Source: Wikimedia user Mike Hall

License

Ten years ago, two friends and I holed up in a cabin in Woolwine, VA, a town whose claims-to-fame are three covered bridges (one of which was destroyed by a flood in 2015). We hailed from suburban New Jersey. At least two of us called red sauce “gravy.”

Poorly planned, as a trip composed of late-teen and 20-year-olds would be, we arrived during a frigid, barren winter. Aside from getting found out the first time we stopped for a hot dog (turns out flannel shirts and blue jeans do not country boys make) and getting caught in a speed trap down road from a Burger King in West Virginia, my memories of the trip are pleasant, touched by a decade-long remove from youthful naivete. I slept on a couch in three pairs of socks because there weren’t enough space heaters, and we could hardly keep the wood stove going through the long, icy nights. We shared literary dreck with each other and walked up and down dead-tree hills, gawked at cows on ridgelines, and ordered “kaw-fee” in a county named for Patrick Henry. I could not stop remembering my cold feet and the cabin-accurate décor while watching Withnail and I (1987).

This might seem an odd association. Bruce Robinson’s classic comedy is cringe inducing and deeply, existentially sad. Much of the laughter comes from Withnail’s (Richard E. Grant) posh, alcoholic rage at a society that won’t give him TV parts. His fury can’t even be met halfway. His agent hasn’t even landed him an audition for TV! The audacity! Withnail “& I” (Paul McGann), take off from their crumbling, rat infested, dishwater-soaked, booze-dripping 60s London flat for the open pastures and good, clean air of Withnail’s uncle’s country house. They turn out to be about as adept at navigating country living as three Jersey boys stopping for hot dogs in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Uncle Monty (Richard Griffiths) himself shows up, bringing aristocratic comfort and a comedy of errors so painful it evokes the geometric grandeur of Shakespeare and the slapstick campiness of Benny Hill. It doesn’t make matters any better that “I” is getting auditions. He drinks and carouses like Withnail but with none of the socially adroit savagery and zeal for pain. He is not stuck.

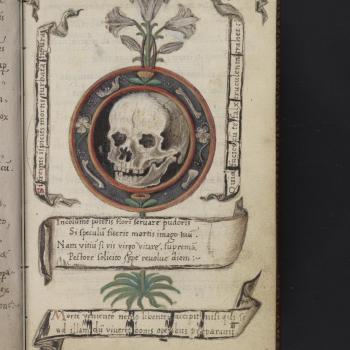

There remains, however, a certain joy in watching the movie. Any would-be artist coming out of their teenage years has to recognize the characters’ jolly experimentation, pomposity, and (above all) fear. The world is your oyster. Trouble is the oyster can bite down hard and fast. Things emerge and slip away quickly. The whole deal is amorphous, exciting in its indeterminacy. With every perceived slight or failure, you become more and more of a Kierkegaard, damning the world in its phoniness and injustice. Then you grow up and settle into a job in insurance, or, you know, cut your hair for a role in a thoroughly bourgeois Scandinavian stage play.

Withnail is 29. I am 30. I am not an upper-crust drunk. Withnail’s nose is rosy, his skin pallid. We’re both romantic cynics (how else explain the finale’s recitation of Shakespeare?). I’ve made my accommodations with life. I’m a bit embarrassed of the spiritual turtleneck I once was. But embarrassment doesn’t mean repudiation; it brings a kind of intimate fuzziness, an appreciation for youthful vivacity.

The lesson, if there is one, is not to be consumed by that disappointment, to remember the foibles of the cabin well, to smile at lapses in judgment that didn’t kill you. Withnail never lets go, never stops taking himself so seriously. That’s how you end up in the cabin at 30 not 20. That’s how ill-informed Uncle Monty comes creeping in the night.