Jeremiah 2:4-13, Sirach 10:12-18, or Proverbs 25:6-7

What It’s About: Jeremiah and Sirach are both about God’s anger at the Israelites for forsaking their special covenantal relationship with God. Jeremiah’s invective is particularly strong; he recounts a version of the exodus story, reciting the salvation history of the Israelites under God’s direction, and then proceeds to condemn them and “accuse your children’s children.” Sirach, likewise, is all about the relationship of God to God’s people, and the terrible power of God to punish those who abandon God. The Proverbs text is really something different altogether, and it goes much better with the story in Luke below than it does with its companion texts here. It’s a bit of practical advice: don’t show off how amazing you are, let others figure it out first.

What It’s Really About: The Jeremiah and Sirach texts are embedded in a couple of the deepest bedrocks of the Hebrew Bible. One is that God and the Israelite people are bound in covenant with one another, and that the breaking of that covenant is an utterly disruptive and untenable thing. The other is what is often called the Deuteronomistic world view, which is found in Deuteronomy but also throughout the Hebrew Bible, and which says basically that people get what are coming to them. The “I accuse your children’s children” thing is a great example of this; in the Deuteronomistic perspective, guilt (and blessing) is strongly correlated with behavior, and it can even be passed down generationally. In the Jeremiah text, God is speaking (through the prophet) directly about the experience of having been abandoned by the people. God is actually a little flabbergasted by this; “have you ever heard of such a thing” is a pretty good synopsis of verses 10-13. In the Sirach text meanwhile, the interest is more in cataloging what happens when people ignore or rebuke God. “Nice little nation you got there. Be a shame if something happened to it.”

What It’s Not About: Jeremiah 2:11 is interesting. It claims, even as it complains about the Israelites fleeing to other gods, that the other gods aren’t real. This is a developing thread throughout the Hebrew Bible. You can see evidence of a polytheistic (belief in many gods) world view, a henotheistic (belief in the existence of many gods but the worship of one) world view, and a monotheistic (belief in and worship of one god) world view. Jeremiah here seems to be straddling henotheism and monotheism. Much like when Paul talks about food sacrificed to idols in the New Testament, there is a sense here that other gods are dangerous even as the text asserts that they do not really exist. It’s not the actual being of rival deities that is troublesome; it’s the distraction from the one true God. There are places in the Hebrew Bible where the other gods do seem to be really real–just weaker and subordinate to God. But here you see the beginnings of the claim, which will come to dominate and characterize Judaism and Christianity, that there is only one God. Nevertheless, idolatry is bad, even though the other gods aren’t really real, because it robs God of loyalty and worship.

Maybe You Should Think About: Jeremiah represents something close enough to our own ways of thinking that we can recognize it, but not so close that it feels like a natural fit with our modern world view. There’s the incipient monotheism, the notion of propriety of worship, and so on. But there’s also this hereditary sense of guilt and the notion that gods belong to particular nations. Attitudes toward and about God change over time. How do we read texts like this and “translate” for our own contexts today?

What It’s About: Near the end of both letters and sermons, the writers/preachers tend to pile up exhortations in an attempt to drive home the point. Or else they load up the end with things they hope you’ve already heard in the beginning parts, to reiterate what you are already thinking. There is some debate over whether Hebrews is a sermon or a letter (I think it’s a sermon), but either way that’s what is going on in these verses. It’s near the end of the book, and the writer/speaker is deep into exhortation territory here, throwing out a list of things that he (or she) wants the hearers or readers to remember. It’s a laundry list of good, ethical advice and pushes toward faithfulness.

What It’s Really About: It’s interesting what makes it onto this list. Not very much of it is immediately connected with the material that has come before it (that the lectionary has been working through for weeks now). These are more general exhortations than they are recapitulations of earlier material. Be hospitable, remember people who are in prison, remember those who are being tortured, honor marriage, don’t love money, do good. These are solid ethical calls; there’s nothing really controversial here. It’s a call to be good.

What It’s Not About: This doesn’t really sum up or recapitulate the earlier parts of the book. The most recent parts of Hebrews have been about heroes of the faith, the role of Jesus as divine/human intermediary, the meaning of faith, etc. This stuff is very general. We’re left to wonder why. Was this a standard way to end a sermon? Was this stuff added to make the ending more powerful? Something else?

Maybe You Should Think About: This list is someone’s last word on what a Christian life ought to entail. Whether it’s a letter or a sermon, this section is the author’s final words on how we should act, conduct ourselves, consider others, etc. And it’s surprisingly basic stuff! Be good, basically. Do the stuff you already know!

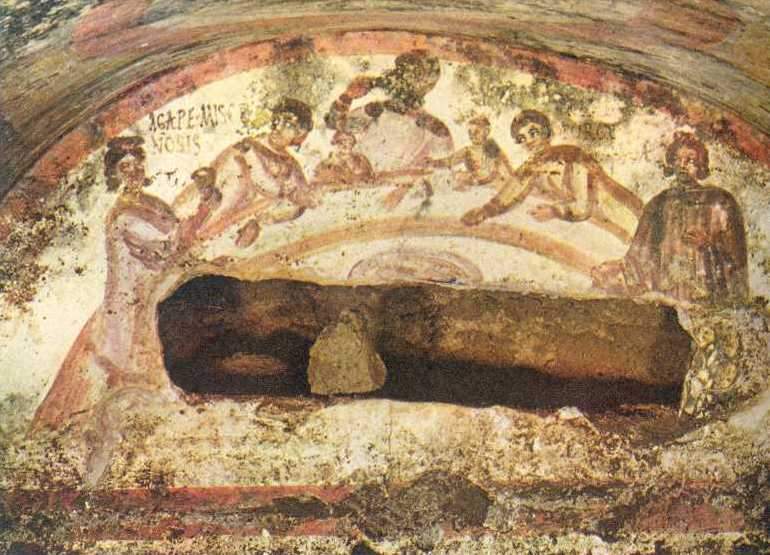

What It’s About: This is a parable of Jesus, about pride of place and the dangers of thinking too highly of yourself. It echoes the Proverbs text above. Here, Jesus is describing a dinner party, and suggesting that you humbly seat yourself in a less-good spot, in hopes that you will be asked to move up to the more honored places. Much better than starting at the honored spots and being asked to move down.

What It’s Really About: This is really two semi-parables rolled into one. At the same dinner party where people are being demoted and promoted from and to places of honor, there is an admonition (in verses 13 and 14) to invite those who cannot repay you. The poor and downcast cannot repay you with their own invitation, which makes you magnanimous in your generosity. All of this trades on the systems of honor and shame in antiquity; Jesus is giving advice on the best way to negotiate social honor. But he’s also critiquing the honor system itself, and pointing out that the best way to “win” the game is to show generosity to those who can’t repay you, so that your honor will be for everyone’s benefit but your own. Pretty sneaky.

What It’s Not About: Notice how this parable begins: with a real dinner that Jesus attended. The first bit isn’t parable, but an actual meal, at the home of a Pharisee, on the sabbath. This should tell us that most of our ideas about Pharisees are not very accurate. Jesus had far more in common with Pharisees than he had disagreements with them! They dined together on the sabbath! Sometimes we argue most strongly with those we are closest to (think about political discussions with your uncle at Thanksgiving), and that’s what is going on with Jesus and the Pharisees most of the time.

Maybe You Should Think About: What’s at stake in this parable? Is it really about our own honor, and how to preserve it and increase it? Or could it be about something else?