo-Hegelian synthesis, we should see that both parties are flawed. Tom naively believes the two are fated to be together; he projects onto Summer the woman he wants to marry, rather than accepting her for who she is. Summer, by contrast, does not know herself and, while largely honest about her desires, often misleads Tom. She is unsure of who she is and, as a result, flirts with disaster (and, of course, a guy named Tom).

Talk about projection! This reading attracts people, I think, because it displays a certain degree of emotional maturity. If we can see how both are wrong, we implicitly pat our own backs for our own development. The problem is that the film itself isn’t quite so complicated.

From the very beginning, we see Summer as simplistically herself, immature even. In the narration that opens the movie, her distrust of love and relationships is linked to her parents’ divorce (an all too real, but also rather one-to-one explanation). Throughout the 96-minute runtime, she tells Tom she doesn’t want anything serious, only to invite further exclusive romantic connection. Take, for example, an incident in which Tom punches a guy at a bar. She (and most viewers it seems) takes this as macho posturing, an attempt to defend her from unwanted attention (never mind that the dude keeps insinuating that he can’t believe Summer is with a loser like Tom). Once home, she explodes at him, declaring that she can defend herself. Tom draws a line in the sand. He’s tired of her waffling—either they can be an item or he’d like to end things. Does she end things? Take a guess.

Once they do break up, Summer sees Tom on a train and asks why he hasn’t answered her emails (again, take a guess). Later, she has him to a party, only for her to get engaged at the event. She then invites him to the wedding, meeting up with her ex before to (in a trope so old it could marry a Civil War veteran) hash out their failed relationship before she ties the knot. When he asks about the whole complicated relationship thing, she just hits back with “because I felt like it,” a response so entirely devoid of introspection it could disappoint a cardboard cutout.

The problem isn’t Summer per se (she’s a movie character after all); the problem is the film’s presentation of Summer. Tom is admittedly naïve (a fact addressed in on-the-nose fashion in the ending), but Summer comes across as equally so (or worse, manipulative). The only information we get about her reasons for leading Tom on, even after he presents her with his need to be exclusive, is a canard about her childhood (and not even from her own mouth!). After their fling fails, we get simplistic justifications and the emotional equivalent of a frowny-face emoji, suggestive of little more than fickleness based on intuition.

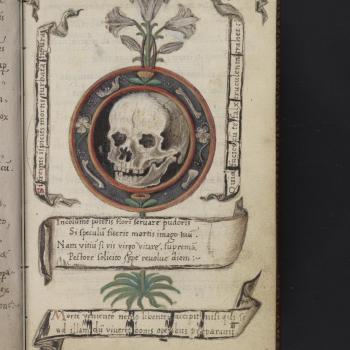

Had the movie spent less time cutting between different moments in their lives and settled on a linear narrative, it might have had time for Summer the person, rather than Summer the not manic, not pixie dream girl. We might have felt her develop from an emotionally-closed child of divorce to a young woman open to love, might have seen her pulled in two directions at once, intrigued by Tom but unwilling to surrender her guarded soul. Alas, we get none of that, are left with Hardy’s “Hap” in the person of a greeting-card writer turned architect (something like if George Costanza had actually become Art Vandelay). But we don’t quite see even that really. 500 Days of Summer offers up something closer to the medieval knight afflicted by love sickness, an Yvain, driven to bestial insanity by unconsummated or unrequited desire. When I put it that way, it doesn’t sound half bad (not that the movie is terrible in any case). Maybe, though, that’s just the psychoanalysis talking (or, indeed, the medieval romance):

It is fitting to hate and blame and despise myself, even as in fact I do. Whoever loses his bliss and contentment through fault or error of his own ought to hate himself mortally. He ought to hate and kill himself. And now, when no one is looking on, why do I thus spare myself? Why do I not take my life? Have I not seen this lion a prey to such grief on my behalf that he was on the point just now of thrusting my sword through his breast? And ought I to fear death who have changed happiness into grief? Joy is now a stranger to me. Joy? What joy is that? I shall say no more of that, for no one could speak of such a thing; and I have asked a foolish question. That was the greatest joy of all which was assured as my possession, but it endured for but a little while. Whoever loses such joy through his own misdeed is undeserving of happiness (Yvain, the Knight of the Lion)