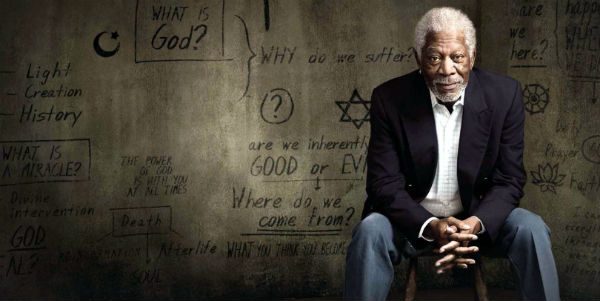

In the next episode of “The Story of God,” airing Sunday, April 17 at 9 p.m. ET/PT, on National Geographic Channel, host Morgan Freeman goes in search of the nature of the Divine.

In the next episode of “The Story of God,” airing Sunday, April 17 at 9 p.m. ET/PT, on National Geographic Channel, host Morgan Freeman goes in search of the nature of the Divine.

He makes a warm and charming examination of polytheistic Hinduism and Navajo religion, and a lyrical examination of Islam, including parts of it that originated in its predecessors, Judaism and Christianity, while speaking as if the notions were unique to Islam.

In this episode, the only representation of Christianity is a perfunctory visit to Joel Osteen’s Texas megachurch.

So, if you’re looking for the Catholic sense of divinity, oddly, it’s best expressed in some parts of the segment on Islam, but with Christ as the the Son of God obviously removed from the picture. Also, the idea of the infinite God becoming both fully divine and fully human — the very core of Christianity — is not really discussed, unless you count Osteen’s presentation of Christ as a “friend” (which, of course, He is, but also so much more than just your best buddy and business booster).

National Geographic Channel posed these two questions to bloggers participating in this ongoing look (click here for an earlier installment) at “The Story of God”:

How has the perception of God changed over time?

Monotheism vs Polytheism – does your worldview impact your daily life?

I’m no theologian — just a Catholic revert who’s spent most of my life focused on storytelling, on the screen and on the page. But I have also sojourned among the modern pagans, and studied many mythological systems, along with the writings of Joseph Campbell, who tells us much about how humans have told stories about gods and heroes.

But, see, here’s the thing … humans created those stories, as wonderful and insightful as they are. They are told in a human manner, featuring characters, even the gods, who act in recognizably human ways. The stories resonate deeply, because they reveal much of how people experience the world and relate to each other and to the unknowable.

After returning to the Church, when I dug into the Catechism and the Scriptures, coming at them nearly with fresh eyes, what struck me most was the strangeness of the stories, from Abraham to Christ. In the West, we’ve become so accustomed to the Biblical narratives, they’re so interwoven into the very fabric of our culture and literature — whether you’re a believer or not — that we take them almost for granted. We are like fish who don’t know they’re wet, swimming in a sea of quotes, aphorisms, poetry, characters and ideas born in the Word.

Taken in from the outside, though, they are odd tales indeed. As I read the Passion narrative and the Acts of the Apostles in particular, it became obvious to me that these aren’t the kinds of stories people concoct when they want to start a new religion. People generally make themselves look a lot better and smarter and braver than the Apostles did, if they expect folk to trust and follow them. I was looking at flawed men and women, telling stories that were confusing and confounding and often unflattering, because that’s how it happened, and that’s how it had to be told.

A lot of what makes heresies so appealing is that they correspond more to how we think God should be, in our human way of envisioning Him. They’re seductive and make sense on the surface, but ultimately, “the appalling strangeness of the mercy of God,” as novelist Graham Greene put it, is missing. Because God shouldn’t conform to what we want; we need to conform to what He wants, as best as we can discern it — and that’s seldom the most obvious path in human terms.

The God of the Judeo-Christian world — to paraphrase a talk I heard today from L.A.’s Bishop Robert Barron — is not a creature or being among other creatures and beings. He, if you want to use that pronoun, has no sex and no form (but Jesus Christ was definitely male; make no mistake about that). God needs nothing from us, but wants everything for us. God is not part of existence; He is existence itself, the very energy and fabric and, well, everything, that brought everything into being and holds it all together.

God doesn’t exist outside reality; He IS reality.

In the Christian view, in His wisdom, God saw that this was not enough for us. So, He came down to His people, became one of them for a time, lived among them — not because He needed some kind of a crash course in what it meant to be human, but because we, as creatures of flesh and spirit, needed a God with hands and a face (even if, Shroud of Turin notwithstanding, we don’t know the details of that face).

The idea of being fully God and fully human is a tricky and shocking proposition. It didn’t set well with most of the Jews at the time, or, much later on, with the Muslims. Even between the Catholic and Orthodox lungs of the Church, sorting out the details of how the Trinity of God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit works has been fraught with difficulty.

But why should we think that thinking about God would be easy? You might as well ask your dog to describe the manufacturing process and nutritional components of his kibble. Although, as Freeman demonstrates in a segment in which science shows that the frontal lobes of believers light up when they contemplate God, we’re still trying to grasp infinity with a blob of wrinkly grey matter stuck inside our heads. This stuff’s hard.

For a polytheist, the idea of divinity is fragmented, existing here and there, in this deity and that, tied to this people or that, on this mountain, in this lake, or up this tree. Christians, too, have their holy places and places where a person may feel the presence of God most powerfully, but if all the church buildings in the world imploded tomorrow, along with all the sacred art, it would be a tragedy for mankind, but it wouldn’t be the end of the Church. She is the Bride of Christ, and all the baptized breathing, eating, sleeping and worshiping within her are the living Body of Christ.

God became Man and walked with us, but was no less the immanent, omniscient God of the Universe for it. He lived, taught, suffered, died and rose again not because He needed to, but because He had compassion for His children, and wanted them to know, in a concrete way, that He understood, that He conquered our bodily death, and that one day, we would hold the hand and touch the face of God.

Image: Courtesy National Geographic Channel

Don’t miss a thing: head over to my other homes at CatholicVote and the Faith & Family Media blog, and like my Facebook page; also like the Patheos Catholic FB page to see what my colleagues have to say.