We recently met a man in town named Suleiman. He is a Muslim background believer who disciples young refugees and immigrants in East Africa, preparing them for life and ministry back home in their Islamic communities.

We recently met a man in town named Suleiman. He is a Muslim background believer who disciples young refugees and immigrants in East Africa, preparing them for life and ministry back home in their Islamic communities.

He has a fascinating back story. As a young child he was well-acquainted with the traditional African religion of his parents and grandparents. In early adolescence he dabbled in youth events at the local church. But when war came to his home he was sent to the safety of a city further North, and it was there, watching men in white robes walk to the local mosque with their green holy books in tow every Friday that he began to seriously pursue his deep hunger for God.

Suleiman became a devout Muslim, a faithful student of the Koran, an avid learner. And though he wasn’t always satisfied with some of his teacher’s answers to his questions, he continued to ask them and further his religious education.

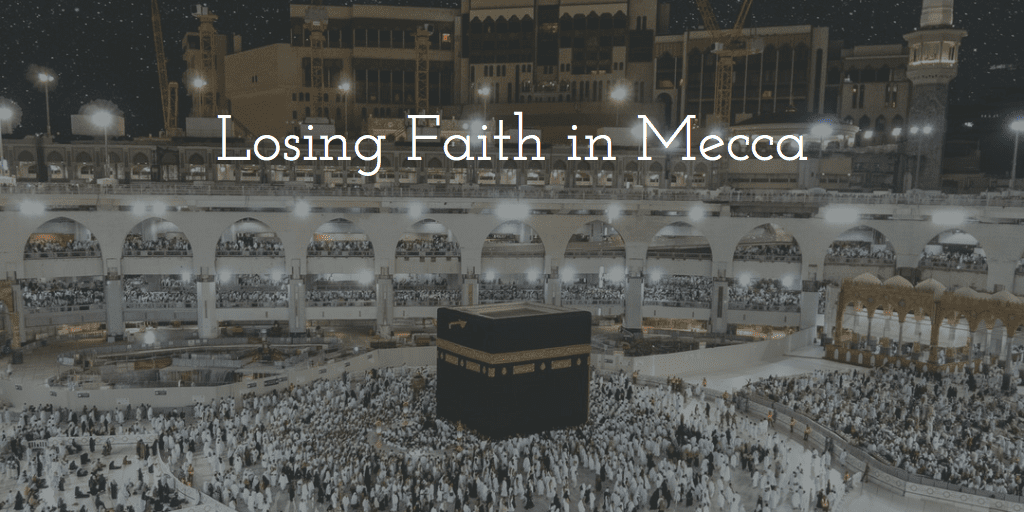

His spiritual journey within Islam culminated on Haj, the pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca. One of the most significant moments of Haj comes when pilgrims circle the Ka’ba, the holding place of a sacred black stone. Suleiman began this ceremony and as he moved in a great sea of humanity swirling faithfully around the Ka’ba, questions began to bubble to the surface of his mind. Questions that he then posed to his spiritual guides. What are we doing? Why are we doing it? What does this mean?

Suleiman says that his questions were met with gentle rebuke. The warning not to ask so much. He was shushed.

And in that moment, at the pinnacle of his religious experience, Suleiman came to the conclusion that what he was doing wasn’t worship to the God of the patriarchs but was merely walking in circles around a rock.

It was there, in arguably the single most spiritually significant place on the planet to the largest number of people that Suleiman lost his religion.

And in exchange began discovering the heart of God.

* * *

So, I am just going to come out and say it: I really love Muslims, both the ones that have come to know Jesus and the ones that have not. My best friends in high school were Muslims (one still sends me care packages from time to time), my swim coach was a Muslim, and over the past decade in North Africa I have been a part of communities deeply impacted by Islam and I have been shaped by that in ways I would never trade.

For some people this gives me credibility. For others, it makes me highly suspect.

Either way, I have found that interacting with Muslims has been an incredible catalyst for my own spiritual growth. Sometimes that experience is unsettling in a way that deepens my roots into my own heritage. Sometimes that experience is unsettling in a way that stretches new branches, like when I witness examples of Christ-like love modelled to me by people who don’t even know him. But perhaps more than anything my experience as a Christian living in an Islamic context has felt a whole lot like standing up against a pane of glass. At first I thought I was gazing through the glass at the culture, politics and systems of faith of another people. But the longer I stand here, the more difficult it has become for me to distinguish between the image beyond the glass and the one reflected back in it.

Which I think is why Suleiman’s story impacted me so much when I first heard it. Because it reminded me of all the times I have been to Mecca.

In my early twenties it was being at a Christian college (one that even played music from a tower to call us all to prayer once a day, no less). It was conservative in its heritage, though my favorite professors pushed the seal of most of my envelopes. I attended one of the healthier churches in town, the kind with the cool preacher that made spiritual growth entertaining. I got As in my mandatory Bible classes, didn’t break the school’s no alcohol policy in any meaningful way, wasn’t sleeping with my boyfriend.

Flash-forward a decade and Mecca has been working as a Bible translator in North Africa. I’m officially a third generation missionary, (which is gotta count for something right?). I help teach people to read, we do family devos most nights, I have a cool Facebook profile picture of me and lots of cute refugee kids, my daughters don’t seem too screwed up despite the whole third generation missionary kid thing.

Mecca.

I bet you know it too. Maybe it’s Sunday mornings in a church building, teaching a Bible class, kids who don’t cuss, marriages intact, reading (or very intentionally not reading) whatever book Jen Hatmaker or Rob Bell just wrote. Or maybe it’s less measureable in the stuff we do or don’t do, but more about what we believe. The really well-developed theologies that confirm our world views, indorse whatever privileges or powers we hold in society, and help us sleep well at night because they completely validate who we vote for. All those well-established systems of belief we ascribe to because they have our backs.

Of course, we never take our blessings for granted. We know not everyone marries the right person or can go to a big church in Dallas. Not everyone has the time to get their theology of everything all lined up. Not everyone can be a missionary (or minister), or college-graduate or an American, God bless them.

But seriously, secretly, isn’t it such a relief that we are?

It is a never-ending source of unease to me that the demographic most targeted by Jesus in warning are mainstream religious folk. People who have a lot going for them in the existing power dynamics of the day. People like me, and probably you.

In Matthew chapter 2 Jesus is talking to a crowd of just such people, people who liked to pull out their spiritual/racial/family history get-out-of-jail-free cards. And he calls bull crap. He looks them in the eye and says, “You see those rocks over there? I could turn them into a bunch of middle-class American church goers who vote correctly if that was what I was looking for. That means nothing to me.”

Or something like that anyway.

You see, the problem is our holy cities are so much safer to live in than Jesus is. They keep us comfortable and protect us from actually having to encounter God. Holy cities tend to be built on things like power, answers, security and knowledge. And with Jesus’ preference for the powerless, the doubters, the dirt poor, the messed up, the ones way outside of the city gates….well, he is a lot more dangerous to deal with.

If you are stepping into this new year full of hope and energy, God bless you. I hope this year is everything you are dreaming it might be. But as you step forward, it might not hurt to check and see if there are any rocks you are walking in circles around and calling holy.

And if you are staggering into the new year, still reeling from the battery of the last twelve months, God bless you too. If Suleiman’s questions sound like yours – What are we doing? Why are we doing it? What does this mean? – take heart. They are questions worth asking.

Suleiman went through three religions before he found God. It’s worth taking a look to see if ours is keeping us safe from Him as well.