By Noah Lawrence

Special Counsel Robert Mueller is in serious jeopardy. President Trump’s replacement of Jeff Sessions with Matthew Whitaker follows past attempts to fire Mueller, and public language delegitimizing his investigation as “rigged.” At stake is Mueller’s ability to finish his investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. elections, into “any links and/or coordination between the Russian government and individuals associated with the campaign of President Donald Trump,” and into “any matters that arose or may arise directly from the investigation.”

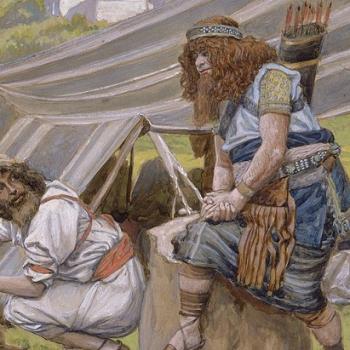

In Mueller’s mandate, echoes resound of another story of political authority and an independent figure who calls it to account, a story that lies deep within Abrahamic tradition and deep within the American mind: the narrative of King David, Bathsheba, Uriah and Nathan the prophet, in the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Samuel. David sees Bathsheba bathing on her roof; summons her to the palace; sleeps with her; and arranges the death of her husband, Uriah, by ordering his commander Yo’av, “Put Uriah in the face of the fiercest battling and draw back” (2 Samuel 11:15). In response, God sends Nathan to expose, censure and punish David. Nathan tells David a parable of a rich man who steals “the poor man’s ewe,” and then declares, “You are the man!” (2 Samuel 12:4-7; Robert Alter’s translations).

When Mueller’s work is seen through the lens of Nathan’s prophetic mission, as well as the lens of American legal-political history, a grave fact becomes apparent: safeguarding Mueller’s ability to do his job is not an ordinary political matter, to be subjected to the back-and-forth winds of usual politics; it is a moral imperative. It is necessary to secure a set of core moral values: equality of all before the law, responsibility for one’s actions, and the public’s right to the truth about those who lead them. This imperative and these values now call to the Trump Administration, to Congress, and to all of us.

When Mueller’s work is seen through the lens of Nathan’s prophetic mission, as well as the lens of American legal-political history, a grave fact becomes apparent: safeguarding Mueller’s ability to do his job is not an ordinary political matter, to be subjected to the back-and-forth winds of usual politics; it is a moral imperative. It is necessary to secure a set of core moral values: equality of all before the law, responsibility for one’s actions, and the public’s right to the truth about those who lead them. This imperative and these values now call to the Trump Administration, to Congress, and to all of us.

The King Is Not a God

In mining the Nathan story for values, where would one begin? NYU School of Law professors Moshe Halbertal and Stephen Holmes (full disclosure: both mentors of mine), in their book, The Beginning of Politics: Power in the Biblical Book of Samuel (2017), write that the foundation of the Book of Samuel is “the shift from ‘God is the king’ to ‘the king is not a God.’” A select group of humans wield centralized power, but those who do so are held to the same laws and ethics as everyone else.

This principle is eminently at work in the Nathan story. Nathan indeed treats the king as a person, not a god: Nathan holds David to the same standards as any other person, rather than allowing him, as king, to be above them.

The underlying moral value is that all people are equal before the law. And since people have a hard time holding themselves to a given standard, an outside authority is needed to hold them to it—especially those who have power.

David’s machinations also exemplify, say Halbertal and Holmes, the essence of corrupt use of power: the prime mover behind a wrongdoing uses power to spread around that deed’s elements among various actors and causes so that he or she does not appear guilty.

As Bible translator and commentator Robert Alter highlights, the Book of Samuel uses a common technique in the Hebrew Bible, repeating a word to spotlight a theme. The word “send” is repeated to illuminate the way David uses messengers and other agents to carry out the killing.

When a leader acts this way, it takes an independent figure to re-attach to him or her responsibility for those actions.

And the third value, truth exposed, emerges when the army commander Yo’av, in a narrative twist, leaks word of David’s wrongdoing through “an oblique dissemination” to an army messenger (Alter’s commentary on 2 Samuel 11:21). Similarly, David’s ultimate punishment is powerfully public: “For you did it in secret but I will do this thing before all Israel and before the sun,” God says via Nathan to David, contrasting the secrecy of David’s wrongs with the open nature of his punishment (2 Samuel 12:12).

Equal Justice Under Law

These values undergird not only ancient Israel’s founding, but also America’s. When the Declaration of Independence states, “all men are created equal,” and invokes “their Creator,” it relies on a power higher than any leader — not in a theocratic sense, as the First Amendment clarifies; rather, a standard to which even leaders are accountable. The Constitution’s structure is built on equality before the law: from its checks and balances regarding power; to the possibility of impeachment; to core shared civil rights, like the rights to “due process of law” and “equal protection of the laws”; and more. Its evolution, through amendments such as those involving Reconstruction, solidifies that equality further. The phrase, “Equal Justice Under Law” is literally carved in stone on the front of the Supreme Court.

Personal responsibility, too, is a bedrock American value. And democracy has always been premised on shared knowledge of truth, a principle well-evoked by Justice Louis D. Brandeis when he wrote, “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman” — employing the same metaphor of the sun that the Nathan story puts forth. These principles underlie the rule of law, or, per the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, “a government of laws and not of men.”

