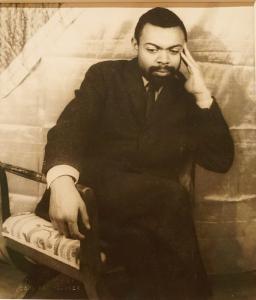

Source: Flickr User Regan Vercruysse

License: Creative Commons

In 1959, bit TV actor and anti-Lee Strasberg workshop founder John Cassavetes filmed a 16mm, largely improvised movie about race relations in contemporary New York. That work, Shadows (1959) seems to attract admirers mostly because it ends with a (then-surprising) note about its improvisation—a triumph of independent cinema, the ill-attended foundation for Marty Scorsese and New Hollywood. It’s, the consensus is, an artefact for contextualization, a bauble to be praised by weirdo enthusiasts and snooty cinephiles, a 20th-century Ormulum.

It is so much greater than that, though with a caveat or two. Cassavetes’ film manages to be more advanced on racial politics than many of today’s “most radical” films while also employing practices now widely condemned, even in more politically reactionary circles. Like Nella Larsen’s Passing (1929), it presents colorism within the Black community. At the same time, two major Black characters are played by white actors. Its impressionistic style (including a jazz soundtrack from Charles Mingus and Shafi Hadi) crafts more than a slice of life, an inspiring proto-The Graduate (1967), or condemnable bit of well-meaning racist nonsense. Shadows offers a lesson in radical politics and the biases that so often hold them back. More than that, however, it entertains, presents a gripping tale of people living their lives as human beings do.

At the heart of the film are three Black siblings: two struggling jazz musician brothers, Hugh (Hugh Hurd) and Ben (Ben Carruthers), and their strong-willed but naïve sister, Leila (Leila Goldoni). Ben is light-skinned and wears sunglasses with leather jackets at night. While he claims to be a trumpeter, we mostly see him get drunk with his white friends and try to pick up girls. Leila too passes and floats in and out of three relationships over the course of the movie (two with white men, one with a Black man). Only Hugh is obviously African American. He’s an old-fashioned singer who can’t work, half on account of ubiquitous racism and half because he prefers an older kind of jazz no longer in fashion with the white audiences who populate clubs. Only he must deal with the everyday problem of being Black.

The emotional heart of the film, however, concerns Leila, who begins seeing (and then loses her virginity to) a white Beat (the whole family is half awash in Beats) named Tony (Anthony Ray). He reacts with surprise and horror when he learns she’s Black. This is, it seems, her first experience of racism as such. Earlier in the movie, Leila walks home alone from Port Authority at night despite her brother’s warnings. A man tries to grab her. She seems surprised then too, as if the lights of Times Square promised safety rather than depravity.

By the end, Leila has begun asserting herself. She makes her new boyfriend, Davey (David Jones), wait for hours while she gets ready, testing his patience to make sure he won’t run like Tony, even though he too is Black. She toys with him as they dance, loudly making embarrassing comments. He is confused and gentle despite it all. Her responses are, in their way, immature. But they also betoken her growth into cautiousness. She has become defensive and brash but also wise and assertive.

For his part, Hugh shoulders the constant disappointment and decides to press on in hope with his manager Rupert (Rupert Crosse). Ben fights and drinks, seems to experiment with horse (I can’t help myself). As the runtime winds down, however, he agrees to convey an apology from Tony to his sister. He may be too cool for most things; at least now he’s not too cool for his family.

I belabor the plot details because too often people think this movie has a rote narrative, too improvised to achieve anything (tell that to Scorsese and his happy troupe). At bottom, Shadows, even at the level of its story, tracks common racial and non-racial experiences and the ways people build their personalities in reaction to them. Leila escapes assault, loses her virginity, and comes to know her own Blackness through racism. She becomes colder, harsher, but not unwarrantedly. Ben confronts his own dissipation, including how a supposedly non-racist friend, a fellow member of the Beat Generation, could reject his sister because she descends from slaves. Hugh plays mother hen, performs the role so well he no longer knows what the white audiences he needs want to hear. His faith, by the end, is in his Black manager and friend, Rupert. Solidarity keeps him pressing on.

Cassavetes’ signature impressionistic style lends the movie an even greater air of verity. We begin with Ben walking down a busy New York street. Only slowly do we meet his siblings and discover the network of people who connect them. A few bars here and there punctuate cuts between scenes or prominent moments. We float in and out of parties (one largely white, one largely Black), trapped in close-ups on faces, drummed up by rapid cuts, into experiences of ecstasy, suffocation, and horror. Regardless of race, snooty people make the kinds of comments one might hear at a lit party (“A literary party,” one character asks, “what’s that?”). Class politics are always there in the background, never dwelled upon, but soaked into the marrow of Cassavetes’ world. These Beats and hooligans are never quite comfortable talking sculpture or poetry. This discomfort, however, cannot provide cohesion when society teaches them to separate themselves based on race.

The catch, of course, is that neither Ben Carruthers nor Leila Goldoni is Black. I presume they were chosen for the roles because Cassavetes’ studio had no extremely light-skinned African-American members (all the actors came from his classes). There’s no severe, minstrel show-esque blackface in the movie, though Carruthers seems to be wearing the 50s equivalent of bronzer. I can’t say that’s a good thing, though, given how recently people have been caught going full Amos and Andy, it’s not all that surprising. Still, the movie’s politics and style make these choices ignorable, if not forgivable, just as the complexity of its story and themes make it more than the fundament of New Hollywood. Shadows is a work of political and artistic excellence on its own merits—and it keeps you entertained too.