Source: Picryl

Public Domain

George A. Romero’s Martin (1977) does for the vampire film what Night of the Living Dead (1968) did for the zombie flick. Here, there is demystification. Just as Romero’s more famous films avoid Haitian witch doctors and talismans with mystical powers, so does Martin reject any of those old, bloodsucking stereotypes. Martin (John Amplas) himself spends hours calling into a radio show, laughing at the idea that he has a seductive hypnotic stare, that garlic can stop him in his tracks, or that the sun burns away his pallid skin. He doesn’t even have fangs! Needles filled with sedatives and razor blades are more his thing. Sexually, he’s a loser, too shy to go after any lady who’s awake. Working class (and certainly no aristocrat), Martin is a vampire unlike any we’ve ever seen: a bashful delivery boy with a charisma made for the fans of Elliott Smith or American Football, not the dedicatees of Vampyros Lesbos (1971).

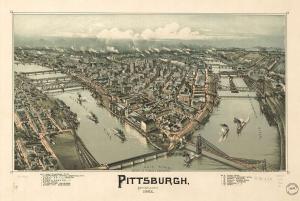

Martin, you see, has come to a town outside Pittsburgh to live with an elderly cousin, Cuda (Lincoln Maazel) and his granddaughter Christina (Christine Forrest). Cuda is convinced their family is cursed, that Martin, though he looks like a young man, is an 80-something year old vampire who must repent before he is killed. Christine thinks this is all nonsense. Martin drinks blood, sure. He conceives of himself as a vampire, even seems to believe he’s as old as Cuda says. But are these delusions? Social pressures created by this notion of a familial curse? Or is he a flesh and blood vampire, simply of a kind yet unknown to the Western moviegoer?

Matters are made more complicated by Martin’s bizarre visions. During moments of bloodlust, he sees black-and-white set pieces straight out of a Universal monster movie—torch-carrying mobs, seduced damsels, and cold, stone-walled Old-World castles. Romero builds these ambiguities into the very fabric of the film, cutting back and forth between Martin’s mundane life as a delivery boy for his relative, his Romantic visions (or are they memories?), and his half-witted plans to drug and drain the people of Braddock, PA.

But the question of whether Martin’s vampirism is “real” or “fake” is less interesting (to me anyway) than the film’s transposition of 19th-century European myths, creatures, and fables into 20th-century American society. Martin is what remains when you strip the Gothic shadows, the unsettling, otherly ambience from vampire stories. He lives in a Rust Belt suburb, one we are often reminded everyone under the age of 40 is leaving. His castle is a small bedroom in a modest home. His victims are a woman on a train, an adulterous couple, the homeless. At one point, he puts on fake fangs and a cape to mock Cuda’s beliefs. Where does he stage his mockery? A dour, cement-laden alleyway or parking lot, the sort of place that’s full of dumpsters, rats, and Big Mac wrappers.

Religion, too, shifts and squirms under Romero’s retracing of the vampire legend. Novels like Dracula (1897) trade in classic British fears about sexually rapacious Catholics, holed up in their grand, medieval castles, attractive in their outdatedness, though always to be feared. Such traditions grew out of Gothic novels like Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1794). Its Italian setting, spooky quasi-medieval castle, and its frame narrative (said to have been discovered among a recusant family’s books) built the foundation for much British vampire literature. In Martin, however, Cuda is the religious zealot, trying to save his relative with exorcisms and constant recognition of his inhumanity. The Catholics here are the hunters, the purists, the ones who make up stories about bloodsucking seducers who must be deterred with garlic, who can’t see themselves in mirrors.

In this sense, Romero’s film brings the vampire story full circle: now the world has moved on, no longer afraid of such creatures of the night. Just as the industrial cities and suburbs of Western PA have been disenchanted, so has the vampire myth. Only elderly Catholics with drunk priests even begin to care. Now the Catholics aren’t to be feared; they are those who fear. There’s something of Lovecraft in this WASPy dismissal of the mystical. But Romero himself is no WASP, and the movie strikes me as a story about the loss of belief (in anything, even in the charms of the vampire) more than it does a tale of Catholic superstition. Even they, as we see when meeting the drunk priest (played by Romer himself!), are a little too worldly now for such trifles.

That’s really what makes Martin work so well. Romero entertains even as he questions. Tightly paced and brimming with tension (especially in the sequence with the cheating wife), the movie never gives us a moment to engage with this disenchantment. It is our world, after all. It’s what we know. There’s not much to contemplate: we’re stuck with the rust and decay just as Martin is.