There are lots of choices this week–which makes sense, because it’s a pretty big day in the life of the church. You have options at every point of the lectionary–in the text that is traditionally from the Hebrew Bible (which is supplemented with an Acts passage), the text that is traditionally from the epistle (ditto, with the same Acts passage), and the gospel text, which has a Luke/John choose-your-own-adventure component. I’ll try to give a sense of these various options below.

What It’s About: This is one of Peter’s speeches in Acts, which are numerous and distinctive enough to almost be their own genre. Peter is always giving speeches in Acts, as is just about everyone else, and they tend to be the kind of well-crafted oratory that doesn’t sound quite right coming from a fisherman from the Galilee. What sources Luke (the author of both Acts and the gospel that bears his name) might have had for these speeches is the subject of some debate, but wherever he got them, these speeches make Peter look pretty good.

What It’s Really About: This is a bit of first-century kerygma. This is a very early proclamation about the meaning and identity of Jesus, which is why we’re reading it on Easter Sunday. Peter here is engaging in preaching, and he loads up this short sermon (or sermon section) with all the most important things about this guy Jesus: he lived, he preached, he died, he returned, he commanded us to spread the news. Easter is a day to distill Christianity into its essence, and that is what this passage does.

What It’s Not About: Peter’s speeches (and all speeches in Acts, really) are generally acknowledged by scholars to be a kind of literary creation. That’s not to say that they don’t reflect things that people actually said. But they are composed, by Luke’s sources or more probably by Luke himself, to reflect the kind of things someone like Peter would have said. In that way, they resemble those speeches you make up in your head after a big argument, that contain those one-liners that would put people in their place. These are idealized speeches, but that shouldn’t deter us. That idealized nature just makes them perfect for thinking about first-century kerygma about Jesus, and perfect for reading on Easter.

Maybe You Should Think About: Verses 38 and 42 have language of ordination and anointing. That’s the kind of language that was later seized on by people who wanted to claim that Jesus was not co-eternally God with God (“the father”), but was instead a lower or subordinate or later being that was sent by God. These are the kind of passages that fueled the christological controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries. The ones who came to be known as orthodox and the ones that came to be known as heretics were reading the same bible, and reading it carefully and faithfully, and it’s important to remember that.

What It’s About: This is one of the most hopeful and forward-looking parts of Isaiah, which gets pretty hopeful and forward-looking toward the end. Here, the prophet is casting a vision of God’s radical remaking of the world, both heaven and earth. A litany of human miseries will be eradicated, and the natural order will be remade. Jerusalem itself will be made new–no small promise in a time when it lay in ruins.

What It’s Really About: This part of Isaiah is inextricably linked to the aftermath of the conflict with the Babylonians, when the exile was concluding and the rebuilding of Jerusalem was in sight. It’s a passage about the hope inherent in that time, and about the belief that God was overturning the violent and death-dealing ways of the world. We read it on Easter because of that–because Easter is another time when we claim that God has been/is/will be remaking the world.

What It’s Not About: Christians have to be very, very careful not to subsume the passage’s original context–God’s saving and restorative work for Judea–to a new, Christian context. The life of Jesus did not and does not eradicate the past saving acts of God; in fact, the past saving acts of God all point to the life of Jesus, according to much of Christian theology. So any Christian proclamation that turns this passage or any like it into a description of Jesus does violence to God’s salvation. You have to proclaim both. God was saving Israel, and God was remaking the world, and God was in Jesus, reconciling the world to God’s self.

Maybe You Should Think About: We know a Jesus who walked around with the words of Isaiah on his lips. What does that tell us about Jesus? What kind of understanding would Jesus have had of God’s saving work? What would Jesus have made of a passage like this?

What It’s About: Passages like this are why I absolutely adore Paul. I love Paul when he gets into a groove, and falls into his characteristic pattern of working things out on the fly. The word I always like to use for Paul’s reasoning is elliptical; Paul circles back, in broad swoops, to an idea again and again, taking swipe after swipe at it until he gets it like he wants it. This passage is one of those; he has in mind to defend the resurrection, and he does it in cycles, each argument building on the last and each taking a slightly different direction.

