Source: Flickr user Cornerhouse

License

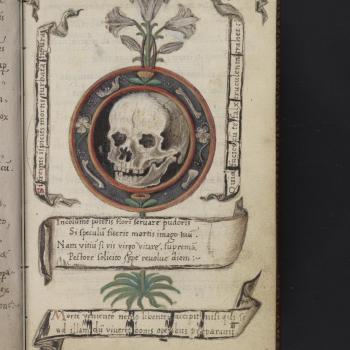

The idea goes that to say someone lives in “interesting times” is an insult or a term of pity. Europe in 1348-1349 would have been rather interesting—lots of puss, merriment, prayer, and death. The last days of the Aztec and Maya must have been something to behold, though not so much for those who lived through them. Imagine standing in the trenches along the Western Front. Boring in the day to day, sure, but the soldiers did live in rather “interesting times.”

At the risk of over-emphasizing my own moment, these times are beginning to seem “interesting.” A general sense of powerlessness does not help make them any less so. It only adds to the effect. Movies, I find, can help. They afford an outlet, a reminder that times have been interesting over and over again throughout history, even if in a special way each go-around. Mike Leigh’s Naked (1994) played just such a role for me this week.

Naked concerns Johnny (David Thewlis), a talkative, apocalypse-obsessed vagabond from Manchester. After getting rough during a sex with a woman who already has a boyfriend, she screams and shoos him off. Afraid for his life, Johnny flees to London, to the apartment of an ex-girlfriend. He wears ratty clothes, has a scraggly beard, and talks with the insightfulness—if not the incoherence—of a dorm-room weed dealer. He wanders the streets, meets various lower-class denizens of London, and continues to seek violent (though usually consensual up to a point) sex. His life manifests the anxieties and base realities of subsistence in post-Thatcher Britain.

If that sounds depressing, it’s because it is. Naked is a dread-inducing viewing experience; it made me squirm from almost beginning to end, though Leigh throws in moments of tenderness, as when Johnny meets a lonely security guard who lets him in from the cold. They offer some respite, rest of the sort we need to go on. Not everyone is evil in this world. Some are just beaten down, like, for instance, Sandra (Claire Skinner), a nurse who has “made something” of herself, even if it’s not clear what making it even means anymore.

I suppose that’s what so moved me about Leigh’s film. In interesting times, there’s no difficulty in believing in evil, in people’s abilities to hurt each other. What’s harder is accounting for it, making space, so to speak, for understanding. Johnny resists any simple psychologization; there’s no straightforward loss of his mother to explain his deranged behavior. But something has obviously gone wrong here, and we know that because we catch glimpses of kindness in him. Unlike the rich landlord Sebastian (Gregg Cruttwell), he does not torture others for his sadistic pleasure. Johnny sabotages himself, gets wrapped in theoretical questions, lost in riddles, until he’s annoyed or hurt everyone around him. His ex and her roommate still love him in their way. The spirit of life remains strong in him, even if we’re never entirely sure why.

There’s a hopefulness in that, which seems to be Leigh’s specialty. He finds ways to locate glimmers of light in epochs of pitch darkness. Naked is no exception. It helped me to feel less alone, if not less hopeful than at least more wiling to try to understand, to want to want a better world despite the way of things. It made people and my hope for them, rather than the times, interesting.