Jimena Canales has written a history of A Tenth of a Second. It seems an arbitrary cut-off. Why not 1/100 or 1/1000?

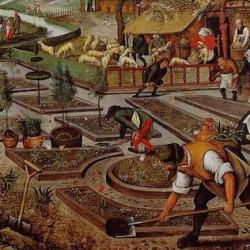

After all, we’ve been able to measure in finer units than 1/10 of a second: “In 1878 Eadweard Muybridge famously photographed running horses galloping in a manner never seen before, seizing them in a 1/500th of a second by using multiple cameras. In 1882, single-lens photographs made by the French physiologist Étienne Jules Marey surpassed this limit. By 1918, Lucien Bull, the last assistant to Marey, was able to photograph fifty thousand images in one second. In the 1930s, Harold Edgerton’s stroboscopic images produced at MIT captured images in the span of a 1/3,000th of a second. Today, millions of frames per second can be recorded” (3).

Yet, the 1/10 interval recurs in human life with puzzling regularity: “Tie a piece of coal to one end of a string and twirl it rapidly. If the coal makes a complete turn in less than a tenth of a second, it will seem to form a closed circle. Slow down its speed and the closed circle disappears. Try this experiment with a cinematographic projector. If successive frames pass at a speed exceeding the tenth of a second, the illusion of movement appears smoothly. Reduce its speed, and the illusion disappears. Look closely at a rapidly moving target and try to time the precise moment when it crosses a specific point. Compare the moment with somebody else’s and you will see that each of your determinations will probably differ by a few tenths of a second. Step on the brake of your car when an obstacle appears in front of you, and despite your best efforts, a lag time, close to a tenth of a second, will haunt your reactions. Try to read as many words as you can in ten seconds, and you will notice that the number is about a hundred: one word every tenth of a second. Time yourself while talking, and you will see that the time needed to pronounce each syllable will never be less than a tenth of a second. Analyze the electrical rhythm of your brain, which, when at rest, will average ten cycles per second. Study a ‘perceptual moment’ and find that it lasts about this same amount” (3).

Canales is particularly interested in the relation between the microtime of 1/10 of a second and the macrotime we call modernity, particularly as modernity took shape in the late nineteenth century. Descartes had taught that stimulus and response were simultaneous. Experiments proved him wrong. There was a lag time, and that lag time held enormous implications for how we understand cognition and our engagement with the world: “Increased attention to the tenth of a second illustrated a growing concern with the temporality of cognition. Historians and philosophers have frequently focused on how, since antiquity, the intellect was modeled as a camera or mirror. Yet from early modern times onward models of cognition slowly started to shed Cartesian, static metaphors and became instead modeled after temporal ones. By the middle of the nineteenth century the temporality of cognition was widely recognized” (9).