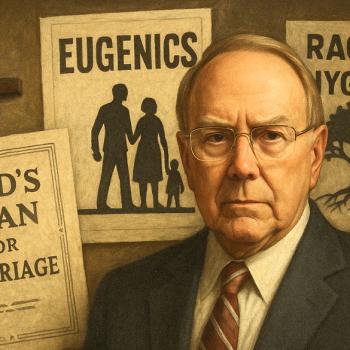

The first church I attended went through a huge split just before I arrived. Many were leaving because the church was pushing Gary Ezzo’s Growing Kids God’s Way curriculum. It was a parenting course that was heavy on discipline and scheduling the behavior of children until their naturally rebellious spirits were broken.

The curriculum philosophy echoed John Robinson’s 16th-century advice to his pilgrim parishioners, “And surely there is in all children . . . a stubbornness, and a stoutness of mind arising from natural pride, which must, in the first place, be broken and beaten down; so that the foundation of their education being laid in humility and tractableness, other virtues may, in their time, be built thereon.”

Ultimately, unruly children were the fault of their parents not being firm disciplinarians. Many people unhappy with this curriculum’s tone decided they couldn’t stay in a church where this was the driving philosophy behind parenting.

But this curriculum has sold hundreds of thousands of units. Its popularity shows just how much the Ezzo parenting philosophy jives with the evangelical view of human nature and authority.

Western Christianity and authority

From governments to businesses, western people are enamored with authority. They’re always looking for a defined chain of command. Power is about a position, and it’s essential that everyone understands and respects structures of dominance.

It’s not much different in the church. Clearly defined structures of authority are part of nearly every church model. In some, the pastor reigns supreme or leads with a team of elders. In others, the pastor rules the congregation with authority bestowed upon him from a distant ecclesiastical bureaucracy. Heck, even the Christian family, as one finds in Ezzo literature, is defined by its authoritarian bent—we call it “headship.”

It’s impossible not to filter Scripture through the context of our social structures. When we read biblical injunctions about leaders and overseers, we frame them through our cultural context. We see something about authority, and we think, “Oh, I know what that is.” Even when Jesus tells us that, in his economy, leadership is humble servanthood (Matt. 20:26, Matt. 23:11, Mk. 9:35, Mk. 10:43, Lk. 22:26), we still think, “Oh! A leader is someone with authority who helps sweep the church parking lot.”

To make matters infinitely worse, God operates within our power matrix. We simply take our understanding of what authority looks like and make it bigger and grander. In our minds, God wields power like we do, only more so.

It’s no surprise that, in an age of feudalism and kingly authoritarianism, a theology of God’s sovereignty would require that he be in complete control of everything. In contrast to the authority of kings and popes, God would need to be seen as an authority above all other authorities—controlling every event in the world.

Our context isn’t the only context

The supremacy of Western culture—and its power structures—are so ingrained that we struggle to comprehend things outside of their scope.

We tend to see the world broken down into variations of three dominant systems: capitalism, communism, and socialism. While all of these function in entirely different ways, they’re still are organized by a social hierarchy and maintained through some authoritarian construct.

Tribal cultures turn this view of the world upside down. In his book The People’s History of the United States, historian Howard Zinn talks about the life of the Iroquois:

In the villages of the Iroquois, land was owned in common and worked in common. Hunting was done all together, and the catch was divided among the members of the village. Houses were considered common property and were shared by many families. The concept of private ownership of land and homes was foreign to the Iroquois. A French Jesuit who encountered them in the 1650s wrote: “No poorhouses are needed among them, because there are neither mendicants nor paupers. . . . Their kindness, humanity and courtesy not only makes them liberal with what they have, but hardly causes them to possess hardly anything except in common.”

It’s incredible how much this sounds like the society the first-century church created as “all who believed were together and had all things in common. And they were selling their possessions and belongings and distributing the proceeds to all, as any had need.” (Acts 2:44–45)

When folks talk about passages like this one from Acts 2 in the church, people typically ask “should the church practice socialism?” This is a question that seeks to apply a western lens to a scriptural problem. What we see in the early church isn’t a modern political or economic structure being inflicted upon people. It’s an almost tribal reality birthed out of a shared experience and kinship.

Our cultural structure requires authority

Individualism is one of the most beloved things about capitalism. The idea that if people are left alone to pursue their interests, they’ll inevitably do good and share their resources. As some do well, society, as a whole, benefits. One can argue the truth of that sentiment.

This individualism leads to the problem of encouraging autonomy while promoting social order. Every group of people arranged into a community—government, businesses, churches, clubs—requires an enforced structure. In a world which places such a high commodity on individuality, authority needs to be strong and unflinching. And people need to be taught to respect and submit to it.

As UCLA historian, Gary Nash explains, the Iroquois had no reason for this structure:

No laws and ordinances, sheriffs and constables, judges and juries, or courts and jails—the apparatus of authority in European societies—were to be found in the northeast woodlands prior to European arrival. Yet boundaries of acceptable were firmly set. Though priding themselves on the autonomous individual, the Iroquois maintained a strict sense of right and wrong. . . . He who stole another’s food or acted invalourously in war was “shamed” by his people and ostracized from his company until he atoned for his actions and demonstrated to their satisfaction that he had morally purified himself.”

Again, this sounds so much like the early church where “church discipline” was merely a matter of being integrated within or disconnected from their community. It made sense for the Iroquois because they had no other tribe to join once they were excluded. In the same vein, the first-century Christians were centrally united in a local church, where could they go if excused from the body? There was one church in a city—they couldn’t just check into the church down the street.

The church didn’t require a forceful top-down model of authority. They enjoyed the blessings of shared community, common ownership, and “the favor of all people” (Acts 2:47), they’d be crazy to give that up.

Right-minded individuality

Communal living doesn’t require a complete loss of individualism. It requires a reframing of what it means to be an individual. Howard Zinn brings this out when he talks about Iroquois parenting (and it’s dramatically and demonstrably different than the Ezzo model):

Children in Iroquois society, while taught the cultural heritage of their people and solidarity of their tribe, were also taught to be independent, not to submit to overbearing authority. They were taught equality of status and the sharing of possessions. The Iroquois did not use harsh punishment on children; they did not insist on early weaning or early toilet training, but gradually allowed the children to learn self care.

All of this was in sharp contrast to European values as brought over by the first colonists, a society of rich and poor, controlled by priests, by governors, by male heads of families.”

It’s entirely possible to raise children with a strong sense of individualism within the loving context of community. The Ezzo’s “show them who’s boss” authoritarian model doesn’t have to be standard for Christian parenting.

There’s got to be something better

There isn’t an objective interpretation of Scripture. Even in our most vulnerable moments, we still read through the matrix of church teaching and personal experience.

Modern readers need to approach Scripture while dismantling (as best they can) the lens through which they perceive it. When I read about the early church, I can’t directly apply it to modern authority models. The world isn’t made entirely of structures I’m familiar with. If the first Christians had all things in common, it wasn’t because they were socialists. The Iroquois show us that there are civil structures beyond our political understanding.

Can the church completely dismiss the culture it finds itself in and become as it appeared in Acts 2? Probably not. The abuses we find in places like Jonestown illustrate the dangers of communal idealism. But there has to be something better than we have now.

The community life that we promote in the church isn’t much better than a social club. It features the same gossip, the same jockeying for social position and status, and the same rigid model of authority. We lack the imagination required to see New Testament Christianity through an entirely different social lens.