Source: Stockvault

Public Domain

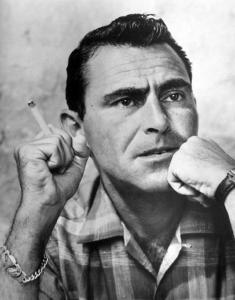

I caught some flak for trashing Barbarian (2022). I’m not surprised. I hated the pilot of The Last of Us (2023) too. I’m not exactly a Pez dispenser; I seem to have more vinegar these days than honey. Just the day before I wrote that review, I taught a class on reboots, revivals, and adaptations. Our case study was The Twilight Zone (original run, 1959-1964), which has been revived for TV three times (never mind the short story collection, feature film, TV movie, radio series, and countless childhood nightmares). My students looked nonplussed. They usually do, not just because I’m a shmuck though (true as that may be). They just didn’t seem all that enthralled by the show idea. Here I am entranced by “Five Characters in Search of an Exit” (1961); here they are texting and snickering at a languid hobo.

I got to thinking: what beyond nostalgia made those classic episodes so enchanting? I can’t imagine telling a Zoomer, “no, no. It’s a pun; it’s a cookbook!” or “get this: the guy’s nuts AND he sees a gremlin on the wing of the plane. Or does he?” would get me very far. They are largely simple tales with bare plots and weird twists. Some are moral stories, uncomplicated reflections of creator Rod Serling’s battered humanism. Students even suggested to me that the show worked because 50s viewers expected less. As Norm Macdonald said about Brokeback Mountain (2005), “I wanted to see a guy in a white hat and a guy in a black hat shooting each other in front of the saloon, you know?” That’s appealing in its way; it has the ring of truth. But then you watch the pilot episode of the acclaimed series The Last of Us and realize we love the same slop we always have. We’re no more complicated than 50s TV viewers; we just like our pounage with a bit more acorn and a bit less hawthorn.

Then my friend J.G. Michael of Parallax Views descended like Raphael himself, a messenger from my old friend, the Creator, YHWH, Elohim—the big guy. He recommended (not knowing of my plight) Lucky McKee’s Old Man (2022). I am a praying man. But that doesn’t mean I get round-peg-round-hole answers all that often. That just means I like to sit in silence and wrestle with words in my head. Talk about an answer!

Old Man is carried by two actors almost entirely: Stephen Lang (who plays the Old Man) and Marc Senter (who plays Joe). The whole movie takes place in the Old Man’s cabin, where we see him wake up, angry that his dog Rascal has peed inside and run off. He drinks hooch; he curses his pet, threatens to cook and eat him. Then there’s a knock at the door. The rest is My Dinner with Andre (1981) if it took place in the Smokies. These two phenomenal actors carry us through the ebb and flow of fear. Is the Old Man a maniac? Is Joe really just a hiker? Senter plays Joe with just enough soft oddness; he’s too calm, too straightforward, too demure to find himself 100 miles out in the woods. The Old Man loves toying with his guest, but he’s also inviting, and (understandably) suspicious: how does someone end up that far off the beaten path anyway?

The one bit of praise I offered for Barbarian concerned the tight suspense that emerges in the first 15 or so minutes. There we had two Airbnb guests forced to share a double-booked house in a bad neighborhood. One male and one female, they’re feeling each other out, their potentials for violence, just how much trust is worth placing in a stranger.

That one goes off the rails; it becomes horribly (ha) unsubtle. Old Man does not. There is a twist to come. It’s not one that exactly reinvents the wheel. But it’s not beaten into your skull at every point either. Odd cinematographic decisions make more sense once you know; you’re left with the thrill of a pulpy turn, sure. Though that’s just it: the twist doesn’t really matter. It works as 70+ minutes of suspenseful dialogue and blocking, two men dancing with words as they uncomfortably shift their bodies, pick up guns and put them down.

The same goes for the movie’s themes. As with any Lucky McKee film, questions of misogyny, human violence, and transgression are present. But they show up as just that: themes. They don’t infuse every line of dialogue, nor are they exactly the subject of conversation. They emerge through the characters’ decisions, motions, and emotions. They aren’t cudgels to be wielded in judgment over choices, but rather are questions immanent to the human character.

That’s what makes the Twilight Zone work too. Seriously, check out “Five Characters in Search of an Exit.” The shots themselves outclass most prestige TV today. Most of the episode is just a bunch of weirdos talking to each other, musing about life. There’s a twist (though no gore, since it’s early-60s TV). These offer the thrill of suspense (who are these characters? Who is the Old Man?) and the human acknowledgement of complicated, horrifying realities, those that dog us all, no matter who we are or where we live. They balance escape with universal (I know; I know—I use the term ill-advisedly) conditions. What could be more horrifying?