(This post is part of a series. Part one can be found here).

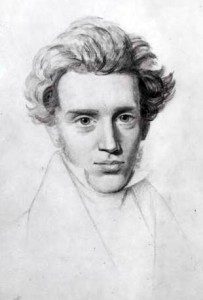

If Nietzsche cleared the ground for my Christianity, sweeping away bland liberalism and all other manner of modern panaceas, Søren Kierkegaard convinced me that only Christianity could fill the void (as if it could be filled in this life).

Plainly put, Kierkegaard’s writing speaks to the modern (and post-modern) experience of fragmented loneliness. As the great opponent of Hegelian systematizing, his writings display a typically Scandinavian taste for irony, harshness, and anxiousness (one need only watch the films of Ingmar Bergman, Lars von Trier, and Joachim Trier to see my point). Two passages from his journals spoke to my teenage soul, long before I could take his theological teachings seriously: “I have just now come from a party where I was its life and soul; witticisms streamed from my lips, everyone laughed and admired me, but I went away — yes, the dash should be as long as the radius of the earth’s orbit ——————————— and wanted to shoot myself.” Here, Kierkegaard channels Augustine. No amount of peer-popularity or earthly happiness suffices to dull our restlessness, our Unheimleichkeit. The second (from about a decade later) develops this idea: “Since my earliest childhood a barb of sorrow has lodged in my heart. As long as it stays I am ironic — if it is pulled out I shall die. A touch dramatic, but true to my own experience (then and now) of using humor to cover over an innate melancholia. Even if nothing can cure the longing, participation in certain modes of living can dull it.

Here I had a Christian who refused to make Christianity something mundane (in both the contemporary and the etymological sense). This man refused to see comfortable bourgeois living as the end-all-be-all of faithful existence. One must make a commitment to serve God and accept all wavering as an inevitability; one cannot serve God and Mammon (that is, the world) because one asks us to sanctify the other, to love it because of Him. Any loving of the world on its own would simply leave us inhabiting an unfair world with limited external consolations. And, as I spoke about last time—the world did not seem to offer much.

Hence, this by-now-famous quote from Kierkegaard’s journals: “What I really need is to get clear about what I must do, not what I must know, except insofar as knowledge must precede every act. What matters is to find a purpose, to see what it really is that God wills that I shall do; the crucial thing is to find a truth which is truth for me, to find the idea for which I am willing to live and die.”

“Truth is subjectivity,” as he would later write, meaning that the truth only matters insofar as we live and die for it; a cold, objective truth lying outside appropriation by people cannot help to draw us away from loneliness and into the bosom of the Lord; such “truth” cannot sanctify the world. It is a denial of that most holy prayer: “Thy kingdom come; Thy will be done, on earth as it is in Heaven.” Hence, writing in the guise of Anti-Climacus, Kierkegaard declares: “Every human being is spirit and truth is the self-activity of appropriation.” More on this note: “The inwardness of truth is not the chummy inwardness with which two bosom friends walk arm in arm with each other but is the separation in which each person for himself is existing in what is true.”

I don’t mean to belabor the point, but I really can’t stress it enough: because the world seemed intrinsically unfair to me, I desired a God whose love called us out of living like other people, who called us to find individuality in self-negation, to find truth in lived action, to live not such that we transcend suffering or make sense of it, but such that we recognize it, look it in the eyes, and then give praise. To paraphrase Kierkegaard, Christianity is the crucifixion of the intellect. To this day, that idea sticks out in my head, pushing back against complete fideism, but recognizing that our reason is meager and befuddled. Hence why the Eastern Church calls the “Sacraments,” “Mysteries”; hence why we serve expecting no reward (even thinking we will be damned!) for our service; hence why we spin as the lilies in the field.

In short, I desired a religion that made radical demands of me, pushed me to love in the face of unimaginable bleakness. Christianity was just this. There were to be no excuses for one’s own sins, but one should forgive all others, never condemning any but oneself. One might be justified in human terms, but there could be no escape from God’s eternal love, a love so overwhelming that it invites us to consciousness of every wrong we commit, no matter how acceptable to the world.

Everyday matters like violence, lying, and lustfulness did not disappear, but their ultimate power did. We might wage just wars, but even those should be committed in a spirit of contrition for taking life (hence the Eastern practice of disallowing soldiers, even in just wars, Communion, for a time. St. Basil said it should be three years!). We might lie because we are weak, but such actions are not justified; they should lead us to prayer. Even Abba Moses of Egypt could not escape his lustful thoughts, yet, with counsel and prayer, he abided in his holy life. Christianity told me that I had to be responsible for my actions, that I had to love in the face of hate and forgive in the face of accusation. No earthly evil could be justified, though all could be forgiven.

This was a religion that could illuminate a seemingly senseless world, a religion for the confused, the lost, and the melancholic. This was a religion for the sinner. Again, I commend you to Qoheleth:

Remember your Creator in the days of your youth,

before the evil days come

And the years approach of which you will say,

“I have no pleasure in them”…When one is afraid of heights,

and perils in the street;

When the almond tree blooms,

and the locust grows sluggish

and the caper berry is without effect,

Because mortals go to their lasting home,

and mourners go about the streets;Before the silver cord is snapped

and the golden bowl is broken,

And the pitcher is shattered at the spring,

and the pulley is broken at the well,And the dust returns to the earth as it once was,

and the life breath returns to God who gave it.

Vanity of vanities, says Qoheleth,

all things are vanity! (Ecclesiastes 12:1, 5-8)