What It’s Really About: Paul expected the immanent eschaton. He thought that the parousia would occur very soon, in his lifetime, and his early ethics reflected that. When the parousia was delayed, Paul had to start working out God’s plan in more detail. (See 1 Thessalonians 4, for example). Here, you can see some of the fruits of that; Paul has seen that Jesus was the “first fruits” of a larger resurrection, and that while it had begun, it was still on the way. This explains why there is still a world (or, at least, why we still live before the general resurrection); for Paul, God is working things out bit by bit.

What It’s Not About: This is not 21st century proclamation. It’s important, when we read first-century texts, not to assume that they conform to our ways of thinking, which have the benefit (or detriment) of 19 centuries of disputation and committee work. Paul’s words here might seem to be fairly orthodoxly Christian, but look closely and you’ll see evidence that he lived before Nicaea, Chalcedon, Wittenburg, or Azusa Street. Paul is a spiritual ancestor, but he lived and died in a place and a time, and he doesn’t get the benefits (such as they are) of all our long traditions. That’s what makes him so fascinating.

Maybe You Should Think About: This passage isn’t really about Jesus’ resurrection; it’s about everyone else’s. What’s in view is the question of what we, the rest of us, can expect. Paul was profoundly pastoral in this way; he was always answering the concerns of a flock. Here, he has in mind the question of what will happen to us all. So, on Easter, it might pay to return to that question. Christians today have a facile and unexamined understanding of what happens at death–we go to heaven–that would have confused and offended Paul. What is the distance between Paul’s view of resurrection and our view of it, and what accounts for that distance? It’s a good question for Easter.

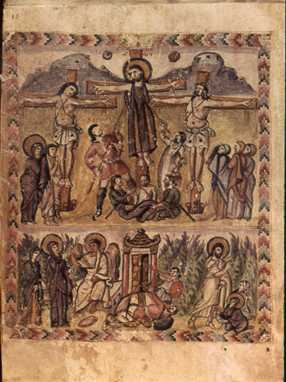

John 20:1-18 and/or Luke 24:1-12

What It’s About: The lectionary gives you two options for the scene on Easter morning: John’s longer, distinctive account, or Luke’s shorter account that has more in common with the other gospels. I prefer John, but your mileage may vary. I like the poignant details: the footrace in verse 4, the arrangement of the linen wrappings, the odd line from Jesus about holding on to him in verse 17. John’s account, to me, has the character of a fondly treasured story, with the strange peculiarity of a first-hand account. (We’ve all heard stories of someone who can remember the way the sky looked on 9/11, or the song that played on the radio on their first date, and so forth). Scholars have long supposed that the synoptic gospels are more historical than John, but that’s starting to be questioned, and I’m one that thinks that the John tradition might just preserve more history–or at least memory–than we give it credit for.

What It’s Really About: This is the core of the Christian message. This is what Christians hung their hats on–what Peter was preaching about in Acts and what Paul viewed as the moment that changed everything. The resurrection is what made Jesus Jesus, and it’s remarkable that it goes un-narrated in the gospels. We just get the aftermath. We just see the effect it has on those around Jesus. It’s an aporia in the story, but it’s an incredibly effective one. If the gospels narrated the part between Friday and Sunday, it would be corny, unconvincing, and silly. But they leave it out, and instead show the way Mary was astonished, the way the disciple Jesus loved ran, and the way Peter noticed the way the linen wrappings were lying.

What It’s Not About: It’s also remarkable what else was left out: theology. The gospels resist the urge (or, do not yet know the urge) to tell us what it all means, at least in this moment. They show; they don’t tell. Here is the power of the Easter message. It doesn’t need to be explained, at least not at first. It is just lived, and those who have lived it are generally convinced.

Maybe You Should Think About: Perhaps we should take the gospels’ cue, and show, and don’t tell. Easter feels like an opportunity to squeeze 52 weeks of church into one, since there are people who show up that day and no other day (save Christmas). But don’t let the sermon be a theological treatise. Tell stories of resurrection. Talk about how the linens looked and how you tried to hold on. Don’t describe the resurrection; describe the effect it has on people. Show, don’t tell.