What It’s About: This Sunday is Transfiguration Sunday, and so the Hebrew Bible text for the day harkens back to a comparable event from Exodus: Moses descending Mount Sinai after receiving the law. Matthew, in particular, draws a strong connection between the life of Moses and the life of Jesus, but the transfiguration story is present in all of the synoptic gospels. This story from Exodus is a pretty interesting one, because it gives us some insight into how the Israelite people thought about their God. Moses had been there talking with God, and he had been changed by the experience, so that his face shone. But Moses himself was unaware of this, I guess because he didn’t have a mirror handy. Everyone else was aware of how his encounter with God had changed him, but Moses himself was oblivious.

What It’s Really About: Most scholars see the origins of the Israelite God (who carried the personal name YHWH) in the common Levantine storm god or mountain god traditions. Those kinds of gods were well known in the area, since storms brought much-needed rain, and storms often gathered at mountaintops. A friend of mine actually just finished a very thorough and very excellent dissertation on this topic; I hope by next Transfiguration Sunday to be able to refer you to her book.

What It’s Not About: One of the most persistent and stupidest mistakes in bible translation is in this passage. The word translated “shone” here means something like “rays,” probably a reference to the way light shines out from behind a cloud (and probably connected to that storm god beginning). But some ancient translators misunderstood the word, and translated it to read that Moses had horns. That began a long tradition of depicting Moses with horns, and long traditions of popular belief that Jews had horns, and of course anti-semitic associations of Jews with devils, etc. I hope it doesn’t need to be said, but Jews don’t have horns, and bible translation matters!

Maybe You Should Think About: What’s the distance between that Levantine storm god, who can be met high up a mountain, and Jesus ascending the mountain in the Luke passage below? And what does this episode from the life of Moses do to change the story in the interim? Is there any trace of the storm god in the gospel accounts? How much, exactly, are we supposed to think of Moses when we read the story of Jesus’ transfiguration? Is the same thing happening to both of them, or is Jesus’ transfiguration somehow different from the change in Moses’ appearance?

What It’s About: This is a tricky text. It’s here because it references Moses’ descent from Sinai, and it therefore matches the day’s other texts. But I fear this text muddies things rather than clears them up; Paul’s interpretation of Moses’ face and his subsequent veiling makes a complicated text more complicated. Paul sees the veiling as a metaphor for incomplete knowledge (which is something of a theme of his in 1 Corinthians, as we saw in last week’s reading of chapter 13). Jewish persons, Paul seems to be saying, have an incomplete perspective until and unless they view things in light of Jesus.

This is the kind of argument you might expect a Jewish person (as Paul was) to make to gentile Christians like his audience in Corinth. He might be answering, implicitly, why these gentile converts shouldn’t just be Jewish instead. There is something important about Jesus, he is claiming. But it’s worth pointing out that Paul is not altogether consistent on this matter. Elsewhere in his writing, especially in Romans, he defends Judaism as a holistic religion, and he seems to think that Jews don’t “need” Jesus. Jesus is a device through which God can open salvation to the gentiles, but Jews of course never had any trouble with salvation. They had the covenant with God from Exodus (among others). Ultimately, Paul is speaking to gentiles as a Jew about the direct availability of God. These gentile Christians in Corinth do not need to go through Moses; they can go directly to God.

What It’s Really About: The single most important thing to remember when you read Paul’s letters is that he is not writing to us. When we read Paul, we are always reading someone else’s mail. Paul’s letters are always occasional; they always have a reason for existing. They are not theological tracts, they are letters, written to address specific issues in a specific time and place, that we have found useful and true enough that we have called them sacred texts. So, in light of all that, we always have to ask about his audience. As I mentioned above, here Paul is writing to gentiles. Paul makes a point of his ability to be all things to all people, and it’s notable how he changes his tune a little when he writes to a community with a stronger Jewish presence (Rome) or a weaker Jewish presence (Corinth). He is tailoring his words to his audience. And we are not his audience. So I implore you not to take passages like this one as a license for anti-semitism; don’t preach this as if Paul denigrated Judaism, because he didn’t–not if you think systemically about his thought. He valued it, and saw it as a going concern, and placed himself within that tradition.