What makes these values specifically moral? Firstly, they touch on deep issues of right and wrong. They make normative claims that it is right that all people be treated equally, that people be held responsible for their actions, and that the public know truth about its leaders — and wrong for the opposites of these values to prevail. Just as crucially, these values concern how people treat one another, and how people feel and fare when others treat them in such a way. These values posit that it harms people to treat them unequally, to enable others to get away with wrongs and dodge responsibility, and to allow our leaders to conceal truth about transgressions. It is vital that we see through political distractions or complications to the fact that political acts can empower or hurt people; they can bolster or be destructive to moral values.

Robert Mueller is not a prophet, but he is calling the Trump campaign and Administration to account according to these values, and in so doing, he stands in relation to President Trump as Nathan stood in relation to King David. Mueller’s mandate is to actualize the value of equality under the law, by holding the officials of the Trump campaign and Administration to the same standards to which any American would be held. Further, he is to sustain the value of responsibility for one’s deeds by holding Trump officials responsible for theirs. And Mueller is to make public the truth about what they may have done.

Thus, the political act of firing Mueller would have moral stakes — it would be deeply destructive to the values central in the Nathan story, and in American history. It would spark both a constitutional crisis and a moral one.

We have seen what happens when these values are sabotaged and replaced with their opposites, as with President Nixon’s infamous dictum, “[W]hen the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.” We must not allow our country to go this way again. Or worse; at least Nixon ultimately heeded the Supreme Court.

Moral Values in Political Practice

It can be challenging to deduce political steps from fundamental values, because the latter should not be politicized. Yet what purpose do values have if not to teach us how to act? And what is the political process if not a way society comes together to act? Sometimes the result is clashing proposals, each stemming from articulated values. But sometimes the result can be trans-partisan, as it should be in this case.

What do these values mean in practice? First, Acting Attorney General Whitaker must not fire Mueller, or Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, who appointed Mueller and has overseen his investigation. Indeed, Whitaker should recuse himself from overseeing Mueller — “[g]iven his previous comments advocating defunding and imposing limitations on the Mueller investigation,” as Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-New York) said; and given the “highly irregular and unacceptable” situation of “[r]eplacing the Attorney General with a non-Senate-confirmed political staffer,” as Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-Connecticut) said. (Full disclosure: I have previously worked for Blumenthal.)

President Trump must not use his firing power over the Attorney General’s position to engineer a neo-Saturday Night Massacre. The Administration must not hamstring Mueller in other ways, including defunding his investigation. And the distortions, distractions, and delegitimization that have characterized the debate over Mueller must not continue.

That is what must not be done — what, in turn, must be done? First and foremost: In the next attorney general’s confirmation hearings, senators must demand that he or she pledge not to fire Mueller or Rosenstein.

Both houses of Congress ought to pass the Special Counsel Independence and Integrity Act, introduced in the Senate this past April, and now enjoying a renewed push by senators like Jeff Flake (R-Arizona) and Chris Coons (D-Delaware), but blocked by Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky). The Wall Street Journal summarized the bill thus: “[T]he bill would enshrine into law a Justice Department guideline that a special counsel can’t be fired without cause. In addition, it would give special counsels a 10-day window to challenge a dismissal in federal court. It would also require special counsels to report to Congress at the end of their investigations.”

Odds of the bill’s passage are slim; being signed into law by the President, virtually zero. But this bill should be fought for, as this process would help shape our culture’s character. To see members of Congress endeavoring to pass a bill that defends the core values of equality under law, responsibility for one’s actions, and truth about our leaders; to see them not bowing to attempts to block that bill but pressing on — that matters.

Furthermore, the bill’s relatively strong bipartisan support by the standards of this deeply divided era is highly significant. When the bill was introduced in the Senate, its sponsors included two Republicans and two Democrats (Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-South Carolina), Cory Booker (D-New Jersey), Thom Tillis (R-North Carolina), and Coons). Additional supporters include Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Flake. And the bill passed the Judiciary Committee. These senators of sharply divergent political views have united on this issue, signaling its gravity and urgency.

Choosing at a Moral Crossroads

Our country is standing at a moral crossroads. All that rests on Mueller’s investigation — whether the public will ever know what really happened in the election and its aftermath; whether those who may have committed wrongdoing, including those now in power, will ever be held accountable — depends on which way we proceed. The underlying values of our society will be altered by which path we take. With each day, new developments and revelations make these stakes painfully clearer.

We must choose the direction of protecting equality, responsibility, and transparency. We need a figure who can hold our leaders to the same standards to which any ordinary American would be held. We need a figure who can unearth Russian election interference’s full extent, and the extent if any to which Trump campaign officials coordinated with it. We need a figure who can ascertain the prime mover in any such wrongdoing, and who knew about it and did not stop it. We need a figure who can determine whether attempts by officials to stymie this probe constitute obstruction of justice.

And we need a figure who can point to such officials and say, “You are the man.”

Noah Lawrence is a legal scholar and a student at New York City’s Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT) Rabbinical School; its mission is to train Orthodox rabbis who are “open, non-judgmental, knowledgeable, empathetic,” and committed to “the larger Jewish community and the world.” Previously, he worked in law and politics, including for Senator Richard Blumenthal, at the Israeli Supreme Court, and at the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague.

Image source: UPI/Kevin Dietsch, Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)