Acts 2:1-21 and/or Genesis 11:1-9

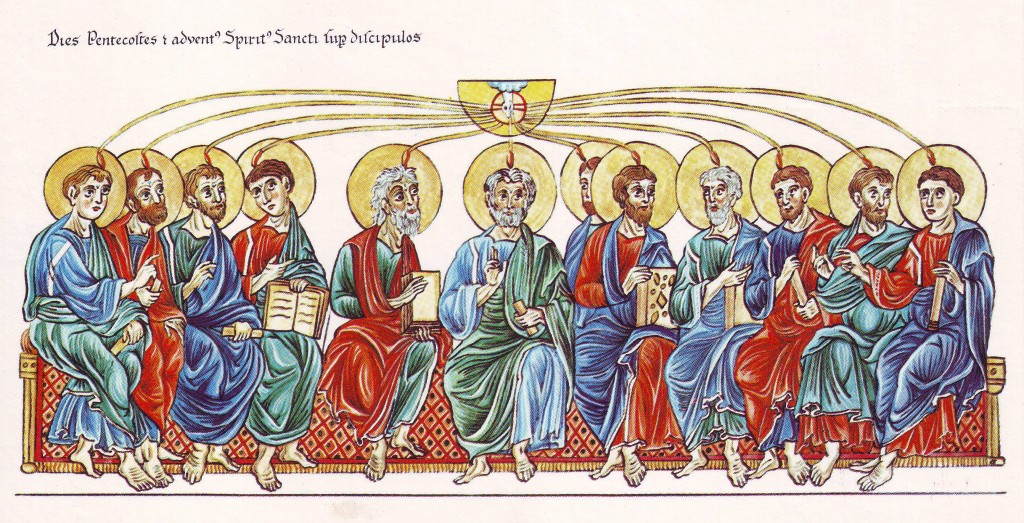

What It’s About: The common thread through these two passages is language. In the Genesis text, we have the story of the tower of Babel, in which human hubris leads to an assault on heaven and on God. As a consequence, God scatters the people, confused their language, and removed the threat–which in the context of the narrative, God seemed to be taking seriously. This story serves as a kind of etiology for the variety of human culture: it is a sign of fallenness and divine retribution, and is itself not a good thing. In the Acts text, we have a kind of reversal of this moment. This is the Pentecost text, in which the early Christian community is confronted with the arrival and presence of the Holy Spirit. One consequence of this advent of the Spirit was that the barriers of language were erased; suddenly people could communicate across barriers of speech. This is a reversal of the Babel story, and here too the variety of human culture is a mark of fallenness to be overcome. The lectionary gives the option of reading one of these stories or the other, but they really go together. In one story, we have the tale of human ambition meeting with divine retribution; in the other, we have the story of human division being overcome by divine initiative.

What It’s Really About: Both of these stories treat diversity like a problem. They both assume that unity (of language) is the ideal, and they understand the falling-away from that to be a sign of divine disapproval. In Genesis, God seems to be legitimately concerned about the growing power of the humans, and sows confusion among them as a way to sow discord. It works, and humans leave off their ambitious tower to heaven. In Acts, the view of diversity is a bit brighter, but it is still one that has human difference as a thing that needs to be overcome. The Spirit is the thing that does that; when people experience the Spirit, the old Babel-induced differences are gone. This story from Acts, then, is really a story about the erasure of difference–or the overcoming of it–as a sign of divine presence.

On the heels of last week’s “that they may all be one” prayer from John 17, this focus on unity and its source in divine presence is interesting. The Christian tradition has been self-evidently not-one; there is very little unity among Christians, nor has there ever been. These two biblical passages present two moments of human unity: an episode of humanity being unified by hubris and a common language, and an episode of humans being unified by God’s Spirit.

What It’s Not About: The story of Pentecost in Acts 2 is not a story of facile unity. It is not as if the Spirit showed up, unified everyone, and called it a day. It is not, as it has been treated so frequently in Christian history, an originary moment to which the church ought to strive to return. It is not even “the birthday of the church,” although many (including myself) have called it that. We shouldn’t think of this as a moment in history that could be returned to. Instead, this episode is a kind of narrative vision–almost an apocalyptic inbreaking–meant to point the way to a future that does not yet exist. If viewed as a brief moment of unity in the history of the church, then it is an unattainable and lost ideal. But when viewed as a vision of a future that is still in the making, Acts 2 is a promise. It is a message from another time, when people are unified across difference in the light of the Spirit. Acts 2, then, is not a lost moment when the church was perfect; it is, as Peter declares, a vision of the last days–the days when the Spirit will be poured out on all flesh.

Maybe You Should Think About: Why is language the vessel of unity and disunity in these stories? What is it about language that has the power to define us and our relationships? Both of these stories give a great deal of power to language; even God sees it as a tool that the humans can use to assail heaven. But common language clearly doesn’t bring common purpose; people with the same language can be in disunity just as much as people with different languages. So why does language end up being a metaphor in these stories? Is it standing in for something else–tribalism, factionalism, disparate creeds, or simply the estrangement inherent in human being?

