What It’s About: This is a famous and very consequential scene from the time just after the exiles had returned from Babylon. It narrates a kind of second constitution of the law, in which the people (led by Ezra) turn back to the law of God through a dramatic reading of it aloud in their midst. The scene is (somewhat unrealistically, maybe) one of rapt silence, in which all the people dutifully and faithfully hear the law proclaimed aloud. This is an important symbolic moment for a lot of reasons. Think about the circumstances in which this scene takes place: the temple is in ruins, the people have been scattered, and hope has only just recently been rekindled. The trauma of the exile must have been close at mind, and not least the theological trauma of seeing God’s house destroyed. So this is not only a moment of hopefulness; this is a moment of hopefulness that is centered on finding God not in the temple, but in the law. This moment is a pivot point for the people’s view of God, and where God resides.

What It’s Really About: This is a turn toward the book. Israel’s religious identity had long been literary, of course; stories had been told and law recorded before this moment. But this is a real symbolic turning point, in which the place where God had resided was in ruins (literally) in the background of a reading that placed God in a new context. God lived in the book, not in the temple (necessarily); obedience to God lived in following the law, not in rituals at the temple.

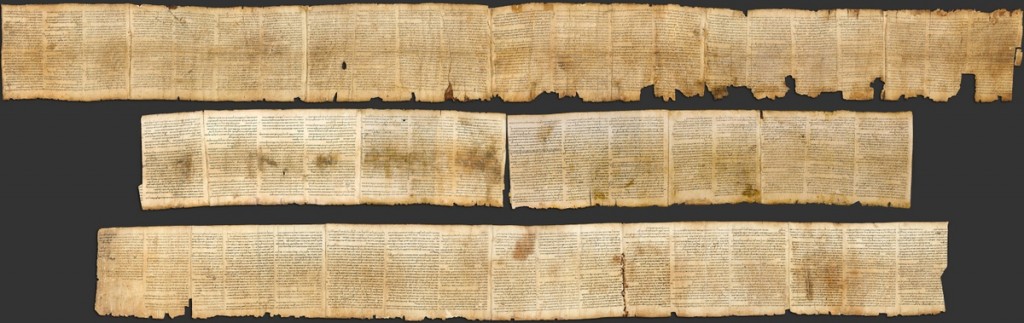

What It’s Not About: The word “book” here is multivalent. This was a period long before the invention of the codex, which is what we think of as the “book.” Ezra is reading from a scroll here–perhaps one spirited away from the destruction of the temple a generation before. A scroll was (and is) a very precious thing, holding much symbolic as well as economic value. Sometimes you hear about a church that has caught fire, but which has had its pulpit bible miraculously survive. This is an analogous situation; the survival of this scroll must have given a lot of hope to the people, and hearing it read aloud all the more so.

Maybe You Should Think About: There is so much anxiety these days about the American public’s exodus from churches. A lot of sanctuaries sit empty on Sundays, and explanations abound. One of the most common ones is that people are turning toward a more personalized, less institutional mode of faith. If that’s true, then there are real parallels to this passage from Nehemiah, in which the temple building is no longer a center for religion (because it is in ruins), so people turn to books. It’s an imperfect analogy, but maybe it can give us hope and insight into the plight of Christianity in the United States today.

What It’s About: This is a very famous passage from scripture, Paul’s analogy of the body of Christ. As I said last week, the 11th, 12th, and 13th chapters of this letter really have to be read together, as they form a single argument for unity within the church. This section comes between Paul’s admonitions about the Lord’s Supper and his later discourse on love in chapter 13. Here, Paul puts forth a vision for community as a thing that holds difference in tension. Being different from one another is not a “bug,” in tech language, it is a “feature.” The hands are different from the feet, and the pancreas different from the eyes, precisely so that the body can function.

What It’s Really About: There is an interesting book by Dale Martin called The Corinthian Body that argues that there is a certain view of the body behind Paul’s letter. I think there is truth to that; Paul is obviously appealing to an understanding of the way the body works that explains its functioning in terms of difference. (There are lots of other body references in the letter that the book deals with too). Paul, though, clearly thinks that his readers will resonate with his casting of the community in terms of a body. And, indeed, it has been an effective metaphor to this day.

What It’s Not About: The occasion for chapters 11-13 must be pride and arrogance. Those human traits lie behind the whole section; that is why Paul comes up with this analogy. His concluding section of this passage, then, is a forceful reiteration of that. Verses 27 through 31 point the way to his answer to these problems of pride and arrogance, which he will give in chapter 13.

Maybe You Should Think About: The question for a passage like this is always how it translates into the 21st century. In an era of professional clergy and seminary educations, how does this work? In a time of dwindling church attendance, does this still hold? How do we hear Paul’s body of Christ analogy today?

What It’s About: This is, like the Nehemiah and 1 Corinthians texts for today, a very famous story. It is the tale of Jesus returning home, to Galilee and to Nazareth specifically, and teaching in the synagogue. This story is told in pretty distinct ways by different gospels, but in Luke the emphasis is the content of the scroll (scrolls again!) he is given to read. It is a scroll of the prophet Isaiah, and the section Jesus reads turns out to be a kind of a mission statement for his ministry. Luke sometimes adds an emphasis on social justice where other gospels leave it out, so it’s not surprising that here we get a radical vision of Jesus’ purpose: freed captives, liberated oppressed people, seeing blind folks, good news to the poor.

What It’s Really About: This is a brilliant storytelling move by Luke, who is able to contextualize Jesus in two ways: as a doer of good, and as someone standing in the tradition of the prophets. It’s a crafty way to have Jesus look messiah-like, in a way people probably didn’t expect.

What It’s Not About: This is probably not a historical account. That shouldn’t scandalize us or even surprise us; Christians, like everyone else in antiquity, told stories in a way that was designed to convince people, not convey facts in an accurate way. (The concern for factuality as the only measure of truth is really an artifact of the Enlightenment). Scholars debate whether synagogues would have been widespread in the period of Jesus’ life, and certainly whether a small town like Nazareth would have had one, and whether they would have been able to afford an Isaiah scroll. And then there is the matter of Jesus’ literacy; again, scholars debate that. But: it doesn’t matter. The passage isn’t about being an Associated Press dispatch. It’s about telling who Jesus is, and it succeeds at that brilliantly.

Maybe You Should Think About: To what degree is this “mission statement” that Jesus read in the synagogue still the mission statement of the church? And if it’s not…why not?