Antonio Perez-Ramos argues in his contribution to the Cambridge Companion to Bacon that while Bacon’s method has been severely criticized, Bacon’s program of human improvement through scientific and technological progress has not been, until the early part of the 20th century (he references Hans Jonas, Adorno and Horkheimer as skeptics of Baconism): “Bacon’s insight that scientific knowledge is the main guide through the turmoil of history and of Nature and that science effectively can (and should) beget the reconciliation of man with himself and with the outside world became an anthropological certainty of European mankind relatively soon.”

At the center of Bacon’s program is the idea of a “good” science, that is, that scientific advance is a good in itself: “For Bacon science is itself a moral good which has to be integrated into the fabric of society as a whole, though the ambivalence of the technocratic form of culture that lurks behind this aspiration is not clearly understood or unveiled.”

Bacon’s use of gunpowder as an example of advancement “makes it possible to construe Bacon’s insight as a decisive step in the gradual perception of the self-acting potentialities of technology; so science becomes autotelic.” The only check on scientific progress is the self-policing of scientific research itself – the possibility that later research will falsify earlier: “in good Baconian doctrine a science which led to the improvement of artillery or to the invention of artificial means of preserving good was equally good, because it was equally useful for the end required, that is, a purely technical challenge that research had proposed to meet. Hence ‘good’ science is not the antonym of ‘bad science’ but of useless or rather idle knowledge.”

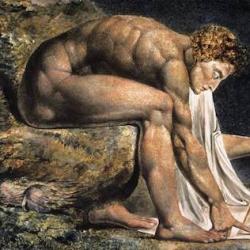

Whatever his intentions, Bacon contributes to the “disenchantment ( Entzauberung ) of the world with which Max Weber vividly characterized European culture in the modern age has been expressed in a plurality of fields. One of them was religious reform but not less significant in the domain of cognitive goals was the victorious image of Nature as a soulless mechanism, a vast storehouse or an insensitive witness to be cross-questioned in the most severe fashion . . . . Bacon’s program is perhaps nowhere better depicted than in the forensic image of the stern judge who dictates his questions in order to extract manipulative directions with regard to his sole practical interests.”