Romans 8:14-17 or Acts 2:1-21 (see above)

What It’s About: Here we have more association of the Spirit with identity, with language, and with eschatology. The Romans text is part of a longer movement, taking up most of chapter 8, in which Paul is riffing on Spirit and its expressions in life. Spirit is about identity; it is the way in which we are children of God. Spirit is about language; it is the means by which we are able to cry “Abba, Father” (verses 15-16). And Spirit is connected to eschatology; it is in the groaning of creation and of God’s children (verses 22 and 23). The lectionary gives the option to use this text or the Acts 2 text (see above); together they make a powerful commentary on the workings of the Spirit.

What It’s Really About: Why, exactly, Paul wrote Romans is the subject of a lot of debate. I’m among those who think that Paul is writing a letter of introduction for himself, because he knows that the Roman church has heard rumors about him and is suspicious of him, but also because he wants their help getting on to Spain. So I tend to think that whatever Paul is up to in this chapter, he’s doing it for one of those reasons. He either thinks that the Romans think he is unorthodox with regard to Spirit, and he wants to explain himself, or he wants to talk about the Spirit as a way of leveraging his own missionary identity so that the Romans will help him. My hunch is that it’s the latter; he is laying the groundwork for why the time is ripe for him to move on to Spain (to the end of the world, as far as the Romans were concerned) and finish the work God called him to do. I think he’s telling the end of the Pentecost story, in other words. Paul is making a case that the work that began in the Spirit at Pentecost (which, granted, he does not mention and shows no signs of knowing about) can be completed in Spain. Paul has a very geographically-based understanding of salvation, and at times he seems to think that if he simply visits all the provinces and plants a church there, his work will be done and the end will come. Spain is last on the list, and the Romans are on the way to Spain.

What It’s Not About: This is not part of Paul’s systematic theology. It is a mistake (frequently made by Christians) to think that Paul, when writing about something, means it to be a part of some larger systematic whole. Paul was writing letters, not systematic theology, and so when he talked about the Spirit, it was for a purpose. He was never idly musing. That just wasn’t what he was up to. So whatever the context for these verses, you can bet that Paul had some strong purpose in writing them.

Maybe You Should Think About: Pentecost is a lot about unity, and I’ve already talked a lot about unity in the sections above. Verse 14 of this passage is an interesting commentary on unity, isn’t it? “For all who are led by the Spirit of God are children of God.” That’s a bold claim, and one that can be a real boon to ecumenical and interfaith efforts. Discerning the workings of the Spirit is the trick, of course; not everyone will grant that the Spirit leads those that they consider enemies. But if we take seriously others’ claims that they are animated by God’s presence and God’s spirit, then this verse is an admonition to cooperation. And, as a bonus, that is probably exactly how Paul meant it; there is no exegetical trickery here. Paul was writing across a great distance and across different strands of the Christian tradition; he was writing to churches (at least 5 that he mentions) in Rome that he didn’t found and over which he had no authority. So when he talks about the Spirit as the marker of unity, he means it. He was engaging in a kind of ecumenical dialogue in Romans, and being led by the Spirit was what he thought he had in common with his Roman counterparts.

What It’s About: This post is here on the day of Pentecost because it’s the place of the gospel of John where Jesus introduces the idea of the Spirit–also called the Advocate in John–as a continuation of God’s presence after his departure. This passage is a little bit didactic–I kind of imagine Jesus drawing a chart in the background as he gives this speech–but it is nevertheless on the subject of the Spirit, which is why it’s here. John knows two words for the Spirit; Spirit itself, and Advocate (or Paraclete), which comes from a Greek word for advocate, in the sense of an attorney or some other such accompaniment. It is a robust word, Paraclete–and John seems to mean it in robust ways.

What It’s Really About: This passage is from the beginning of the “farewell discourse,” the extended speech Jesus gives to his disciples following the last supper but before his crucifixion. In it, Jesus is preoccupied with what will happen after he is gone; he is comforting his disciples and trying to give a sense of how the movement will continue. This passage is part of that, addressing the ongoing presence of God among the disciples when Jesus himself has gone away.

What It’s Not About: Gospels are more like systematic theology than Paul’s letters are, but this is still nowhere near a complete pneumatology. The author of John isn’t trying to tell us who the Spirit is here, and neither is Jesus; this is simply the thing Jesus told his followers as he was facing his own death. So this is about the continuation of a movement, not about trinitarian workings or divine natures. Exegetes and theologians often squeeze stuff like this, trying to get blood from the stone, but it’s sometimes best to read it for what it is: Jesus trying to reassure and comfort his followers, and telling them that they will not be left alone. Which isn’t a bad pneumatology, come to think of it.

Maybe You Should Think About: In my opinion, the day of Pentecost is best celebrated in broad strokes. The Spirit doesn’t lend itself to being pinned down, and neither does talk about the Spirit. This probably isn’t the day to do fine-grained theology; it’s better to get caught up in the thrill and the celebration, like the Christians in Acts 2. This passage from John, then, tells us one big truth: that God doesn’t die with Jesus, and that God is with us even when Jesus isn’t anymore. That’s enough of a pneumatology to get out of this passage.