What It’s Not About: It’s not about us. This can never be forgotten when we read Paul’s letters; we are not his audience. And the “this very day” of verse 15 is not our day; that day is millennia in the past. We cannot simply import Paul’s words into the present without a careful consideration of their contexts and the reasons Paul would have had for writing them.

Maybe You Should Think About: This passage ends strangely. Remember, all section, paragraph, and even sentence breaks in the bible are artificial; Greek manuscripts of the New Testament have little in the way of punctuation, and certainly nothing that we would recognize as such. It has been up to scholars and clergy to make divisions based on sense; it’s always a judgement call to say where a paragraph or sentence ends. You can see that here; someone once thought that chapter 3 should end and chapter 4 begin within this passage, and so it’s divided this way. (Chapters aren’t in the Greek manuscripts either). But the lectionary prefers to keep 4:1-2 together with the end of 3, obviously seeing a unit in those verses. Still, those first two verses of chapter 4 don’t quite mesh with the rest. They are still about hiddenness and truth, but not in the same way, and it’s not clear how they relate to what came before. What does the “therefore” do, and what does “the sight of God” mean when put into context of the story of Moses going up the mountain?

One more thing to think about: it is a matter of some debate among scholars as to what, exactly, Paul knew about Jesus. He says almost zero about Jesus’ life and teachings (1 Corinthians 11 is the major exception), and proclaims “Christ and him crucified” as nearly the sum total of his knowledge. Some say that this is because Paul’s letters are occasional, and he just didn’t have much occasion to bring it up. Others say that there are moments where it would have made sense to bring Jesus’ biography into things, and that Paul foregoes those moments, and therefore he probably didn’t know much.

I side with those who think that Paul simply didn’t know very much about Jesus. This passage is a great example of that. Why would Paul not mention the Transfiguration at this moment? It would greatly bolster his argument, would it not? But he seems to be unaware of the story. This tells me that Paul, who lived in a time before any written gospel that we know of, simply was uninformed about the life of Jesus. That’s not surprising when you think about it, but it’s also very counterintuitive at first blush.

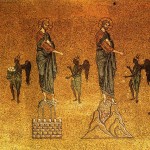

What It’s About: This is the transfiguration story, in which Jesus and a select few disciples ascend “the mountain” to pray, and experience some dramatic events. As noted above, this story is closely connected to the story of Moses ascending Mount Sinai to receive the law; Moses even makes an appearance (along with Elijah), a kind of Han-and-Leia-in-the-new-Star-Wars moment.

What It’s Really About: What is this really about? Different people have answered this in different ways over time. Adoptionist Christians pointed to this episode, and the “chosen” language in verse 35, as evidence for their position. Others see this as Jesus joining the Jewish all-stars, as another prophet and leader. And of course this looks forward to Jesus’ death and resurrection, as is made explicit in the text. This is a rich text, and it has given rise to a number of interpretations. The first interpretation, of course, is that of Peter, John, and James, who see this as something of an arrival point (and rightly so). They want to preserve the moment, set up shop, and hang out. But their impulse is immediately answered by an angry kind of encompassing cloud (back to that Levantine storm god imagery!), and they learned that they had to move on.

What It’s Not About: Verses 37-43 are optional, but they are interesting. The father speaks of his son, his only son, which is an echo of the voice from the cloud in verse 35. Luke was a careful editor, and it’s not likely that the two stories ended up beside each other by accident. We’re meant to glean something from the juxtaposition. This story also gives Jesus an opportunity to ratchet up the apocalyptic rhetoric, raising expectations of his journey to the cross. His “faithless and perverse generation” comment is harsh, and it probably builds on the disciples’ obliviousness up on the mountainside.

Maybe You Should Think About: What is at stake in this story? Why tell it, and why talk about it? More than most stories in the New Testament, this one requires care. You should have a sense of what you think it says, and what you think you want to say about it. This is because it is given to so many different interpretations, and the meaning, at the end of the day, is a little bit ambiguous. Is this pointing the way to Lent? Is it about Jesus’ identity? Is it about Jesus’ disciples and contemporaries as faithless and witless, in the same way the Israelites were at Sinai (the golden calf episode comes only a few pages before the story of Moses’ shining face)? Think about what this story is going to say, and how you want to help it say it.