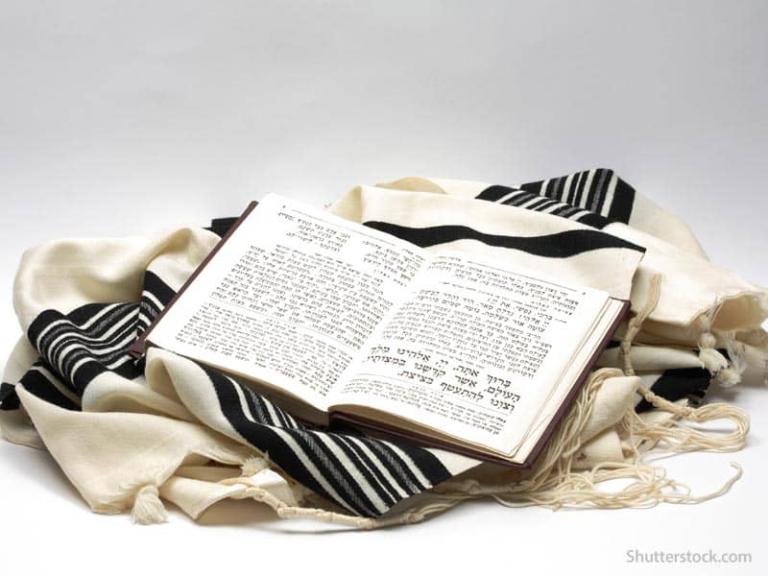

Judaism is one of the most ancient surviving religions on the earth today. Its age, cultural heritage, and deep ritual practice are rivaled by only a few sacred traditions. And, as the parent of the two other Abrahamic religions (i.e., Christianity and Islam), Judaism’s impact on the world has been multiplied many times over.

Quite literally, more than 3.5 billion humans today have been directly or indirectly impacted by this ancient faith tradition.

Denominational Diversity

While the Biblical account of God founding of the Jewish faith through Abrahm presents what might be considered an initially unified faith; by New Testament times, one can see present a denominationalism which did not exist in Judaism’s earliest days. Today, it is even more partitioned, with various groups having their own rites, ritual approaches, and even beliefs.

For example, media depictions of Judaism often highlight those from the Modern Orthodox and Haredi movements. Among these groups we often find the most observant Jews, focused heavily on living the 613 commandments given in the written and oral Torahs. While there are many who practice one of the “Orthodox” denominations, they represent less than a third of all Jews.

In comparison to the Orthodox branches, Conservative Judaism (sometimes referred to as “Masorti” or “traditional”) is a movement that adheres to much of Jewish law (or “Halacha”) but also allows for adaption of practices as times and beliefs change. Reform Judaism, on the other hand, is typically considered the most progressive denomination of modern Judaism, allowing for a great deal of autonomy in belief, practice, ethics, etc.

A percentage of Reform Jews identify as agnostic. The Reconstructionist movement is also very progressive. However, it is small and often considers itself post-halachic (or beyond commandments or law). This group typically focuses more on Jewish culture and history—celebrating one’s “Jewishness”—and much less on theology or even a belief in God.

Indeed, a high percentage of those in this tradition are agnostic or atheist. (Many Humanistic Jews would fall under this branch.)

The number of Jews worldwide (as of 2025) hovers around 15-16 million. Less than half live in Israel, and the United States has the second-highest Jewish population in the world. In the 21st century, Judaism is no longer growing. Indeed, if anything, it is contracting in size—as are most faith traditions today.

There are several factors influencing this worldwide decline per capita in the number of Jews, and Jewish observance.

Among those are the following:

Antisemitism

While there have been numerous periods in history in which the Jewish people have been heavily persecuted, in the 20th and 21st centuries there has been a major resurgence of antisemitism, particularly in the United States—but globally as well. From the Nazi Holocaust to the October 7th massacre, certain non-Jews have perceived and sometimes depicted Jews as a threat to various global concerns, from the economy to the plight of the Palestinian people.

As a result, some previously practicing Jews have sought to hide or reject their religious identity for the sake of safety, employability, just treatment, and basic inner-peace.

Assimilation

Another chief challenge affecting the state of Judaism in the United States (and globally) is assimilation and inner-faith marriages. A significantly high rate of Jews, particularly outside of Israel, marry outside of the faith.

