In her study of Tudor-Stuart notions of metaphor (Translating Investments), Judith Anderson explores the significance of nominal sentences – sentences without verbs, much used in ancient languages but rare in English.

Does a nominal sentence imply a copulative verb of being? Or is it expressing some other sort of relation between subject and predicate? Anderson describes various answers to these questions, and offers this summary of Ernst Cassirer:

“Intent on the Kantian rationality of the copula, he agrees with [Emile] Benveniste that the apparent copula of the nominal sentence is only apparent but disagrees with the linguist’s sense of the formal (grammatical) timelessness, impersonality, and essentiality of such sentences. To the contrary, the missing copula in the nominal sentence ‘’is not a universal term, serving to express relation as such, but . . . designates existence in this or that place, a being-here or being-there, or else an existence in this or that moment. . . . Formal ‘being’ and the formal meaning of relation are replaced . . . [in the nominal sentence] by more or less materially conceived terms which still bear the coloration of a particular sensuously given reality’” (40-1).

The underlying meaning of the copula as “to exist” or “to occur in reality” stands out, but in Cassirer’s view (and words) “comes ultimately to be so permeated with the relational [that it becomes] the sensuous vehicle of a pure ideal signification.” Anderson notes that this formulation joins “the material and formal, the existential and essential, and the sensuous and ‘spiritual’” in a relation of reciprocal determination. Echoing Hamann, Cassirer says that “language shows itself to be at once a sensuous and an intellectual form of expression” (41).

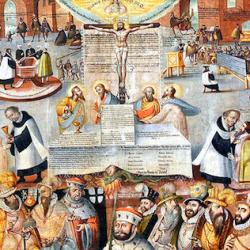

This exploration of nominal sentences occurs in a discussion of Reformation-era sacramental theology, and the implied semiotics in the debates between Luther and Zwingli. She observes, for instance, Zwingli’s interpretation of the “est” of the words of institution arose from a “seminal insight into the metaphoricity inherent in the verb of being” (44). There were other options: The original Greek words of institution, after all, did not contain any equivalent to est; in Greek “this is my body” is a nominal sentence. Some (she cites Oecolampadius) worked from the verbless Greek text and thus concluded that the trope in the words of institution was located not in est but in corpus. Body, not being, was metaphorical.

Calvin provides another option that accords with Cassirer’s both/and of sensuous and ideal: “In Reformation terms . . . the reciprocal determination he describes might be approximated to, or recognized as a translation of, something between the substantive verb of real presence and the figurative verb of absence, and thus between the extremes of Luther and Zwingli. This is the middle ground eventually occupied by Calvin” (41).

She concludes that “The eucharistic debates of the earlier half (roughly) of the sixteenth century constitute an epistemological watershed between the earlier age and the one to come. Alone, they hardly cause this overdetermined cultural crisis, but even aside from their contribution to its content, they critically organize and crucially express it” (48).

An intended Reformation indeed: Eucharistic debates contributed to a shift in the basic epistemological and ontological assumptions of many Europeans, a shift in what it means to be and to know what is.