(Over 70% of non-Orthodox Jews in the U.S.)

This almost always leads to a deluding of the practice of the faith within the home, and the rearing of the children in no faith or in another faith tradition (typically Christianity). That leads to a weakening of the “Jewishness” of the next generation and stunts the passing on of Jewish traditions, beliefs, and culture.

In addition, since the largest number of Jews today are theologically progressive, fewer and fewer Jews are practicing their religion in the “traditional” or “ancient” ways, leading to less religiosity and a loss of traditional beliefs and practices among contemporary Jews.

Cultural vs. Religious Identity

Like so many other religions today, Judaism is experiencing a decline in religious engagement generally. More and more Jews consider themselves “culturally Jewish,” but not religiously so. Thus, they are less prone to attend synagogues, commemorate the various Jewish holidays, and less inclined to make their Jewish identity their “primary identity.”

The divisions between the various Jewish “denominations” have had significant impact as well. Some in the most observant denominations question the “Jewishness” of those in progressive and non-observant traditions.

Similarly, those in the more theologically progressive denominations (in the U.S. and Israel) tend to look down on the Haredi (or “Ultra-Orthodox”) Jews. In Israel, conflicts over issues like religious authority, military service exemptions, and civil rights, are common, and this leads to a lack of unity among Jews, which leads to a breakdown of the faith and how it is conveyed to the rising generation.

Birthrates among observant Jews are increasingly declining. The several Orthodox traditions still tend to have larger families, but those in the theologically progressive denominations are not reproducing. As a consequence, Judaism is shrinking in size with each successive generation. Those lower birthrates, coupled with their lack of effort to proselytize, have had disastrous consequences for the vitality of the faith.

Connection to Israel

Unlike Christianity, which (in the modern era) really only has a textual tie to the Holy Land, Judaism is much more connected to the region of Palestine, the nation of Israel, and the former Temple Mount.

However, younger Jews—particularly those born or reared in the United States—do not have this same religious, spiritual, or emotional connection to that part of the world. Indeed, many U.S. Jewish youth tend to feel disconnected from the Israeli State, as well as manifesting a measure of disdain for the Israeli government.

Consequently, many become anti-Zionism and antagonistic toward those of their own faith.

Language and Cultural Practices

For Jews who grow up in the U.S., many never learn Hebrew or never become fluent in it. They are less familiar with traditional Jewish foods, cultural practices, and even Jewish forms of education (more common in other parts of the world).

As a result, they become very Westernized in their views on each of these things. What was once very much a part of the faith feels distant and foreign, and is not celebrated or embraced, but sometimes even shunned or ignored.

Geographical Distribution

Unlike those living within Israel’s concentrated Jewish population, American Jews are often forced to live in major metropolitan areas in order to enjoy a thriving Jewish community and all that provides. If one settles in a part of the United States where there isn’t a strong Jewish presence, many of the traditional components of the faith’s practice and culture are lost.

Even if one does live in a hub for Jews, like New York or San Francisco, many synagogues and Jewish institutions struggle financially, especially in communities with declining Jewish populations. Thus, it costs a lot to support and maintain those needed institutions, and sometimes they are lost because of the exorbitant costs or through declining Jewish population.

The bulk of Jews in the United States today are part of one of the non-Orthodox denominations. Indeed, only around 10% of American Jews (in 2025) identify as Orthodox (i.e., Modern Orthodox, Haredi, or heavily observant). About 40% identify as Reform (which can oftentimes feel rather “watered down” to Orthodox Jews).

As many as 35% of American Jews consider themselves only “culturally” Jewish but are largely non-practicing. And a very small percentage of U.S. Jews fall into the Conservative movement—as low as 15%. Thus, even though the United States has the second largest Jewish population in the world, the majority of Jews living in the U.S. are not heavily “into” what we might describe as the more “traditional” or “observant” form of the Jewish faith.

Conclusion

Judaism in the United States is perhaps representative of Judaism throughout the diaspora. For all the good being done by Jews globally, their faith tradition is struggling greatly throughout the world—and the U.S. is no exception to that.

Many factors are contributing to the decline, but Western culture combined with the progressive theology of most American Jews are perhaps the two greatest threats to the Jewish religion in America.